India family offices: Tech exposure

Demand for technology exposure among India’s most affluent is intensifying. Family offices may vary in profile, experience, and mode of access, but they all want a piece of the latest hot start-up

Aarin Capital, a venture capital firm backed by proprietary capital from Infosys alumnus T.V. Mohandas Pai and Manipal Group's Ranjan Pai, committed $9 million to Byju's in 2013. The online education platform has since emerged as India's most valuable start-up, hitting $16.5 billion on closing its latest round in June. Aarin is sitting on a paper gain of more than 750x.

It is a remarkable return for a family office, yet Aarin ranks low in the Byju's cap table. Subsequent rounds have seen the likes of Sequoia Capital India, Tiger Global Management, General Atlantic, Silver Lake, The Blackstone Group, and BlackRock bet big on the start-up. This evolutionary path is a familiar one. Pick any Indian unicorn and the bulk of the capital will come from offshore funds backed by international LPs.

In 2019, domestic investors accounted for 26% of all funding raised by Indian start-ups, according to a report by 256 Network, which promotes GP-LP engagement on India, and Praxis Global Alliance. This compares to 30% in Korea, 57% in China, and 84% in Japan. It is a fair reflection of the institutional investor landscape. Private equity is largely off-limits to India's larger, regulated players, so the onus falls on high net worth individuals (HNWIs) and ultra HNWIs operating at the margins.

But the report also makes a bold prediction: Indian UHNWIs will be responsible for 30% of the $100 billion that Indian start-ups are expected to raise by 2025. This will come on the back of a surge in technology sector investment, with the country's 56-strong crop of unicorns set to swell to 150.

"Over the last 18 months, that 26% figure has changed dramatically," says Dhruv Sehra, founder of 256 Network and previously an investment professional at Kalaari Capital. "A lot of the capital going into Indian start-ups is from India because people see monetary results. They are testing the water with early-stage capital, and in two or three years there will be more growth-stage capital. Many GPs are already raising growth-stage capital from Indian LPs to support the winners in their portfolios."

Money, meet opportunity

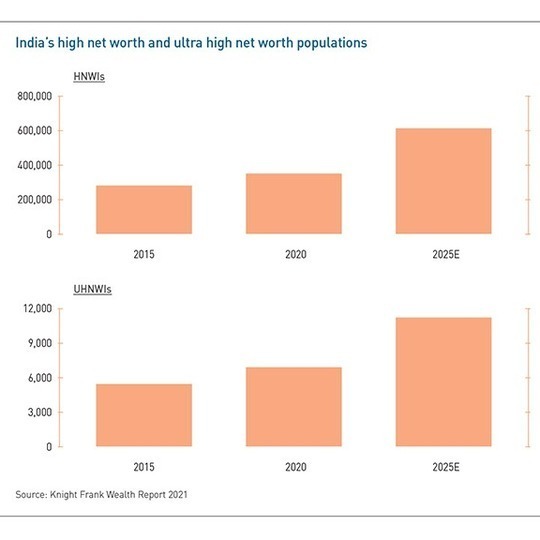

There is no shortage of emerging wealth in India. The country is home to approximately 350,000 HNWIs – defined as those with over $1 million in assets, including primary residence – according to a real estate consultancy Knight Frank. Moving up a level, India has around 6,900 HNWIs with $30 million-plus in assets. By 2025, these figures will be 611,500 and 11,200, respectively. The growth rates between 2020 and 2025 will outstrip those of every other Asian market apart from Indonesia.

At the same time, there are abundant perceived opportunities in technology. The emergence of domestic IPOs as a liquidity channel for unprofitable start-ups – a consequence of investor demand and regulatory adjustment – and the strong performance by these companies coming out of COVID-19 has prompted a surge in investment activity.

Last month, Kotak Investment Advisors achieved a first close of INR13.9 billion ($186.7 million) on its pre-IPO vehicle, surpassing the initial target of INR10 billion in three months. The firm, which caters to clients with more than $1 million in investable assets, has been active in the unlisted space for three or four years, educating investors and advisors on the potential of technology-enabled businesses.

"We would explain how we saw the same categories unfold in the US and China, but most of the equivalent companies in India were not mature enough to list. There wasn't a late-stage playground for investors," says Srikanth Subramanian, Kotak's CEO for private wealth investment advisory. "In the past year, more companies are getting ready to list, so the next 5-6 years will be interesting. They have the potential to change the index composition because many will achieve robust valuations."

Mapping the HNWI and family office landscape – and the different routes into technology – is complicated by the diversity of the participants. 256 Network and Praxis estimate there are more than 140 family offices catering to Indian UHNWIs, of which half have formal structures.

Aarin would fall into the business leader family office category, alongside Azim Premji's Premji Invest, Rishabh Mariwala's Sharrp Ventures, and Rata Tata's RNT Associates. Technology entrepreneurs such as Ritesh Agarwal of Oyo (Aroa Ventures), Kunal Bahl of Snapdeal (Titan Capital), Sachin Bansal of Flipkart (Navi), and Rajul Garg of Pine Labs (Leo Capital) form another category.

Still more family offices are backed by various non-resident Indians and celebrities. The latter tend to be film stars (Amitabh Bachchan, Deepika Padukone) and cricketers (Sachin Tendulkar, Virat Kohli).

Flipkart onwards

Rohan Paranjpey, an executive director for alternative investments at Waterfield Advisors, a multi-family office, highlights Flipkart achieving unicorn status as a watershed moment for family offices and technology. Some had made commitments to venture capital funds in the preceding few years, but the rise of Flipkart – and the returns created for angel investors – pushed the strategy into the mainstream. That was 2012, and interest has intensified over the ensuing years.

"Since 2015, we've seen more direct investments into large tech companies by virtue of the purchase of shares from existing employees," says Paranjpey.

"Whenever these companies give liquidity to ESOP [employee stock ownership plan] holders, they work with wealth managers in India because they think they can get better value than in the institutional market. When institutions buy secondary shares, they normally want a discount. And then these are non-preferred shares, they don't come with any rights."

These sentiments are echoed by other industry participants. Where once multi-family office operators would proactively scout for deals in their networks, now there is more inbound deal flow. Munish Randev, founder and CEO of Cervin Family Office, another multi-family office, typically sources opportunities from founders who reach out directly, investment banks running rounds, early-stage venture capital funds, and crowdfunding and angel platforms.

He offers two reasons for the growing acceptance of family offices as a capital partner. First, start-up founders have realized they can no longer be accountable only to funds; they see the value of potentially longer-term capital. Second, some family offices bring domain expertise and networks that can benefit start-ups. This might involve a family with a consumer goods background making industry introductions or a celebrity promoting a brand on social media.

"Funds reach out to us when they hit their exposure caps, need external capital, but want to keep the process closed," Randev adds. "They also provide co-investments to family offices. These are not top-up funds. We come in on the same terms and invest directly into the portfolio company, so the family office appears in the cap table."

How a family office chooses to participate in the technology sector is a function of its sophistication and experience. Early movers started off with early-stage direct investments, suffered because of adverse selection, so switched to relying on VC funds to get access to the best deals and looking to co-invest alongside these managers. Other family offices have viewed the asset class from afar, reluctant to invest given their lack of industry knowledge and sourcing networks.

Both investor types are targets for Waterfield's fund-of-funds. It seems a contrarian bet, given historical sensitivity around cost and control: going through one fund to access others involves paying a second layer of fees and offers less transparency regarding deal flow and exit outlook. But Waterfield believes it is the best way to establish relationships with managers that are generally unwilling to accommodate local LPs.

"We want to make Indian capital as attractive to high-quality funds as international capital. We can collect capital across family offices and become a large institutional LP, which may also give us access to the best co-investments," Paranjpey says. "There are funds that are heavily oversubscribed and had never previously thought about raising from domestic family offices before making room for us."

Even family offices that do have direct access to deal flow may opt for an outsourcing arrangement, which could mean handing over complete discretion through a fund-of-funds or relying on third-party advisors with strong due diligence capabilities. For example, technology entrepreneurs and large family offices that invest directly and through funds have tasked Cervin to work on risk management – tracking exposure and performance across different stages, sectors, and companies.

Multi-family offices have also been recruited to slice and dice deals. One family might be leading an investment, wants to bring in other family offices as co-investors, but it is reluctant to ask directly, so the multi-family office effectively runs an informal process.

Time to lead?

It remains to be seen whether the HNWI and UNWHI segment becomes significant enough to lead funding rounds on regular basis. Start-ups – and earlier investors – often prefer to have a VC in this role because it represents an endorsement for other investors. As a result, due diligence might be confirmatory rather than exploratory and there is greater confidence that pricing methodologies and deal terms meet industry standards.

To 256 Network's Sehra, though, it is a matter of time before some – but not all – family offices step up. "Family Offices typically go through at least one capital cycle before jumping in with both feet," he says. "Today family offices will lead rounds because it is of strategic benefit to their existing business, especially of a company which has proven its utility. But if they are doing it from a purely returns perspective, they are still quite cautious."

Various forces could undermine the technology ambitions of India's family offices. Adverse selection is one, depending on the mode of access. In the past, these investors have been brought in to prop up troubled companies, leading to subpar returns. A repeat of this would dent confidence.

Moreover, there are concerns about behavior within the multi-family office community, with providers accused of taking placement fees from founders or funds looking to raise capital, while simultaneously receiving fees from family clients for advice on investments. The regulator stepped in last year to draw a line between distributors and advisors, but some industry participants work around this by excluding private markets from advisory mandates.

But increased domestic exposure to start-ups is also described as an irrevocable trend. HNWI demand for Zomato's INR93.7 billion IPO last month coursed from the pre-listing placement into the secondary market and is now being felt in the growth-stage rounds for other start-ups. The private markets portion might still be relatively small compared to contributions from foreign institutional investors, but it is being driven upwards by the exuberance of youth.

Rahul Chandra, a partner at Arkam Ventures, points to changes in India's retail investor base, with much of the demand for new brokerage accounts coming from millennials who are consumers of technology and want to invest in it. Similarly, within family offices, the younger generations are assuming influential roles, often after being educated overseas.

"They come back from the US, and they want to have exposure to technology. They are comfortable with the notion that a company is loss-making, but ultimately the network effect and the power of the market share will start showing," Chandra says. "That second generation is spending more time managing wealth and directing capital into tech stocks, private and public."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.