Australia LPs: Revert to the mean

Engagement, efficiency, and accountability are the driving forces behind reforms to Australia’s superannuation system. But could private equity lose out in a race to the middle on returns?

Strong private equity returns are giving Australian superannuation funds some breathing room. "Trustees are saying, ‘Maybe you're overallocated, maybe you have outflows, maybe the allocation isn't what we need for the long-term – but the numbers have been so great, let's not do anything to jeopardize that in the short-term until we figure out what we want to do,'" one portfolio manager explains. "We have a hall pass, at least for this year."

AustralianSuper, the local behemoth with A$225 billion ($170 billion) in assets, was unequivocal in linking a record single-year return for its balanced option to a long-term outlook and "a higher allocation to growth assets such as listed shares and private equity." Its PE portfolio has doubled in size to A$9.6 billion since 2018, and the 40% uptick in value for the 12 months ended June comfortably beat public equities. There's a desire to push the overall allocation from 4.2% to 10%.

AustralianSuper's approach to PE is no secret. For the most part, it runs a highly concentrated portfolio, making fund commitments of $300 million-plus to international managers. There is a strong appetite for co-investment – usually, but not exclusively with portfolio GPs – and often in a co-sponsor role. The twin objectives are to access high-quality assets while reducing costs: zero-fee co-investment brings down the overall cost of the relationship.

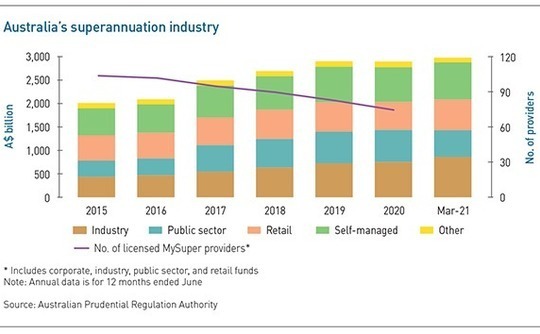

Almost every superannuation with a meaningful private equity program is pursuing more co-investment as a means of fee mitigation. AustralianSuper, given its size, arguably offers a snapshot of behavior after the current wave of consolidation. Various combinations are being mooted or actively discussed. First State Super and VicSuper have already joined forces to become Aware Super, the second-largest player with $126 billion in assets. SunSuper and QSuper will surpass that with A$200 billion.

But the journey will be far from smooth, and the destination is unclear. Rather than big beasts making their presence felt in global private equity – not an unrealistic ambition for the world's fourth-largest pension market – it might end with allocators rendered toothless by a fear of failure.

Conflicting objectives sit at the heart of the issue. For government, consolidation is the byproduct of a drive for greater efficiency and accountability within the superannuation system. While the latest reforms should deliver this, concerns are rife about collateral damage. On one hand, it is feared that performance benchmarking will deliver homogenous returns rather than the best risk-return outcomes. On the other, a potentially fraught disclosure regime may restrict access to top GPs.

Mapping the future

Even as robust returns grant portfolio managers temporary respite from the pressures of a fee-sensitive system that is allergic to high-cost asset classes like private equity, they are thinking about the implications of Australia's Your Future, Your Super legislation.

Some senior executives have already made their views clear. "This will likely push funds towards more passive investing and more fee-efficient and low tracking-error positions, which may cut out some really high-performing sources of returns for members," Kate Farrar, CEO of LGIAsuper, which will have A$20 billion in assets on merging with Energy Super, told Global Investment Institute.

Others prefer to keep their counsel, noting that performance benchmarking – which Farrar believes will encourage superfunds merely to track these marks – represents uncharted territory. The Australian Investment Council (AIC) is taking this approach, while putting Canberra on notice that a significant contraction in superfund appetite for private markets should prompt a reevaluation.

"If we see that eventuate, we will want to talk to government again and encourage it to look at recalibrating the reforms to deliver a better market outcome," says Yasser El-Ansary, the organization's CEO. With a nod to the highly charged atmosphere, he adds: "Any reforms to the superannuation system in Australia, modest or significant, tend to be controversial."

These observations contributed to legislation that has three key components: a stapling system, so a superannuation account follows an employee from job to job; a requirement that trustees act in the best financial interests of members at all times; and annual performance tests, with superannuation providers obliged to inform members if they fall short one year and then cease accepting new members if they fail the following year as well.

The Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) serves as the authority on performance. It analyzes the strategic asset allocation (SAA) set by each superfund and calculates a return target over a rolling eight-year period based on benchmarks established for each asset class. Private equity will be benchmarked against global listed equities – not unlike what many superannuation funds do internally. Nevertheless, there are concerns about a reversion to benchmark tracking.

"Trustees will probably develop investment strategies aligned around these rules rather than what is directly in the best interests of members. The consequences of failing the performance tests are so catastrophic," says Nathan Hodge, a partner at King & Wood Mallesons (KWM). "However, they also have to justify that what they do is in the best interests of members. It will be interesting to see how this legislation influences behavior."

This is confirmed by the portfolio manager cited earlier, who flags the threat of portfolio volatility on single-year performance. While he doesn't expect private equity allocations to fall materially, because the capacity for alpha generation is well-recognized, neither will they grow beyond the standard 3-6% range. Ultimately, the volatility risk is too great, and the notion of going into too many new funds – and the impact of the j-curve effect on near-term returns – is unpalatable.

"The best you can do is maneuver your portfolio, so it looks more like the index, and minimize exposure to things that don't match that public market profile, which means fewer funds every year, relative to the size of the program, and more secondaries and co-investment," the manager says.

"Exposure to alternatives will likely be limited. Superfunds must decide whether they want that benchmarking tracking error to be for private equity, private credit, infrastructure, or real estate. They will look at their internal capabilities for each asset class versus the benchmark and allocate more to the one with the best chance of outperformance. It is not objective portfolio construction."

The caveat is that it will take at least six months, plus some detailed modeling, to ascertain the impact of the legislation on asset allocations. Several other portfolio managers endorse this view. "We are not planning any changes right now. It is too soon to tell what action might be needed," says Serge Allaire, head of private equity at Cbus Super, which has more than A$54 billion in assets.

Agreeable benchmarks

This is one of three areas of general agreement. The other two are that, even in the medium term, larger players are unlikely to see sharp shifts in allocation because changing up a private equity portfolio is time-consuming and can be expensive; and the public market benchmark is eminently beatable, based on historical trends.

While property and infrastructure managers lobbied successfully for a dedicated unlisted benchmark, private equity held back. According to AIC's El-Ansary, this was because "there was no simple way to land on an alternative benchmark that would have broad-based support from both investors and managers and would be an appropriate bar to set." The conclusion was the industry shouldn't oppose a public market benchmark when it could offer nothing better.

Uppermost in the minds of investors in real estate and infrastructure was a belief that public market comparatives would be unfair. A portfolio largely comprising passive vehicles that own properties and collect rent represents a starkly different risk-reward scenario to listed real estate investment trusts (REITs) fed by residential real estate developers.

"A huge amount depends on the benchmark for your asset class and whether it accords with the reality of what you are investing in," says Geoff Sanders, a partner at law firm Allens. "Are you testing the same investment performance, the same cost base, and the same fee base?"

Moreover, an unlisted benchmark is acceptable to Australian investors in infrastructure, for example, because there is a relatively high degree of homogeneity in their portfolios. IFM Investors, which is owned by 26 superannuation fund shareholders and invests heavily on their behalf, is a common factor. A consensus is less likely to be reached on a private equity benchmark when programs can differ markedly in fundamental ways, such as domestic versus international exposure.

At the same time, there are readymade global private equity benchmarks, but superfunds might be reluctant to be held accountable against them. A second portfolio manager notes that Australian groups generally have less exposure to venture capital than the global norm, yet this area has outperformed in recent years. Therefore, they risk trailing a benchmark that is heavy on VC.

"If you do the math, it's easier to beat a listed benchmark than an unlisted benchmark," he adds. "I know of people within funds who were told by their strategy departments that if there were another benchmark for private equity, they would probably cut the allocation, because it's harder to beat."

Cost conundrum

The Productivity Commission report was regarded as a progression from the original MySuper reforms, which created a class of easily comparable mass-market pension products, because there was an emphasis on performance, rather than just cost. This has been carried forward into the benchmarking system, which focuses on net returns.

The enduring hope is that GPs visiting Australia with a view to fundraising will no longer find their discussions are challenged by an unfriendly policy and regulatory framework. "Introducing a test that incentivizes a focus on after-fee performance is good," says AIC's El-Ansary. "But it's about the detail and how it is implemented, not so much the concept and whether it is meritorious."

Initial feedback on the role of cost in benchmarking is muted. There is an assumed annual fee for each listed asset class, with infrastructure set at 26 basis points compared to five basis points for Australian equities. Other actively managed asset classes are likely to be treated much the same. The legislation also calls for an online YourSuper comparison tool for members, which will sit alongside APRA's existing heatmap that tracks changes in superannuation fees and costs.

At the provider level, if a fund opts for a fee structure that is higher than its peers, a best-interest advisory opinion is required. The first portfolio manager notes that advisors are wary of stating that 3% outperformance is sustainable at 30 basis points in extra cost. They would endorse a 12% return over 15%, for a lower fee, reasoning that the outcome is still likely to be better than public equities.

"I don't think fee and cost pressure will ease because of the underperformance test," adds Sanders of Allens. "The reality is funds will still be judged in other contexts based on how expensive they look. And they will still compete to attract members based on fees and cost because those are easier for people to understand than net returns."

In situations where superfunds are falling short of their overall benchmarks, more aggressive strategies – higher risk, higher return, higher cost – might be adopted to make up lost ground. However, early anecdotal evidence points to volatile behavior, especially among the smaller providers. Some are defying their advisors and sticking with lower fee options because there is greater certainty as to the return or they are familiar with the framework.

At the same time, one Australia-based fundraising professional with a global private equity firm, suggests that superannuation providers are taking on additional risk in their tactical asset allocations (TAA). The SAA – used by APRA for benchmarking – is unchanged.

"Four years ago, you wouldn't have expected to hear these funds talk about private equity. Now they are making allocations to managers in the US. When asked about the rationale, they say returns and their consultant has a view on the manager. But it doesn't form part of a strategic allocation," the fundraising professional says.

"They are tilting to play catch-up on performance, and if you have an 8% strategic allocation to private equity and a 7% tactical overweight on top of that, it will have a meaningful impact on the portfolio. But you can't build a program overnight. They could end up being hurt by the j-curve."

Big beasts

It is important to note that this phenomenon is confined to the smaller end of the market and, perhaps, to providers that the regulator expects to be victims of consolidation – because they fail the performance test and are closed to new members, or they agree to mergers before this happens. Larger players with established, diversified PE programs are better placed.

"The major private equity LPs are the larger funds. Smaller funds often don't have a traditional asset allocation. They might have gone for alpha in infrastructure or property," says the second portfolio manager. "In some cases, private equity has hurt them. And in every case, the fee burden to get into private equity is high. They don't have the scale to average down cost using co-investment."

Size is not necessarily a panacea. KWM's Hodge observes that some smaller superfunds have achieved strong performance. Similarly, there is no guarantee that larger players will be able to negotiate preferential terms in a global market where demand for access to quality managers exceeds supply, or that superfunds can build out successful co-investment programs.

But the Australian government's preferred scenario appears to be less variability in outcomes across the superannuation system; and facilitating the emergence of a core group of mega-funds that drive down the cost of implementation is a relatively straightforward means of achieving that goal. It is unclear whether private equity can play an expanded role in this vision of the future, or indeed whether it makes the bulk of members richer.

"I think it plays into the whole narrative of homogenized returns," says Michael Gallagher, head of Australia at the Alternative Investment Management Association (AIMA). "The conversation has forgotten that people can do better than the benchmark, but there is no incentivization to do more than just meet the benchmark. It's like just going out and buying market-tracking ETFs."

SIDEBAR: Disclosure - Not so indecent

Seven years ago, a well-intentioned transparency-oriented reform threatened to push relations between Australia's superannuation funds and VCs to breaking point. The much-maligned portfolio disclosure regime was repeatedly delayed and ultimately expired before passing into law. Now it is back, in modified form, and industry participants are gauging the potential impact.

"This has been a long journey and a complex one for regulators and government. It started off with a simple proposal – all superfunds should be required to disclose their investments so that mum and dad members know exactly where their hard-earned savings are being invested – that sounds very sensible and balanced," says Yasser El-Ansary, CEO of the Australian Investment Council (AIC). "But execution is difficult. There is a lot of detail, and many areas of uncertainty that have yet to be resolved."

When the issue first emerged in 2013, the government wanted superfunds to publish full details on their portfolio holdings, including relevant valuations, on a look-through basis – not only identifying the funds but also the assets that each fund is invested in. Superfund portfolio managers worried that they would be dropped by Silicon Valley venture capital firms much like various US LPs over a decade earlier.

A breakthrough in the ensuing to-and-fro came about three years ago when the government agreed that superfunds could isolate up to 5% of their portfolio by net asset value, enabling them to shield certain sensitive commercial information from public disclosure. The Your Future, Your Super legislation, which recently passed into law, removes the 5% disclosure exclusion.

"We continue to worry that forced disclosure of holdings and valuations will disadvantage the superfunds in accessing the best investments," says Rick Baker, co-founder of local VC firm Blackbird Ventures. "It seems crazy to require look-through disclosure with no materiality threshold."

However, the regime differs from previous iterations in that disclosure stops at the point where the superfund ceases to have full control over the investment. It would, for example, state that it has exposure to Blackbird's second fund, put a value on the holding, but the identities of the portfolio companies within the fund would remain outside of the public domain.

While fund-level disclosure isn't ideal in the eyes of many VC managers, the Australian approach isn't necessarily a deal-breaker. Many US public pension funds reveal the amount of capital they committed to a fund, how much has been deployed and distributed, as well as the multiple and IRR. Superfunds must disclose the value of their interest in a fund and the size of this interest in terms of the overall investment portfolio. The amount originally invested doesn't feature.

"You could only reverse engineer the valuation of the fund if you knew the starting cost and the share of the fund. GPs we've spoken to are not worried about the level of disclosure. The concern was with company-level information," says Geoff Sanders, a partner at law firm Allens. "I only see this being a problem for co-investments and fund-of-one arrangements."

Asked if he has informed GPs about the change, one portfolio manager explains that he is leaving it until the last possible moment because there may yet be changes in the implementation of the legislation. He makes two further observations. First, the watered-down disclosure regime might still be enough to warrant exclusion from some VC funds, but probably not all. Second, this is only a problem for the minority of superfunds that have international VC exposure.

Only three Australian LPs have built meaningful global venture capital programs – QIC, Future Fund, and MLC. Of those, MLC is the only superannuation provider.

"Some industry superannuation funds have established domestic VC exposure in the last few years, but they have done it with fee concessions," says Phil Cummins, a venture partner at Greenspring Associates, which advises institutional LPs on VC exposure and invests on their behalf. "The global standard for venture – 2/20 or 2.5/30 – is just too expensive for Australian superannuation funds."

As for co-investments, AIC is still seeking clarification from regulators and government. Much depends on transaction structure and where the superfund ceases to exercise control. When a co-investment is downstream syndication of a deal that has already been negotiated and multiple LPs contribute capital to a single holding vehicle, disclosure would stop there. Even when a superfund is the only co-investor, there is usually a holding vehicle, and most of the governance rights reside with the partner GP.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.