Japan activists: Enablers or destabilizers?

The corporate governance scandal at Toshiba underlines the increasing influence of activist investors in Japan. For private equity firms, there are two sides to the coin

The private equity tilt at one of the crown jewels of corporate Japan fizzled within a fortnight. CVC Capital Partners made what is described as a broad and vague $20 billion offer for Toshiba Corporation in early April, then told the company it "would step aside" and await guidance from the board and management as to whether privatization was desirable.

Opinion is divided as to the significance of the bid. One source close to the situation suggests that it marks the beginning rather than the end: CVC has asked whether Toshiba would be best placed under private ownership, an outcome company management previously resisted. Another GP or a consortium of various interests could end up doing a deal, or there might be no deal at all, but the possibility can be discussed.

A rival school of thought is that it was an opportunistic punt, perhaps partly driven by a desire to buy time for CEO – and CVC alumnus – Nobuaki Kurumatani, who was under pressure to step down. (He did a few days later.) Companies like Toshiba are not realistic targets for PE-backed take-privates, multiple industry participants insist. The relationships within government, not to mention the national security concerns, are too deep, rendering these businesses virtually untouchable.

Alternatively, there's an argument that the bid is less significant than the circumstances that led to it. Less than four weeks earlier, Toshiba shareholders had defied the board to approve an investigation into alleged misbehavior at the company's annual general meeting last year. The probe found that management had colluded with government to rig voting, prompting the removal of four senior executives, among them two board nominees.

It represented a big win for Effissimo Capital Management, the activist investor that proposed the investigation. Alicia Ogawa, director of the project on Japanese corporate governance and stewardship at Columbia Business School's Center on Japanese Economy & Business, claims this clears the way for activists to play an even more prominent role in cleaning up listed companies.

"The way people talk about activists has changed; certain campaigns are considered a positive thing. But Toshiba is going to rest that conversation entirely," she says. "Effissimo has gone so far out of its way to ensure it dotted every ‘i' and crossed every ‘t' and used every honorific when speaking to the government. They played 100% by the rules, and Toshiba did not. That story is being heard loud and clear. It will add to the degree of sympathy people have for activists."

For PE investors, activists could accelerate an existing trend whereby corporate Japan recognizes that profitability is more important than scale. They have tracked increased deal flow from conglomerates carving out non-core assets, a result of increased emphasis on corporate governance, transparency, and return on equity (ROE). It helps when other investors, albeit with their own agendas, are pushing companies in the same direction.

"Many listed Japanese companies are trying to figure out how to work with activists. One of the solutions to answer to the activists is divestments and using the cash to make a dividend payment to shareholders," says Koji Sasaki, a managing partner at T Capital Partners. "Activists have more influence over listed companies than before. There is a need to respond to the market voice."

Getting active

Toshiba is exceptional among activist targets in terms of its size, the intricacy of the governance scandal, and the way in which it was very publicly exposed via the independent investigation. Activists were also unusually well represented on its shareholder register – for a large company – due to a widely distributed $5.3 billion share issue in 2017 intended to shore up the balance sheet.

Most activist campaigns focus on Japan's small to mid-cap space, where companies often trade below book value, and they do not involve high-profile international activist investors who typically target larger stocks that have a lot of liquidity. Moreover, the resolution, be it dividend payment, share buyback or divestment, might never be widely known.

"There is no requirement for a publicly disclosed settlement agreement. A board seat might be nominated by an activist, but no one admits that. And then a year later the entire company is sold," says one Tokyo-based lawyer. "I've worked on activist campaigns and then someone else has approached me about working on a buyout. Maybe in 30% of situations, a campaign ends up in a transaction – higher if you include share buybacks."

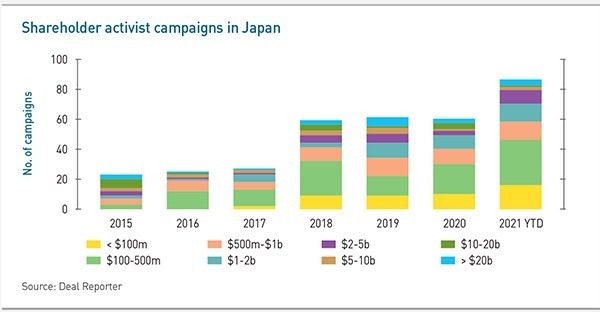

A total of 60 activist campaigns were launched in Japan last year, more than twice the 2017 total, according to Dealreporter, AVCJ's sister publication. Less than six months into 2021, there have already been 86. Only four of these targeted companies with market capitalizations above $20 billion. Two-thirds are sub-$1 billion.

It is difficult to draw a definitive positive correlation between activism and M&A, but the number of deals involving listed corporates jumped nearly 50% year-on-year in 2020. In the first quarter of 2021 alone, there were 13 management buyout proposals in the listed space, just two short of the 12-month total for last year. In 2019 and 2018, there were 10 and two, respectively.

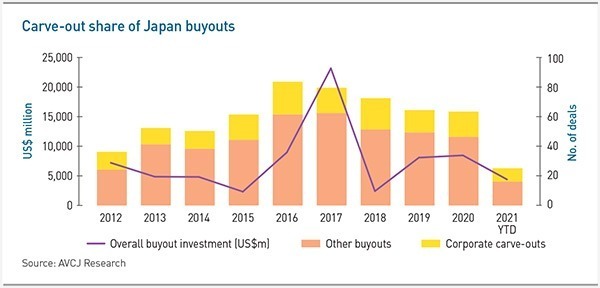

As for corporate divestments to private equity, the ascent has been more gradual: pre-2015, the annual carve-out total barely exceeded single digits; the average for the past four years is 18. They have become increasingly prevalent at the large end of the market – nine of the 12 biggest buyouts in Japan are carve-outs and eight were announced in the past five years – although most smaller GPs claim they are seeing more divestments in traditionally family succession-heavy pipelines.

Increased activism doesn't necessarily require a more aggressive approach to deal-sourcing from private equity firms. Corporate carve-outs are often years in the making. Investors establish relationships, make proposals, and maintain lines of dialogue in the hope that they can pick up assets on a proprietary basis or be well-placed to compete in an auction should opportunities arise.

CVC's acquisition of a majority stake in Shiseido's personal care business, announced in February, was the culmination of a five-year journey that started when senior executives at the private equity firm broached the possibility of a carve-out, according to Koichi Tamura, a senior partner at EY. Activist pressure will not change the mode of interaction, though it could speed up the process.

"It is easier to approach management and say, ‘Activists are worrying you, it's a headache, can we work something out?' And management is more inclined than before to think positively about it," Tamura says.

One manager in the upper middle-market buyout space adds that he will proactively approach companies that are likely targets of activist campaigns and present solutions. Some CEOs get in touch directly when they are under pressure, but most of the time transactions are intermediated.

Sasaki of T Capital has also been approached by companies looking for a white knight. He is wary of these situations because there might be little pre-existing knowledge of the industry or management team and getting involved in a public fight could lead to reputational damage. Two other sources, one an activist investor, claim that private equity firms - not T Capital specifically - take advantage of white knight scenarios to pick up assets on the cheap.

Deal blockers

The flip side is that increased activism is disrupting as well as enabling PE deal flow. While the amount of M&A involving listed corporates has risen, so has the failure rate for definitively announced transactions. In seven out of eight years to 2018, it was 0% for targets of more than $200 million in value; for 2021 to date, it is 44.4%, Dealreporter's records show. This is a result of bidders abandoning deals in the face of activist minority shareholders contesting perceived low-ball bids.

A recent example saw The Carlyle Group support a privatization of Japan Asia Group (JAG) in return for the chairman facilitating its acquisition of controlling stakes in two subsidiaries. They doubled their offer in response to opposition from City Index Eleventh – which has ties to activist investor Yoshiaki Murakami – and pulled out when the shares tendered fell short of the target. Meanwhile, City Index launched its own tender offer for JAG and continues its pursuit of the company.

Several other global private firms have faced activist challenges to privatizations in the last couple of years. Bain Capital's acquisition of printing and IT services provider Kosaido was thwarted but it succeeded in buying aged care provider Nichii Gakkan after sweetening the deal. KKR and Japan Industrial Partners (JIP) adopted a similar ploy with high-tech manufacturer Hitachi Kokusai Electric.

"Some buyout firms are getting more used to dealing with activists," says Kirk Shimizuishi, a managing director at KPMG. "It is useful to have an additional pocket ready, so you can pay up if they demand a higher share price. A lot of it comes down to putting together the right tactics – engaging with them to a certain extent, knowing how they will react to different things, and helping them get over the barrier to acceptance."

An assortment of lawyers, tender agents, and investment banks participate in this process. In proxy contests that involve the likes of Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), they help frame the proposal so that it is more likely to get endorsed. Where competing offers do not comprise only cash – it might be cash plus stock or there are proposals to address in advance of the deal proposal – there is greater ambiguity and more scope to craft an argument.

However, the lawyer who has worked on activist campaigns observes that "everyone knows MBOs in Japan are conducted at the lowest possible price that can be imagined minus 20% because there is no effective regulation of deals." As such, activist investors get involved in the expectation that private equity sponsors have the capacity to pay 20% more.

Willing to engage?

Even as PE firms become more acquainted with these situations in Japan, the activist community itself is evolving. There are still plenty of investors that are, with varying degrees of accuracy, described as greenmailers. This might be applied to "bumpitrage" players that build up positions in MBO targets and complain about the price in the hope of pushing it upwards or to any of the multitude of groups that latch onto companies in search of payoff via share buyback.

Alexander Kinmont, CEO of Milestone Asset Management, which focuses on smaller listed Japanese companies, acknowledges that activists can be effective in terms of solving the problem as they define it – improving corporate efficiency as measured by ROE – even if the broader economic contribution is less clear. He also believes some of these investors overemphasize their achievements for the sake of fundraising, claiming credit for driving outcomes that were largely predetermined.

"If you examine a lot of the denouement of activist campaigns, one is left with the feeling the whole thing was in the pursuit of headlines rather than investment returns or corporate efficiency," Kinmont says. "We've had contact with companies that have activists in their shareholder register, and they don't ever hear from the management of those funds."

The aforementioned activist investor adds that a degree of sensitivity is required to local shareholder dynamics and company management, stressing that some of the dramatic campaigns staged overseas simply wouldn't work in Japan.

ValueAct Capital is seen as the poster child for a more progressive approach. In 2019, Olympus Corporation took the unprecedented step of appointing a partner at the activist group to its board as part of a broader engagement effort. KPMG's Shimizuishi describes the ValueAct approach as going behind the scenes and working with management on portfolio optimization. The firm is selective in its targeting – the Olympus team was seen as Westernized in its thinking – and acts as a catalyst for disposals.

One of these disposals came last year when JIP acquired Olympus' imaging division. A source close to that transaction also emphasizes the willingness of Olympus to embrace reform as a trigger factor, specifically the company's ambition to reinvent itself as a medical technology business, and contrasts that with the bulk of corporate Japan. However, the source acknowledges that activists are becoming more sophisticated in their approach, making it harder for proposals to be rejected out of hand.

Misaki Capital, a firm established by a group of ex-management consultants that claims to pursue a "constructive shareholder concept," is one of several other groups highlighted in this context. Columbia's Ogawa questions how far removed its approach is from PE firm Advantage Partners' private solutions strategy, which involves making minority investments in public companies that don't want to be privatized but are receptive to value creation proposals put forward by Advantage.

Sign of the times

There is also evidence of activist investors positioning themselves where the reformist tailwinds are strongest.

Various initiatives are credited with contributing to the increased focus on corporate governance in Japan, emboldening activist investors: the corporate governance code as a means of better aligning the interests of corporate parents and public shareholders; the stewardship code as a tool for holding institutional investors to account; and the JPX-Nikkei Index 400, which assesses candidates based on criteria such as return on equity, the use of independent directors, and transparent reporting.

Industry participants attach different levels of importance to each one. The corporate governance and stewardship codes are either gradual game-changers or toothless in the absence of proper enforcement. An overhaul of the Tokyo Stock Exchange, streamlining six boards into three and tying membership to criteria such as no cross-shareholding and having a certain number of independent directors, is expected to be transformative, but there is uncertainty as to the pace of cultural change.

However, the issue that comes up time and again is compliance with environment, social and governance (ESG) protocols. Japanese companies are generally seen as lacking in this area, and activists are expected to target the weakness or use it as a platform for engagement. Several groups are said to be making proposals that address ESG as part of wider shareholder value creation.

"ESG-related divestitures should further increase. The ESG wave is definitely there in Japan and there should be cases where anti-ESG businesses are sold to private equity from the emergence of ESG activists," says Shoya Okuma, co-founder of Questhub, a proxy advisor firm based in Japan, which claims to have experience of activism-related deals.

He points to Oasis Management's recent approach to packaging container manufacturer Toyo Seikan Group Holdings as an example of a traditional activist embracing an environmental and social agenda. Alongside proposals for performance-linked remuneration, changes to corporate structure, greater empowerment of management and a share buyback, Oasis called for enhanced climate-related financial disclosure to improve transparency on sustainability issues.

Japan has a fundamental appeal as a relative value play. As a second activist investor puts it, everyone has too much cash, a nice office building, a listed affiliate, and room to cut costs. While campaigns tend to come in waves, it is argued that the current one could be protracted, albeit with some fluctuations. The power of policy reforms and the combined weight of scandals like Toshiba, which underscore the notion that management isn't always right, cannot be underestimated.

Private equity players stand to benefit from this trend but given the amount of dry powder these GPs are sitting on, so can the sellers. "Larger fund sizes lead to more competitive bidding and higher returns for sellers in an environment where greater emphasis is being placed on corporate governance. This raises logical questions from activists and other shareholders: Why aren't you embarking on a more aggressive divestment program?" says Paul Ford, a Japan-based partner at KPMG.

The virtuous cycle of more divestments begetting more private equity deal flow will at some point get broken by valuations becoming too rich. For now, though, investors have enough conviction in the turnaround and growth story with these assets that they are continuing to pay up.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.