China regulation: Taming the giants

Recent regulatory reforms suggest that China will not let the growth of large technology companies go unchecked. The implications could be far-reaching, not least for VC investors and start-ups

Ant Group presented the Beijing-based chip design company with a potentially transformative proposal. It would lead a Series A round and use the company's technology in an instant-claim car insurance product that relied on image-recognition technology – a fast-track route to monetization for a young start-up.

Then came the caveat, the founder recalls. He was told that taking funding from Ant Group meant refusing any approaches from Tencent Holdings, Baidu or Meituan.

This is not an unusual dilemma for a Chinese start-up. Many have been forced to take sides over the years, accepting that alignment with Alibaba puts Tencent off-limits and vice versa. It is not just about funding. Doing business with one – and benefiting from its vast ecosystem – may mean never doing business with the other.

"Meituan, JD.com and Pinduoduo are all backed by Tencent. WeChat's traffic has helped them to become giant platforms in the battle against Alibaba's e-commerce empire," says Chuan Thor, founder of AlphaX Partners, a China-focused VC firm. "In the same way, Alibaba invested in [and then took control of] Ele.me to create a new force that would challenge Meituan's ubiquitous delivery business."

Meituan, JD and Pinduoduo are not the only beneficiaries of Tencent's capital and resources. The Hong Kong-listed technology giant has accumulated an enormous portfolio of interests. As of January 2020, it had invested in over 800 companies, including 160 unicorns. Tencent's holdings in listed companies alone, excluding subsidiaries, were worth $138 billion as of September, a tenfold increase on 2016.

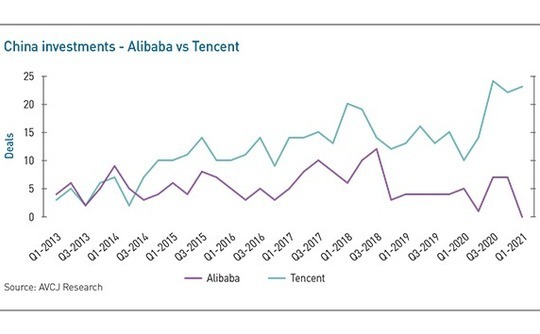

AVCJ Research has records of 379 investments by Tencent in China between 2013 and 2020. Over the same period, Alibaba completed 177. More recently, however, their paths have diverged. Tencent was involved in 22 deals in the final quarter of last year and there have been 23 in 2021 to date. Alibaba has only three to its name since November and none this year.

Winds of change

The timing of this near cessation in activity coincides with Ant Group's IPO being pulled amid a flurry of speculation that regulators were looking to cut it – and Alibaba founder Jack Ma – down to size. New guidelines were introduced that will likely dramatically curb the scope of Ant's business. Meanwhile, local antitrust regulators targeted Alibaba over alleged monopolistic business practices.

Gauging the government's true motivations is near impossible, but the implications of its recent actions stretch beyond Alibaba.

The antitrust probe targets all e-commerce platforms that insist merchants use them as an exclusive distributor. Separately, several local internet giants have been cautioned about anti-competitive pricing in the group buying space. Moreover, ByteDance is emboldened enough to pursue legal action against Tencent for blocking links to its short video platforms on WeChat and QQ.

Taken together, these developments suggest a desire to clip the wings of big tech. PE and VC investors are reluctant to overplay the still-nascent situation, but it could have significant consequences for China's start-up ecosystem, which has to some extent been defined in recent years by Alibaba and Tencent's outsized influence.

"Ant's suspended IPO best illustrates the regulators' changing attitude towards platform internet companies. It represents a shift from tolerance to equal regulation. No matter what kind of platform you are, the regulator supervises you by identifying your main business. In Ant's case, the main business is lending, so it should be regulated in the same way as traditional banks," one industry participant observes.

"The official release came out less than three months after the draft version. Such speed reflects the regulator's determination to strengthen the supervision of the platform economy," says Frank Jiang, a partner at local law firm Zhong Lun.

Divisive structures

Major reforms include a change in the treatment of variable interest entity (VIE) structures, commonly used by overseas investors to gain exposure to industries in which foreign participation is restricted.

An antitrust filing must be made in China when the parties involved in a transaction both have annual domestic turnover exceeding RMB400 million ($61 million). Companies with VIEs haven't filed, even if they meet the qualification threshold, because they exist in a legal gray area. The Ministry of Commerce refused to accept their filings for fear that doing so would constitute official recognition of VIEs.

"It has become conventional practice that a VIE structure doesn't submit anti-trust filings, even though the regulator never officially agreed to such an approach," says Fay Zhou, a partner at law firm Linklaters.

Several hundred antitrust filings are made each year, but the number would double if companies with VIE structures were included, people familiar with the situation tell AVCJ. VIEs are inextricably linked to VC investors, but from an antitrust perspective, strategic investors are the bigger concern. Large tech players could theoretically establish commanding positions in segments with minimal oversight.

"China's anti-monopoly law serves as a good regulatory tool for overseeing healthy development and orderly competition in the economy, including digital platforms," says Zhong Lun's Jiang. "In the past, notifiable transactions involving VIE structures have often been kept off the merger radar. Today, Chinese regulators appear to be open-minded towards this structure and VIE-companies can even list directly in the mainland."

Zhong Lun worked on the first VIE-related filing approved by the State Administration for Market Regulation's (SAMR) Anti-Monopoly Bureau last July. It was an artificial intelligence (AI) joint venture established by MiningLamp Technology, a big data player backed by Tencent, and fast-food chain Yum China.

Nevertheless, the regulator was still refusing to accept VIE-related filings as late as November, according to industry sources. This resulted in several global private equity firms pulling out of deals because they were uncomfortable with the situation.

One month later, in mid-December, fines of RMB500,000 were imposed on participants in three deals for gun-jumping – otherwise known as implementing transactions prior to receiving regulatory clearance. They involved an Alibaba investment entity, Tencent-backed China Literature, and Hive Box, a self-service package drop-off and pick-up operator that counts SF Express as its largest investor.

"The fines were relatively small. Thus some of our clients proceeded with deals even though SAMR wouldn't accept the filings," explains a lawyer with an international firm who asked not to be named. " If there was no anti-monopolistic impact of the transaction, in the past, a client would often rather risk being fined and close the deal quickly."

Upping the ante

Since then, the filing process has speeded up. Zhong Lun's Jiang claims that, in 80% of cases, there is now only a one-month wait in between submitting a filing and receiving approval. Meanwhile, penalties will escalate. Amendments to the Anti-Monopoly Law (AML) are expected within the year that could see fines set as high as 10% of a transgressor's previous annual revenue.

This represents a substantial risk for companies. Several lawyers tell AVCJ that they have clients reviewing historical deals. One lawyer adds that all the major internet companies are currently under investigation, which means digging through transactions from recent years. Explanations must be given for undeclared deals.

Xu Liu, an antitrust-focused researcher at Tongji University, has highlighted several suspected gun-jumping cases involving Ant Group on his personal blog. Among them are Ant Group and Alibaba's acquisition of Ele.me and the purchase of Tian Hong Asset Management, which went on to develop Yu'ebao, a money market fund that enables Alipay users to generate a return on their unutilized cash balances.

"The regulator has the authority to revisit and take action against other historical deals that should have made antitrust filings and failed to do so. But, based on the relevant authority's past practice, it is reasonable to expect that they might not proactively do so," says Ning Zhang, a partner at law firm Morgan Lewis. "They have already sent a clear message to the market by imposing punishment on these four major cases."

However, what constitutes a historical deal is open to debate. If the illegal behavior led to the creation of a new enterprise that continues to exist, any penalty would not be considered retrospective, argues Susan Ning, a partner at law firm King & Wood Mallesons. Rather, the penalty would relate to current behavior.

There is no misunderstanding as to how the regulator defines control. An investor holding a minority stake in a company could still be deemed as having control if it possesses certain kinds of veto over operations.

In this context, MBK Partners was fined RMB350,000 by SAMR for failing to provide notification of its purchase of a 23.53% stake in spa chain Shanghai Siyanli in late 2019. It amounted to a warning to investors not to apply the loosest standards when assessing whether a minority transaction involving a VIE company counts as a control deal.

"They think if it does not involve the two most critical veto rights – on the business plan and on the budget – it does not constitute control. In fact, in other industries, the general practice is that a veto on the appointment of executives or on investments in large assets can also be considered as control," says Linklaters' Zhou.

Some strategic investors are expected to give up veto rights on critical issues to avoid antitrust filings.

It is worth noting that even when the standard thresholds for an antitrust filing are not met, regulators can still initiate investigations if the target company is in a sensitive industry such as defense or satellite communications. The same applies to industries where market substantial share is concentrated in a relatively small group of participants.

"It was bad that Ctrip was able to acquired Qunar, a VIE company, [in 2015]. The market became too concentrated and customers had fewer choices," says a partner at a local VC firm. "It is important declarations are made in advance because there could be changes in market structure after the fact that are difficult to correct."

Information angle

Such market concentration has already led to price-discrimination, with the technology sector a prominent offender. More than half of respondents in a 2019 survey by Beijing Consumers Association claimed to have experienced discrimination. Online travel agencies, e-commerce platforms, and ride-hailing apps were the most widely cited problem areas.

Meituan, Ele.me and Ctrip have all been subject to consumer complaints, typically because non-members of their services are charged more than members. However, improper practices vary in nature. For instance, a Fudan University professor conducted experiments in five cities and found that a ride-hailing app allocated more expensive vehicles to users with pricier phones.

Liyong Zhou, a general manager in the VC unit of Shanghai STVC Group, one of China's earliest state-backed LPs, notes that investors can be hurt by price discrimination as well as consumers. "When companies generate profits inappropriately it can lead to valuation bubbles, which brings risk to investors," he says. "We have serious discussions with our GPs about not backing these companies."

The antimonopoly guidelines for platform economy businesses include various measures to address data-driven misbehavior. These range from stripping offenders of intellectual property, technology or data to creating open platform infrastructure to modifying platform rules or algorithms.

"At least the customer should have certain rights, for example, to delete data or to transfer it to other platforms or to ask the platform to explain data usage," says Ning of King & Wood Mallesons. "We are seeing more regulations giving rights to consumers and imposing more controls on how platform companies use data."

Industry sources suggest that data resources, especially personal financial data, ultimately might be defined as public property, so they cannot be claimed or owned by any one company. A national data center could be established to store and manage this information. This would potentially impact the business models of companies that rely on big data and algorithms.

Until now, technology companies and investors have paid little attention to these risks. Their current priority is commercializing existing data resources. However, government relations are a lingering concern. Companies are encouraged to maintain lines of dialogue with local authorities to stay on top of any imminent regulatory changes.

"We've backed a fintech platform and its business scale is much larger than that of its competitors. However, there are certain markets the company cannot enter because it doesn't have strong government relationships and is unable to obtain a license," says one investor. "In tier-one cities, this is less of a concern. It's a problem in less-developed areas where governments are over-protective of local businesses."

Balance of power

Initial feedback from the PE and VC community on the threat of regulatory action against big tech in China tends to focus on specific industries. There is a sense that investors believe sweeping conclusions are premature.

Moreover, they do not anticipate any immediate change in the Alibaba-Tencent hegemony. For the time being, regulators are more focused on the internal operations of these companies, rather than their external investments. And most start-ups are still happy to do business with big tech.

"Some companies would prefer not to take money from either side because they don't want to disclose their key data and operations figures to investors that are backing their competitors. But in most cases, it's seen as an endorsement," says Chibo Tang, a partner at Gobi Partners.

As for investment agreements that prevent companies taking money from certain groups, it often comes down to the balance of power. In certain cases, the dynamics are actually reversed, and companies only bring investors into in-demand funding round if they promise not to back an assortment of competitors.

"If a company doesn't want an investor to sell its stake to a competitor, especially if the stake carries a board seat with it, that restriction has been around for a long time," says Maurice Hoo, a partner at Morgan Lewis. "But in recent years, some companies have tried to prevent investors from making separate, independent, passive, non-controlling investments into other companies, some of which are direct competitors, while others may only have tangential connection with their business."

With this in mind, it is worth noting that China's tech sector is in a continual state of flux. Though the BAT – Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent – still occupy positions of strength, their dominance is not preordained. The TMD – Toutiao, Meituan, Didi – were positioned as emerging rivals several years ago. At the time, Pinduoduo and Kuaishou were nowhere, but now they are major players.

Some investors are confident that new platforms will continue to emerge, perhaps barely understood by the likes of Alibaba and Tencent or at least not reliant on these companies' B2C might. Regulation will remain a feature of the market, but it is unlikely to stop these upstarts from creating their own powerbases and ecosystems.

"China is such a large and complex market, it's not easy to maintain a monopoly," says Wayne Shiong, a partner at China Growth Capital. "There are always chances for newcomers."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.