GPs & SPACs: Filthy lucre?

The global SPAC craze is percolating into Asia, with private equity firms among the sponsors. LPs aren’t necessarily comfortable with the development, but there’s only so much they can do about it

The communique to LPs hits all the right notes. It emphasizes how "this strategic initiative" will deliver an "immense structural advantage in the global technology landscape," it dangles the promise of "an additional avenue to add significant value to portfolio companies," and it speaks to wider ambitions of creating a "multi-stage investment platform." The writers conclude by restating the offer of a follow-up call to address any further queries.

A small but growing number of Asia-based GPs are composing similar messages as they seek to contextualize decisions to launch special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs). The meetings that follow will likely reflect the patchwork of agendas that make up the LP community. Initial responses shared with AVCJ range from weary indifference to measured wariness to unfettered indignation. Some managers, meanwhile, claim to have received positive feedback.

SPACs might have been designed to create controversy. They are lauded as an innovative route to a public listing – turning the IPO process on its head by raising money before a target asset is identified. They are tagged as peak-of-cycle entities that will collapse when the market turns, leaving retail investors out of pocket. And they are incredibly lucrative for the supporting sponsors, which means they can be equally divisive.

Moreover, GP-LP exchanges might be colored by a nagging sense that this time it's different. The latest SPAC wave in the US is larger than any before it and features some high-caliber participants, among sponsors and investors. Rather than fall from grace amid a supply-side glut created by the current frenzy, SPACs could have a permanent place in the investment landscape.

"A lot of fat is going into SPACs, but sophisticated investors should view it as a neutral tool. It comes down to whether you can attract high-quality institutional capital and high-quality assets. If you can do both, there's nothing to fear," says Denis Tse, who leads the cross-border investment strategy at Korea's ACE Equity Partners. Last month, a SPAC launched by ACE completed a merger with a US semiconductor company.

Feeding frenzy

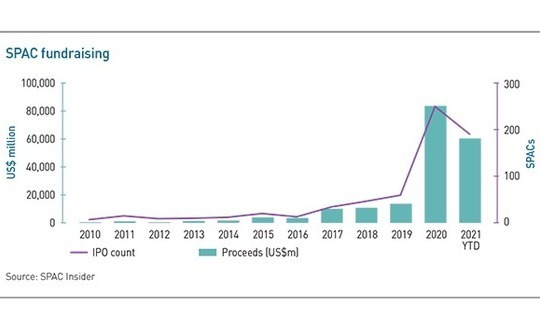

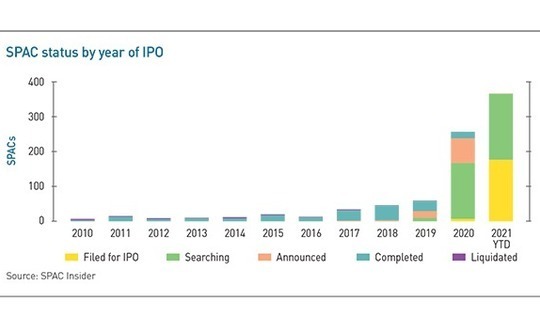

The rise of SPACs in the US has been meteoric. A total of $83 billion was raised last year across 248 offerings, according to SPACInsider, a website that tracks SPAC activity. This compares to $43.6 billion from 172 offerings over the preceding five years. In the first two months of 2021 alone, 189 SPACs raised $59.9 billion.

Private equity investors aren't the only ones getting involved; operating executives and hybrid groups – comprising bankers, dealmakers, and operators – are equally prolific. Asia-based sponsors tend to be PE players and hybrids, although the likes of corporates and family offices are getting more interested.

"There's no shortage of people who want to raise a SPAC, but we are being selective," Laskowski adds. "Ideally, you want a proven PE or VC fund with substantial AUM [assets under management], a good track record with respect to who they have backed, and substantial returns. You also want to see they've done deals in the space they're targeting."

Within the private equity bucket, SPAC sponsors can be subdivided into three categories: solo dealmakers who raise money on the back of a personal track record; global managers with ample resources where SPACs sit alongside numerous strategies and structures; and mid-cap firms where the sponsor entity is usually owned by the managing partner and its positioning vis-à-vis the firm can vary. The third group draws questions from LPs about potential conflicts of interest and use of resources.

For private equity firms, SPACs are an opportunity to pursue deals that don't fall within the remit of their funds. Primavera Capital Group, for example, has raised a SPAC focused on global consumer companies that are looking to China for growth. The firm's PE funds primarily invest in China-based assets, and even in situations where Primavera does look overseas, the targets require some development work. Anything that goes into a SPAC must be IPO-ready.

Among VC firms, the deal-sourcing gap is even wider. "SPACs are interesting because they allow us to take a bite in later-stage investment without forgoing the economics of early-stage deals," says Jeffrey Chi, a managing partner at Vickers Venture Partners, which has raised a SPAC. "We often pass on deals because they are too far along. Now we can take advantage of that."

Once an LP is comfortable that a SPAC isn't taking deals away from the main fund, there remains the question of how much time key personnel will spend on the new structure. Why, it might be asked, are members of the firm engaged in an opportunistic self-enrichment exercise instead of devoting themselves fully to the PE funds they are paid to manage?

"These people are in the top half of the 1% and some are in the top 10% of the 1%. They are set for life. They should be 100% focused on generating the best possible returns for the funds and putting any spare nickels and dimes into the funds," says one LP. "How these SPACs are justified is absolutely beyond me. Anyone who is doing it should stop immediately."

This represents one of the more extreme responses. LPs are not enthused by the prospect of SPACs – unless it is a third party taking out a company owned by a portfolio GP – and they stress the importance of conflict management and transparency. But some are more bothered than others.

One investor relations executive observes that complaints come more readily from foundations and fund-of-funds than from pension funds and sovereign wealth funds. Similarly, US-based LPs might be more comfortable with SPACs than their Asian peers because they have seen plentiful use of these structures in the domestic market. There is also a desire to see how the phenomenon plays out.

"The fact I'm answering with hesitation means there is a lot to be learned about how these things are being used," says a second LP. "A lot of these practices are being adopted in the US markets and some of it is translating through to the Asian market. We have to learn what these practices mean and where and how the boundaries are being pushed."

History lessons

There is some SPAC history to work from in Asia. Simon Luk, a partner at law firm Winston & Strawn, helped two Hong Kong-based sponsors launch SPACs in the US more than two decades ago. The trend reemerged in the mid-2000s before ending abruptly with the onset of the global financial crisis. Many of those SPACs ended up underperforming, which left the structures carrying a stigma.

US-based investors began to reengage with SPACs in a meaningful way in 2017 and this began to trickle through to Asia. New Frontier Group, an investment platform established by two former executives at The Blackstone Group and a Hong Kong entrepreneur, Sing Wang, ex-head of North Asia at TPG Growth, and New Silk Route (NSR) founder Parag Saxena all raised SPACs in 2018. Progress hasn't been smooth.

Saxena failed to agree a merger prior to the end of its 18-month allotted period – after which investors in the IPO get their money back and the sponsor loses its principal capital – and won an extension by sweetening the deal. A merger with Reviva Pharmaceuticals was completed last December and the stock closed at $8.91 on March 1. Saxena has since launched a second SPAC with a 24-month acquisition window and a more focused remit in terms of sector and geography.

In each case, the stock crept upwards ahead of a merger announcement and dropped significantly on completion as investors opted to exit. Those who subscribed to SPACs launched by Wang and Saxena received units comprising one share and one redeemable warrant. Once the deals were done, they could stay invested or redeem their shares for cash.

Hedge funds are frequent subscribers: investments are subject to a fixed timeframe; there is the potential for equity upside if they like the deal; and at a minimum, they can redeem on completion and recover their principal plus interest and some upside on the warrants. (More recently, given the frothy market, SPACs have offered only one-half or one-third of a warrant in each unit and they pay no interest.)

The trick is attracting and retaining long-only mutual funds as investors once the hedge funds cash out. Few manage it. Academic research cited in Bain & Company's 2021 global PE report found that redemptions left SPACs with only 25-50% of the capital initially raised. Of those that completed mergers between January 2019 and June 2020, the average loss in value in the six months post-merger was 12% versus a 30% gain for the NASDAQ Composite Index. After 12 months, the average decline was 35%.

Weak secondary market performance doesn't mean the sponsor loses money. They must put in risk capital, typically 2% of the IPO size for underwriting fees and $2 million for other expenses. But they are rewarded with free shares equivalent to a 20-25% equity stake in the listed entity plus one warrant – which converts at the standard price of $11.50 per share – for every dollar of risk capital committed.

If a SPAC IPO raises $200 million and the stock jumps from $10 to $20 post-merger, a sponsor that invested $6 million in warrants would be sitting on a liquid position worth $157.6 million – a 26.3x return. Even if the stock doesn't move from $10 million, the implied return is 9.3x.

Alignment preserved?

To appease LPs concerned that these economics would result in private equity managers-cum-SPAC sponsors taking their eye off the ball, some GPs bring the entire operation in-house. Vickers and Olympus Capital Asia have both structured sponsor entities as fund portfolio companies.

"Once we decided sponsoring a SPAC is an attractive opportunity that allows us to leverage our investment experience and track record, we wanted to structure it in a way that is complementary to our PE strategy. The last thing we want is to create potential conflicts of interest with LPs in our funds," says David Shen, a managing director at Olympus. "We also wanted target companies to know that they can capitalize on all of our experience, resources, and network."

Other SPACs make similar claims, but the dividing lines can be blurred. The managing partners or CEOs of three China-focused private equity firms – Primavera, Ascendent Capital Partners, and Hopu Investments – all own or part-own sponsor entities, yet their strategic positionings differ markedly.

While the Primavera SPAC is described as an affiliate of the PE firm, its access to the firm's track record and network is emphasized, and the relevance of the track record to the investment remit is explored in detail, the Ascendent structure does nothing of the sort. A source close to the GP stressed that the managing partner would spend limited time on the project. One individual from each firm sits alongside the managing partner on the SPAC management team. Other team members are independent.

In the case of Hopu, the managing partner chairs an advisory board rather than serve on the management team. The prospectus references a contractual arrangement between Hopu, the SPAC, and the sponsor regarding office space and administrative services, and states that there will be "arrangements" with Hopu regarding deal-sourcing and execution support.

Venture capital firm B Capital Group has taken a different route to resolving the conflict of interest issue by hiring a dedicated partner to handle its SPAC, according to LP sources. This may mollify investors who point to the separation of teams and fee streams that come with the introduction of a new strategy when asked how they want to see GPs handle SPACs. A key difference is that a SPAC is only supposed to complete one deal in 18 months.

Regardless of the structural nuances, there is some frustration as to how managers have shared their plans. A third LP claims one of his GPs was "not upfront" on the matter, burying it at the end of a briefing and then brushing it off. The IR executive, whose firm has launched a SPAC, adds: "Some GPs have got the positioning wrong. They went to the LPAC [LP advisory committee], said we want to do this, the LPAC asked them why and they didn't have a strong answer. We spent time shaping the story."

Share the love

There are other ways to placate LPs, such as offering them a piece of the deal. A SPAC fundraise is sometimes complemented by a forward purchase agreement (FPA), which works much like a fund commitment and is drawn down by the sponsor at time of merger. Alternatively, LPs could be included in the PIPE deal that accompanies the merger – or de-SPAC process – and helps offset redemptions. This opportunity is usually extended to a small circle of investors because of the need to move quickly.

ACE's Tse, who describes SPACs as "PIPEs on steroids," advocates bringing LPs into the PIPE because it solidifies the alignment of interest above and beyond having the sponsor as a portfolio company. He notes that any fund investment in a SPAC would be relatively small; it is the $6 million in warrants that match the sponsor's principal capital commitment.

"If you think of the multiplication effect of that $6 million combined with a PIPE return that goes alongside the de-SPAC process, it looks like a sizeable transaction, from a fund perspective and from an LP co-investment perspective," Tse says. "It is also a compelling proposition for anyone selling to the SPAC. Say you are raising a $150 million PIPE and one third is already spoken for by the GP and by co-investors. That's a strong alignment of interest and it conveys confidence in the PIPE."

Once again, responses vary by LP type. Some sovereign wealth funds, for example, are actively looking to invest in the PIPE portions of SPACs under their public market strategies. Other investors are more dismissive. The first LP questions whether a late-stage asset at a late-cycle valuation is as attractive as the marketing suggests. Asked what would make him happy with a portfolio GP doing a SPAC, the answer is quick and simple: all the profit must be rolled over into the GP commitment to the next fund.

This raises the broader question of how much influence LPs really have over managers. Several sources claim to know of GPs on the fundraising trail that are holding back on SPACs but plan on launching them as soon as possible. Moreover, it is widely noted that limited partnership agreements (LPAs) give managers considerable leeway to do what they want, and LPs are often loath to stop them.

Another observation is that a SPAC might constitute a personal investment and PE and VC players – as compulsive dealmakers with extensive sourcing networks – have plenty of these. SPACs happen to be more publicly visible. This is not presented as a justification for a mid-market GP raising a SPAC, more a recognition that it is difficult to limit the scope of activity unless it is clearly in conflict with the main fund.

The caveat is that managers will be held to account based on fund performance. It is easy for LPs to cite conflict of interest concerns when explaining a decision not to re-up or negotiating better terms during a difficult fundraise. "As long as you can maintain the perception that you are doing well and everything is under control, LPs will let you get away with anything," says one GP.

IPO 2.0

Few industry participants expect SPAC fundraising to continue at its current pace. With so many structures looking for deals, competition for IPO-ready assets is intense and valuations are being driven up. SPACs will likely fail to find targets or merge with sub-optimal businesses, resulting in weak secondary market performance as companies don't deliver on aggressive earnings projections.

When a SPAC works, though, investors and advisors claim that it works well. It is faster and more efficient than a traditional IPO, and routinely described as closer in nature to an M&A process. A SPAC will move quickly to secure exclusivity, given its 18-24-month timeline.

"In certain situations, a de-SPAC is a better mousetrap," says Citi's Laskowski. "With a SPAC, unlike a traditional IPO, you have the ability to directly share financial forecasts with investors. You can better control the narrative and highlight your growth plans. Additionally, with a de-SPAC process, I can tell you within roughly two months with a fair degree of certainty the deal size and proceeds. With a traditional IPO it takes 6-9 months, and the valuation is effectively fixed on the last day of the roadshow."

The PIPE investors serve as the gatekeepers, essentially validating the investment thesis through their participation. SPAC advocates point to the quality of the institutional investors, at least in offerings backed by blue-chip sponsors, as evidence that the structure has more staying power this time around.

Shen of Olympus notes that capital is already converging on the higher-quality sponsor universe, a trend he expects to continue, in turn creating better track records and greater specialization in terms of strategy. "While there will certainly be further evolution of economic terms and structures, we believe SPACs will remain a viable alternative to funding as companies think about how they want to access the public market," he says.

This is by no means a universal view. Plenty of private equity practitioners are adamant that history is repeating itself and SPACs – "a classic bull market instrument" – will fade away once macroeconomic conditions change, and other asset classes offer a more attractive risk-reward. But if they do not, LPs will have to devise a longer-term response. Chi of Vickers suggests that clearer language will be inserted into LPAs as to what GPs can and cannot do, but this is conditional on having enough bargaining power.

"There are firms that try to get away with it by telling the LPAC it's just one deal, not a big strain on resources, and beneficial to the platform," the IR professional adds. "But smarter LPs realize if GPs can do it once, they will do it again and again. It could become a fully-fledged business model. And when you are getting paid that much upfront, will you pay attention to anything else?"

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.