Asia travel & hospitality: Ready to board?

The outlook for international tourism remains uncertain, but this hasn’t stopped some private equity and venture capital investors targeting travel and hospitality assets in Asia. It pays to be selective

It's not unusual for Ocean Link, a Chinese private equity firm that exists at the nexus of consumer, travel and technology, to receive inbound inquiries from foreign companies. In the past, they have tended to be tourism and hospitality players looking for someone to help them penetrate the China market, but COVID-19 has pushed that down the priority list. Now it is all about survival.

"China expansion is less of a focus point – they want money. For travel businesses globally, debt funding has become extremely difficult to obtain. You might be able to refinance through existing lenders, but that's all," says Tony Jiang, co-founder and a partner at Ocean Link. "We've been approached about capital raising at very low prices. Logistically it's impossible to do due diligence, but that aside, it's difficult because we might end up catching a falling knife. We need more clarity on the recovery of the global market."

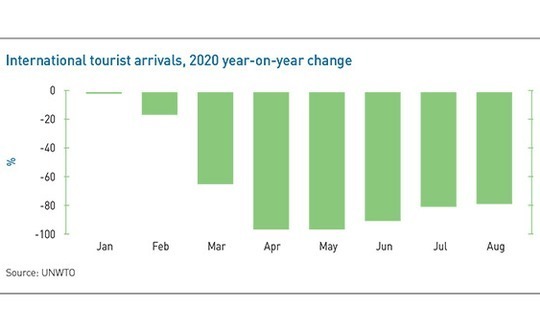

With most borders still closed, the outlook is bleak. International tourist arrivals fell 70% year-on-year in the first eight months of 2020. This translates into a loss of $730 billion in export revenue – more than 8x the post-global financial crisis period, according to the UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). The consensus view of the UNWTO's expert panel is that a rebound won't come before July 2021, with a return to pre-pandemic levels unlikely until 2023.

The International Air Transport Association's (IATA) prognosis is equally grim. It projects revenue passenger kilometers (RPK) will be down 66% year-on-year in 2020, with a return to 2019 levels unlikely before 2024.

For many PE and VC firms, travel and hospitality is off-limits, simply because they feel unable to underwrite deals in a climate of uncertainty. A few, however, are still willing to take the leap, spurred by a combination of revivals in domestic tourism, specific local considerations, and a belief that the right asset, aligned with the right management team, will prevail. In most cases, they are getting in at heavy discounts and they aren't put off by talk about structural shifts in demand.

"Once things open up, there will be a surge in outbound travel," says Kuo-Yi Lim, co-founder and a managing partner at Monk's Hill Ventures, which has exposure to travel start-ups and is looking for more. "The dynamics are different for business and leisure travel. Leisure travel is primal, it's about human relationships and enjoying life. You can't satisfy that through Zoom. Even with business travel, maybe 80% can be done by Zoom, but 20% still needs to be in person."

Big-ticket buys

Investment in the Asian travel and hospitality sector is $1.9 billion year-to-date versus an average of $2.4 billion for the preceding eight years, according to AVCJ Research. This category captures a range of food and beverage assets that primarily serve domestic consumers. Leisure and entertainment – physical assets that can be visited rather than content – and airline-related businesses have received a $3.7 billion and $1.4 billion, respectively. The eight-year averages are $1.5 billion and $918 million.

Of the $7 billion put to work across these three categories, three deals that can be linked definitively to travel and tourism account for more than half. Each has its own distinguishing characteristics.

First, Bain Capital's A$3.5 billion ($2.5 billion) acquisition of Virgin Australia Holdings. The beleaguered airline had collapsed into administration carrying nearly A$7 billion in debt after COVID-19 wiped out demand. Bain had to find a restructuring solution that was commercially viable yet met the needs of an array of stakeholders. The goal is to create a leaner airline with a strong balance sheet.

Second, Hahn & Company bought Korean Air's in-flight category and duty-free businesses for KRW990.6 billion ($835 million), with the airline retaining a 20% stake and committing to a long-term service contract. CEO Scott Hahn explained his investment thesis to AVCJ in August: Korea cannot live without international air travel given that exports are 50% of GDP; and the rapidly-expanding Incheon Airport is set to become one the busiest hubs in the world.

"It is Australia's largest theme park operator, with an 80% market share, and five of those are on the Gold Coast. It also accounts for one third of the Australian cinema market. Those businesses were completely closed due to COVID-19, revenues went to zero, but we were able to measure through the COVID-19 experience what the cash flow burn would get down to and how much capital we would need to put into those businesses over the next 12-18 months as part of the transaction," Ben Gray, founder of BGH, told the AVCJ Forum last month.

BGH had to sweeten the deal several times to get it over the line, a development that coincided with the Gold Coast theme parks reopening. Bookings are expected to be strong over the coming months, even though international visitor arrivals have dried up. Domestic activity already accounted for three-quarters of the country's A$60.8 billion tourism industry in 2019. Meanwhile, the A$38 billion Australian tourists planned to spend offshore has nowhere to go, according to Commonwealth Bank of Australia. Domestic tourism and home improvement are expected to be the big beneficiaries.

Cinemas are more of a challenge. They have reopened but there isn't much product available, with US studios reluctant to sanction new releases. There is also some consternation over Warner Bros deciding to make films available simultaneously in cinemas and on HBO's streaming service in 2021, though this is limited to the US. Foxtel renewed its multi-year contract as Warner's Australia distributor in May.

BGH underwrote the Village Roadshow deal in the expectation that the theme parks wouldn't reopen until January, according to a source close to the situation. It also plans to put enough liquidity on the balance sheet to support the company under a scenario in which COVID-19 lasts another 24 months. There is co-investment in the deal, but one LP who looked at it says that his investment committee had reservations about exposure to cinemas and theme parks.

"What we've found in our co-investment business over time is the deals that do well are the ones that meet EBITDA projections in the first and second years. If you get them wrong, it's hard to recover," the LP explains. "With any tourism-related business, we would worry that they are being too optimistic in underwriting EBITDA in 2021 or even 2022."

A key point here is what the manager uses as the baseline for EBITDA calculations – last 12 months, 2019 full year, forward looking, or something else? It's a theme that comes up time and again in conversation with dealmakers: sellers are treating the COVID-19 period as an exception, baking in assumptions of a swift return to pre-pandemic business levels. In some cases, there might be evidence of this happening; in others, it is impossible to tell.

Domestic bliss

Nevertheless, the notion of pivoting to meet the needs of domestic travelers can be compelling. It extends beyond Australia into large-scale markets like China as well as more affluent economies such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Several start-ups have raised new funding rounds on the back of rapidly executed business model transformations.

MyRealTrip, a Korean super app that offers guided tours, transportation bookings and hotel reservations, relied on cross-border business for 99% of its revenue. Within a month of March – the nadir for companies across the region – it was rolling out domestic trip offerings. Jeju, an island off the country's south coast, became the prime target because it is one of the most popular destinations for those coming from Seoul and they usually spend at least two nights.

Meanwhile, the start-up is keeping international travel appetites sated with virtual tours voiced by experienced guides. This isn't a big money-spinner, but it keeps international tour guides – a key asset – engaged with the business until travel restrictions are removed.

"A lot of people are complaining about COVID-19, saying they need assistance from the government, but these guys recognized they were fighting for their survival and that they could ultimately benefit from building up market share in domestic travel," Kim says. "They had some M&A offers, decent offers, but the CEO didn't want to take them. We loved it."

Lim of Monk's Hill takes a similar line in explaining his decision to re-up in $75 million Series C for Taipei-based online tour package vendor KKday a couple of months ago. There was conviction that the team could keep its cost structure in line with the on-the-ground reality and emerge as a leader in the space.

KKday, which counts Taiwan, Korea, Hong Kong and Southeast Asia as its core markets, went domestic by partnering with hotels on staycation packages comprising rooms, meals and spa treatments. In certain markets, outdoor activities are on the agenda. The company also sought to deepen ties with local experience vendors by introducing a software product that helps them manage inventory, pricing, and interaction with online customers.

Fundraising began pre-pandemic and KKday didn't collect the $100 million originally targeted, but it was able to rely on support from a combination of existing and strategic investors. "Our investors take a medium to long-term view on the opportunity at hand," says Victor Tseng, CFO of KKday. "Tours and attractions are a $50 billion market and online penetration is only 15%, compared to 60% for hotels and flights."

Both Altos and Monk's Hill are also invested in start-ups that are unable to do domestic pivots. In these cases, the onus is on bringing down cash burn and waiting out the storm. Mafengwo, the Chinese equivalent of TripAdvisor, falls into this category. More than 70% of its revenue comes from cross-border travel, and despite attempts to target domestic tourism, consumers require less guidance in their home markets, notes Jiang of Ocean Link, an investor in the company.

However, the sudden shift from aggressive expansion to internal economies – Mafengwo was doubling in size every year, now it isn't hiring or spending any money on user acquisition – offers the luxury of time. Jiang estimates the company could continue operating for up to seven years at its current burn rate without needing to raise additional capital.

Debt burdens

Ocean Link's portfolio divides into three categories: e-commerce, grocery delivery and online education businesses that have seen increased demand because of COVID-19; those that took an initial hit but have rebounded well, such as domestic resorts and car rental operators; and the likes of Mafengwo and airport lounge business Dragonpass that have international exposure. There are 20 companies in total and 16 aren't carrying any debt.

"We don't have any companies that have run out of cash and shareholders need to put more in. While one company has leveraged financing, the banks were lenient and agreed to waive the covenant test quickly. Then the business bounced back," Jiang says. "It is fortunate that most deals in China don't rely heavily on leverage."

Even where there is leverage, lenders have been accommodating. Trans Maldivian Airways, a seaplane operator whose fleet was grounded when the Maldives closed to tourists in March and hasn't seen much of a revival since it reopened, is the one high-profile exception among PE-owned businesses. The company agreed a standstill with creditors after missing an interest payment in May, but this expired at the end of August with no restructuring plan in place, Debtwire reported.

The same month, some banks started selling their debt positions to distressed credit investors looking to take ownership of the business. Bain, leader of a consortium that acquired Trans Maldivian in 2017 backed by a $305 million term loan, has essentially been squeezed out. A source close to the situation refers to it as a "debt-for-debt" transaction with the new owners leveraging up the airline again and waiting for tourism demand to rebound. (It is worth noting that Trans Maldivian was done by Bain's Asia private equity team; Virgin is a special situations deal.)

For the most part, if government support programs aren't enough for a challenged company to delay its day of reckoning, then banks will grant covenant holidays and interest payment waivers. Peter Graf, head of leveraged finance in Credit Suisse's Asia Pacific financing group, highlights the behavior of Australian lenders, but the same applies to other banks in the region. "They don't like taking the keys from companies; they prefer solutions that do not involve running the business," he says. "If you want to refinance a deal, existing lenders are the first port of call. They have the most to lose."

Private equity firms have generally been very proactive in getting forbearance, putting liquidity in place, and agreeing extensions on covenants to see them through year-end. Meanwhile, financing for new deals – especially in areas like travel and hospitality – is likely to feature lower leverage levels and tighter covenants with more bespoke tests attached. Lenders typically don't share in the equity upside, so they are paying closer attention to downside scenarios.

BGH agreed four transactions between June and October. Two of them – Village Roadshow and TripADeal, an online travel agent that is in hibernation until COVID-19 passes – are long recovery plays. The other two, a health centers business acquired from Healius and dentistry chain Abano, took an initial hit but have since rebounded. The financing for Healius included additional debt capacity that can be drawn subject to the business clearing certain performance hurdles. For Village Roadshow, existing lenders rolled over and BGH put in second lien debt in addition to equity.

There is an emphasis on getting a seat at the table to make sure companies are trending in the right direction, ensuring a degree of comfort with the post-COVID-19 world. To some extent, this helps address concerns about EBITDA multiples.

"The leverage multiple for something like Village Roadshow might be relatively low, based on pre-COVID-19 EBITDA, but based on EBITDA today, it's massive," says Graf. "People are looking at it from a first-principles perspective, so pre-COVID-19 to some degree doesn't matter anymore. It's a question of how the business is operating today, what is the run rate and EBITDA for the last month assuming no seasonality, and what is the outlook for the next 12 months."

Where possible, lenders might look beyond whether there is enough cash flow to make interest payments and pay down a substantial portion of the principal during the holding period, choosing instead to focus on underlying value. The question then becomes: if the company doesn't recover in 12 months and there's a sale, what would lenders get out of it?

"For businesses that have taken a hit, where there is a need for liquidity financing, it is more likely to be structured against collateral value rather than against earnings multiples. With companies in real estate, such as shopping mall operators, the focus tends to be on the unencumbered asset base and getting an LTV [loan-to-value] structure," says Giles Abbott, a managing director at Zerobridge Partners, an Asia-focused debt advisory firm.

The great game

To some extent, the market is playing a giant game of wait-and-see. It operates on several levels. There is a lingering debt problem and how long lenders are prepared to delay taking substantive action if tourism doesn't return to pre-COVID-19 levels within 12-18 months. No one is expecting the market to fall off a cliff, but the lack of a clear line of sight on travel bubbles and vaccines or serious working capital depletion could force the issue.

Then there is the broader question of structural change and the possibility that pre-pandemic demand can never be revisited. This can be company-specific. For example, some of the other bidders for Virgin are said to have asked for sweeteners such as guarantees on market share on key routes and government support for fuel purchases. Bain was happy to proceed without these, but will it impair the business recovery? The private equity firm declined to be interviewed for this story.

The question also cuts across geographies and industries. Will international travel rebound aggressively, with reduced demand from business as companies embrace videoconferencing as a cost-effective alternative the only drag? That scenario means different things to different people – it would be far worse for Virgin than for KKday – but attempts to form consensus views are undermined by the ongoing uncertainty.

As they probe business models and map out scenarios, investors know they are standing before a door – in terms of deal access and valuations – that will not remain open indefinitely. In some cases, it might have already closed. "We learned from looking at deals in the global financial crisis that we wanted to focus on situations where something had to happen, due to the debt or liquidity issues. In all four transactions we've signed up, there were issues that had to result in an outcome in some form," Gray told the AVCJ Forum.

Another takeaway from the global financial crisis is a reluctance to make new investments when existing portfolio companies require remedial attention. BGH entered the pandemic with only two deals to its name. Moreover, the firm's senior advisors include Jane Halton, previously secretary of Australia's Department of Health and chair of the World Health Organization's sub-committee on communicable diseases. Her early insights into COVID-19 encouraged the GP to take swift action.

This dynamic applies to private equity and venture capital investors alike. "We are seeing start-ups with interesting ideas and concepts for travel that we are getting conviction around. When the first surge happens, they will be well placed to come out of the gate strong," says Lim of Monk's Hill. "No other industry has so much pent-up demand. It's like riding on a surfboard, looking for that wave."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.