China data centers: Real estate plus

Valuations are rising in China’s data center industry as speculative real estate-style investors flood the market. Experienced players are willing to spend more time building scale

In case anyone was in doubt about the popularity of data centers as a China investment theme, two deals closed on the same day in June featuring two of the largest private equity firms in Asia.

First, Hillhouse Capital paid $400 million for a 3.9% interest in US-listed Chinese data center developer GDS Holdings as part of a private placement that saw existing investor ST Telemedia Global Data Centers put in $105 million. Around the same time, it was announced that the Blackstone Group would invest $150 million in 21Vianet, a data center platform backed by Singapore's Temasek Holdings.

Not all local investors are impressed. "They are optimistic about this industry but they cannot find suitable targets in the primary market, so they invest in through PIPE, a channel for them to get on board," says one investor. "But we want to earn the price difference between the primary and the secondary market."

One month later, CPE – formerly CITIC Private Equity – secured its own deal with GDS. They have jointly acquired a greenfield data center project that will represent a RMB2.6 billion ($371 million) investment upon completion, scheduled for 2023. CPE can then sell its interest to GDS.

Joint ventures are a standard way of exploring new markets and developing knowledge and capabilities, but the criticism of many investors targeting data centers is they skip over the knowledge part. Data centers are treated like property deals, underpinned by speculation on land price appreciation. GDS and 21Vianet are helpful proxies. The former has seen its market capitalization triple in the past 12 months; the latter's valuation has doubled.

"Prices are ridiculously high, so investors are paying an enormous premium to get in," an infrastructure-focused investor tells AVCJ. "We won't touch it, because I can't calculate how to break-even at these prices."

Demand drivers

There structural reasons for the appeal of data centers. COVID-19 and remote working – which, in turn, drives demand for data – is one. The Chinese government's new infrastructure initiative is another. Data centers, feature alongside semiconductors, artificial intelligence, charging stations for electric cars in the list of new infrastructure areas intended to define the next generation of economic growth.

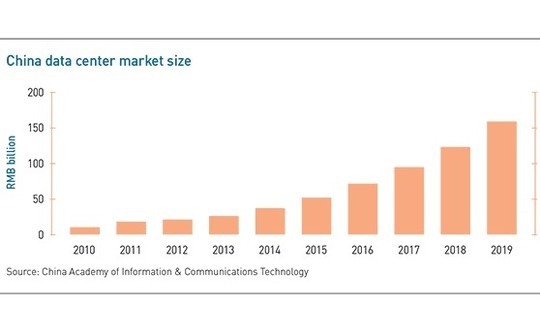

In short, data centers represent a long-term play regardless of the current valuation bubble. According to the China Academy of Information & Communications Technology (CAICT), the market has grown from RMB10 billion in 2010 to RMB158.6 billion in 2019.

"Data centers have been one of the best performing asset classes in mature markets. It's a unique hybrid product of real estate and TMT [technology, media and telecom] infrastructure. It has the best of both worlds: a high growth profile from the data explosion and defensible cash flows. That's why capital flows in from real estate, infrastructure and general private equity funds," says Ellen Ng, head of China real estate at Warburg Pincus.

Contrary to what many people think, data center operators don't supply computers or servers. They provide power and cooling infrastructure; their customers install networking hardware as required. "Think about it like this: If a data center costs $5 million to build, $1 million is contributed by data center providers and the customers have to invest $4 million" explains Drew Chen, a managing director from Bain Capital's TMT vertical.

This business model has two benefits for data center operators. First, asset depreciation is a 10 years-plus cycle because they don't need to supply computer servers. Second, as long as occupancy is high enough to meet the break-even threshold, cash flows are sticky and stable. A typical contract with a customer lasts for more than five years.

"Customers tend to be very cautious when they pick a partner. Once the customer comes in, they rarely move out because of the high transition cost," says Warburg Pincus' Ng.

While telecom companies are China's largest data center operators, accounting for 65% of the market, independent players are growing quickly. Private equity investors are keen to support these scaling up efforts, with internet companies the primary target customers.

For example, Bain paid RMB990 million last year for a majority stake in China's ChinData, which has since been combined with Southeast Asia and India-focused Bridge Data Centers to create a pan-regional platform. "We are probably the largest hyperscale data centers in Asia," says Chen. "Our customers are primarily cloud providers. We do a lot of built-to-suit (BTS). That's increasingly more common."

Similarly, 21Vianet is the go-to partner for Alibaba Group. The company also serves Microsoft, JD Cloud, Tencent Cloud, and Huawei Technologies. GDS claims that the co-developed project with CPE has "received strong interest from an existing hyperscale customer to take all of the capacity."

Strategic imperatives

While these independent providers are actively courting internet giants as customers, the giants are keen to build their own data centers. Kuaishou, a social media-oriented live streaming platform, recently announced it would spend RMB10 billion on a greenfield data center in Inner Mongolia. Tencent Holdings plans to build large-scale facilities with millions of servers nationwide.

However, this doesn't necessarily mean they will end up competing with the independents. Amazon Web Services rents 60% of its data center capacity, with the remaining 40% having been developed in-house over the past five years. Using external partners can deliver greater capital efficiency and faster market access.

"The main challenges of operating data centers in Asia are the complex and various local regulations. For internet companies in this region, more than 80% of their data center capacity comes from third-party operators," says Rangu Salgame, chairman and CEO of Princeton Digital Group (PDG), a pan-Asian data center operator backed by Warburg Pincus.

Nevertheless, some local players look beyond the obvious internet customers. For CDH, the emphasis is on margins. Ye observes that these giants often put their own data centers in lower-tier cities because planning restrictions make it difficult to build in tier-one locations.

"We never touch tier- two or tier-three cities. All my investments are either in tier-one cities or on the outskirts of these cities," says Ye, whose team has visited more than 100 projects and invested about RMB1 billion in the space. A single large-scale deal CDH has in the pipeline is expected to double the amount deployed.

In this aspect, data centers are much like other real estate asset sub-classes: location is key.

The bulk of China's data demand comes from Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, where the largest corporates are based. They don't want to be too far away from data centers for ease of maintenance and fast data transfer speeds. For a live-streaming game player or a hedge-fund manager, even a 0.1-second delay makes a difference.

Large internet companies are building data centers in more remote areas for a different reason – to deal with so-called cold data, such as backup information or the huge computing demands of artificial intelligence (AI) training.

The ability to get power and land in first-tier cities gives data center operators a tremendous competitive edge, but once again, local and regional players have different objectives. Ye divides data center customers into two groups – retail and wholesale. Retail players are generally financial institutions, governments and large corporates, while wholesale targets tend to be internet giants.

"Wholesale can guarantee basic cash flow, but retail can capture higher gross profit. The more a data center is in the core area of a city, the more we are inclined to retail customers. I would be happy to have 50% wholesale and the rest for retail," Ye explains.

Bain prefers to build larger data centers even though that means looking for sites beyond the traditional outskirts of cities. Building restrictions are responsible for driving them further out. "We tend to focus on a little bit outside a tier-one city and build much larger scale data centers, which are much more cost-effective," says Chen. "Usually it's a bit cooler than within the city, you spend less on power and energy supply."

According to the CAICT, the power usage effectiveness (PUE) of data centers in China – a measure of energy efficiency based on total facility power versus IT equipment power – is 2.2, much higher than the US average of 1.9. For large-scale facilities, the PUE drops to 1.63; for super-large facilities, it is 1.54.

While Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen are curbing new construction, exceptions are made for low PUE. Beijing will allow new and expanded data centers for cloud computing with a PUE below 1.4. Shanghai requires new facilities to have a sub-1.3 PUE. For rebuilds, it is 1.4.

Reliability issues

Besides location, the most important data center characteristic is reliability, which means design and operation are closely scrutinized. For example, a new entrant to the market built a facility and approached Alibaba as a potential customer. Alibaba concluded that the ceilings weren't high enough for its hyper-scale hardware and the power density was insufficient. It walked away.

These kinds of anecdotes are recited by multiple investors when they stress the importance of choosing operators with strong track records.

In 2016, the Ponemon Institute, an independent research house specializing in information assets and IT infrastructure, analyzed the downtime costs of 67 data centers worldwide. It found that the downtime cost was $7,900 per minute, a 41% increase on 2010. The average "going down" accident cost was $690,000 with a maximum of $1.7 million. Failures can have a devastating impact on corporate reputations.

"No matter what the size of the data center, what country it is located in, and the technology that goes in, the way we design and operate facilities is as good as the best in the US or in China," says PDG's Salgame.

The need for consistent service quality inevitably draws regional investors to pan-Asian platforms. Last year, PDG confirmed three project acquisitions region-wide as part of a $500 million expansion initiative. It bought a majority position in XL Axiata's data center portfolio in Indonesia, a suite of development-stage projects in China, and a 100% stake in a Singaporean data center to be used by IO Data Centers, a major US-based operator.

The company is willing to consider greenfield projects, acquisitions and carve-outs from telecom companies in the pursuit of scale. CDH, for its part, concentrates almost exclusively on greenfield, largely due to concerns about squeezed margins elsewhere. "We give up many projects when they turn to be too expensive," says Ye.

While inexperienced newcomers are pushing prices up and returns down in China, a less saturated market niche involves data centers overseas that service Chinese customers.

"When we're bidding on projects outside China, we are typically one out of two, at most three interested parties. The level of competition is a lot more rational. Probably the runway is even longer because the penetration today is quite low," says Bain's Chen. He adds that the likes of Alibaba don't really need help with capacity inside China; it's outside where independent providers can really add value.

The private equity firm's data center strategy is described as a platform approach – backing providers that can achieve scale through replication rather than investing in one-off assets. The objective is to become the provider of choice for a clutch of leading cloud players and growing in tandem with them. At the same time, it can facilitate exits for others by absorbing one-off assets into its platform.

Warburg Pincus takes this one step further. The GP wants to take the model that worked for ESR, another portfolio company, in warehousing and apply it to data centers. This means creating a fund management entity and shifting data centers from providers' balance sheets into third-party funds. LPs would invest in these vehicles, with mature assets generating stable but attractive yields.

"There is a large supply-demand gap between the urge to deploy capital in this sector and the supply of quality operators in the region," Ng explains.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.