L Catterton Asia: Unhappy families?

The merger of Catterton and L Capital was unique in its size and scope, creating the world’s largest consumer-focused private equity firm. However, perspectives on the experience remain polarized

Four-and-a-half years on from the merger of Catterton and L Capital, the firm now known as L Catterton would rather talk about the future than the past.

"I hear these questions and I scratch my head. This is a lot about history," says Michael Chu, the firm's co-CEO. "The narrative that's more relevant is do we have a high-performing capability on the ground in Asia that is fully integrated into our overall platform, and are we excited about the franchise we have today? And the answer is yes. The characterization of this as a problematic merger is simply false. It's been a great success and if we had to do it all over again, we would."

L Catterton's assets under management (AUM) have tripled in size since 2016, while its footprint has spread from North and Latin America into Asia and Europe. But the merger with L Capital is a story that has played out over several years. Viewed through an Asia lens, it tracks Fund III, which closed at the end of last year. The raising, deployment and ultimate performance of this vehicle will be a key consideration for many LPs in assessing the combined entity in the region.

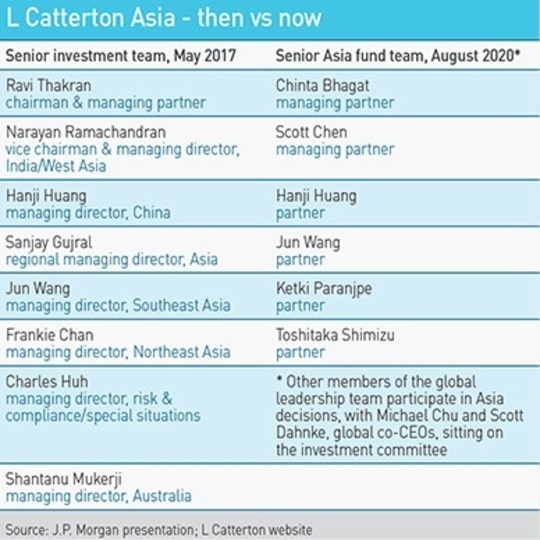

An added twist is turnover in senior personnel in the Asian and European operations that were originally L Capital. In Asia alone, six of the eight individuals that made up the senior investment team when Fund III launched have departed. L Catterton argues that it has recruited, retained and released in a way that strengthens the overall franchise. It is for others to decide if the L Capital DNA has been augmented or replaced, whether that matters, and – by extension – whether the merger should be viewed as success or failure, or something in between.

"I've never seen a real merger work in private equity," says Mounir Guen, CEO of placement agent MVision, without referring to L Catterton specifically. "It's extremely difficult to assimilate the DNA of two different firms. Each one has its own fingerprint, the way it sources, the way it interacts, the way it monitors companies."

Logical combination

When the merger was consummated in 2016 it was positioned as a coming together of complementary parts. The blueprint emerged when Catterton shared with LPs its desire to create a global presence, with Asia the next port of call after North America and Latin America. LVMH, L Capital's parent and a Catterton LP, suggested that combining the two businesses could immediately deliver a global platform.

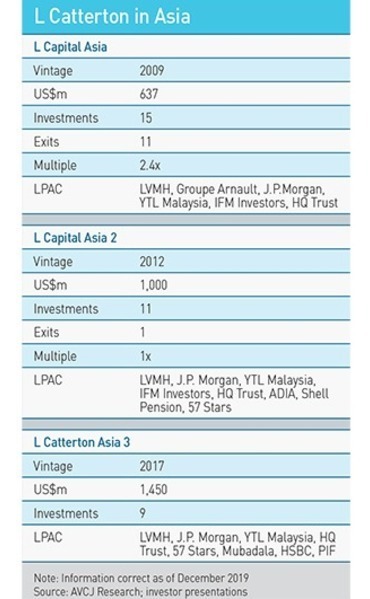

At the time, Catterton had $5.5 billion in AUM dedicated to the Americas. L Capital Europe was established in 2001 and had raised EUR1 billion ($1.1 billion) across three funds. Its Asia counterpart emerged in 2009 and closed two funds with $1.6 billion in commitments.

The partners of L Catterton took a 60% interest in the combined entity, with LVMH and Groupe Arnault, the family holding company of LVMH founder Bernard Arnault, owning 20% each. It would have over $12 billion in AUM across six strategies once various successor funds closed, including the third Asia vehicle. The remit of that fund – backing aspirational mid-market brands – would remain the same, but with a wider scope in terms of categories and deal sizes.

Speaking at the AVCJ Forum in November 2016, 11 months after the announcement of the merger, Chu and Thakran were effusive about the progress made. "Ravi and I kid each other it's like we've known each other for decades. That's the depth of the collaboration," Chu said. "And I would say the success of the merger … is really predicated on some very simple foundations. The industrial logic of putting our businesses together was both obvious and compelling."

Thakran added: "We generally have one way of reaching out, one way of working, one way of building value – and that brings synergies. When you talk about GP mergers not being successful, perhaps it's because those GPs don't come from a similar culture or a similar focus or similar way of doing things. There were similarities in all those for us and it has made it so much easier."

They emphasized the effort that had gone into integration: Thakran had made 10 visits to the US and Chu had traveled to Asia five times; partner off-sites were held involving representatives from different geographies; a third-party consultant made recommendations on integration best practice; and the economics were structured so that partners shared in the profits generated across the platform and received carried interest from every fund.

"Whenever there is the thought of a transaction it always makes strategic and financial sense on paper," says Wen Tan, CEO of Azimuth Asset Consulting, a provider of specialist advice to asset managers and asset owners. "But it's one thing saying that; it's totally different in terms of execution. It is easy to make a whole set of errors during integration – errors around people, processes, systems, products, how the transaction is sold to investors."

Conflicting expectations?

The remarks Chu made in 2016 about Asia as a key piece of an increasingly global consumer puzzle characterized by technology, attractive demographics, and a rising middle class, stand the test of time. His views on business models defying geographic borders are unchanged, and being able to tap these opportunities through a global platform is why he views the merger as a success. Team turnover, the significance of which he downplays, doesn't get in the way.

"We walked into this merger with zero expectations. Given what we knew about the platform and the work they had done, we wanted to take our time in getting to know people and to be deliberate in how we should think about the integration," says Chu. "We had no expectation with regards to the people, who was going to stay, who was going to leave. But what we knew was that through this combination we would instantly create a global platform, the likes of which nobody in this industry has built, and that was our primary objective."

This notion of success is not shared by all industry participants, including former L Catterton employees in Asia. It is worth noting, however, that many refer not to what Catterton has achieved through the merger but how it got there and the potential implications.

First, while Catterton may have gone into the deal with no expectations, members of the L Capital Asia team certainly had expectations – in terms of economics and autonomy – and they believe these were not met.

What was promised in terms of equity ownership in the merged entity appears to be in dispute. Speaking to AVCJ in March 2016, Thakran referenced "a shift from a partner-led platform to a single sponsor-led platform," with members of the Asia team set to own a portion of the 60% management interest. An investor presentation dated May 2016 mentions that "allocation of Global AMC share" has been agreed for Thakran but not for the rest of the senior leadership team.

It is claimed that neither Thakran nor any of the others received an equity interest on completion of the merger. A former L Catterton Asia team member says: "We were told we were partners and partners get equity. We never got it." Asked if specific promises were made, the individual observes that as partners in the GP there is a natural expectation of equity ownership.

Thakran declined to comment on this matter. However, participating in an AVCJ event last month, he detailed plans to launch his own PE firm and expressed an interest in partnering with non-Asian GPs that want exposure to the region. Asked what he wanted from a partnership, Thakran mentioned "real equity in the business, not first-class citizens and second-class citizens."

L Catterton states that all partners are stakeholders in the firm or eligible to become stakeholders, which includes sharing in the global profit pool and having carried interest from every fund (though skewed towards the funds they work on). Moreover, the profit pools exist at the global level and stakeholders participate regardless of their fund's contributions, whether or not they generate profits. L Capital, as a wholly-owned subsidiary of LVMH, did not operate in this way.

Freedom to choose

As for autonomy, L Catterton claims the Asia team, post-merger, has as much if not more than it did under LVMH. Across the firm, most investment and portfolio management decisions are led by local teams, with Chu and co-CEO Scott Dahnke sitting on investment committees. At the same time, there's a desire to integrate best practices across the platform, which suggests some standardization and central control.

This is another area in which expectations were not met. The May 2016 presentation specified that Thakran retained complete autonomy over day-to-day management, with the exception of annual budgeting and top-level personnel decisions. However, one of the first things L Catterton sought to do was remove the Asia CFO Gilbert Ong, two former team members say. This was resisted. There were also efforts to run investor relations out of New York.

"In hindsight, there was a clear attempt by the Asia leadership team to stay independent. Catterton entertained this for some time, but after two years, they realized they had to be closer or the merger wouldn't make sense," a fourth former Asia team member reflects.

Multiple industry participants observe that centralized coordination of these functions is normal practice for a global private equity firm and express surprise that it would ever be otherwise. "You can't be a global operation without controlling your franchise. You need to put in a COO for financial controls, and then IR is global – the Asia IR team at KKR reports to New York," an Asia-based GP says.

Following the launch of Fund III in 2017, one LP recalls an L Catterton pitch meeting attended by members of the Asia team and a group that traveled from the US. The LP felt that at times they appeared to be pushing separate, almost contradictory, messages rather than a unified narrative. Nevertheless, a couple of closes with around $1 billion in commitments – against an overall target of $1.25 billion – came in 2018. The third close in June 2019 was on $1.3 billion.

By this point, a trickle of senior-level departures had begun. Sanjay Gujral, the regional managing director for Asia who had some COO duties, departed mid-way through 2018. By the end of the year, two more managing directors had gone, namely Frankie Chan and Charles Huh.

Gujral and Chan were two of six senior investment professionals subject to a collective key person clause in the Fund III limited partnership agreement (LPA), according to a marketing presentation dated May 2017. If three or more of them left the firm, it could trigger a key person event, potentially allowing LPs to terminate the investment period. Thakran was identified as a singular key person so his departure alone would trigger a key person event.

A more substantive development came in early 2019 when Thakran revealed plans to spin-out and raise a growth fund, with L Catterton's blessing. About a dozen senior members of the Asia team were involved, from the investment and operations sides of the business. They included, in addition to Thakran, Narayan Ramachandran, Shantanu Mukerji, and Jun Wang. All three were among the six identified in the key person clause. The group also agreed to do a management buyout of Funds I and II.

L Catterton declined to comment on the matter, but several sources say Chu visited Singapore in May 2019 and took part in a townhall meeting at which he endorsed the spin-out and presented it as a joint decision. However, when the proposal was put before the Fund III LPAC in June, it was rejected.

Senior team members were invited to attend a subsequent LPAC meeting in November. While they were told that everything would revert to normal, those linked to the spin-out were not included in discussions with LPs. "They wanted to put the genie back in the bottle, but that was impossible. They knew it, the LPs knew it," says a fifth former team member.

Changing the guard

In August, Chinta Bhagat, formerly of McKinsey & Company and then co-head of private equity at Khazanah Nasional, joined as a managing partner and co-head of Asia, working alongside Thakran.

Guen of MVision offers a post-merger scenario that, while not identical, captures the dynamics at play: "Say you are head of the firm in the region, you aren't totally comfortable with the merger, and then you're told that someone else will be coming in to run the business. You've gone from everyone reporting to you to everyone reporting to someone else, and the first thing she does is get rid of 60% of your people. She wants to make sure people are loyal to her, not to you."

It was around this time that a split emerged within the team, according to several former members. Those who were part of spin-out or aligned themselves with Thakran claim they were essentially frozen out; their job titles remained but duties were reassigned, leading to exclusion from meetings, emails, and engagement with portfolio companies. "We were relocated from the 18th to the 13th floor [in the Singapore office], literally separating us," says one.

Some express concerns about the health of Fund II and whether certain issues are being properly addressed. L Catterton insists that it is deploying whatever resources are required. As of year-end 2018, 10 of the 11 investments were still active and the portfolio was valued at 1.3x, according to documents seen by AVCJ. Twelve months on, there had been no further realizations and the gross multiple was down to 1x. Given the heavy exposure to fashion and retail, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been significant. Australian swimwear brand Seafolly went into administration in June.

Meanwhile, the departures continued. From Gujral to Thakran himself – who became chairman emeritus in June and claims to be focused on realizing exits from Fund I – there have been about a dozen. Most of them were focused on operational or functional areas, rather than investments. Of particular note are Ramachandran and Mukerji, given their status as key persons on Fund III.

Mukerji declined to comment on the circumstances of his exit. However, it is claimed by two other sources that Mukerji's day-to-day involvement ceased several months before he parted ways with L Catterton at the end of December. Furthermore, while his departure was discussed, they say nothing was put in writing until the collective key person clause was modified (and the singular key person clause removed). The precise timing of these changes is unclear, but Fund III closed with $1.45 billion in commitments at the end of 2019.

"The key person trigger in the LPA did what it was supposed to do – it allowed us to confer with our LPAC on our thinking and collaboratively arrive at the right outcome," says Dahnke. "The LPs have voted with their pocketbooks: they like where we are and the team that has been assembled."

These changes received unanimous support from the LPAC, whose members represent about 80% of the total capital in Fund III. And the fund is 50% larger than its predecessor, suggesting comfort with the product. L Catterton observes that its investment team remains largely in place.

A quirk of the Asia franchise is the concentration of the LP base and a heavy reliance on private banks, which typically receive upfront and ongoing service fees from the PE firms they work with as well as fees from the high net worth customers they put into funds. J.P. Morgan clients alone are said to account for about 50% of each of the first two funds and 40% of the third. Other Fund III LPAC members include Mubadala, YTL Malaysia, 57 Stars, HQ Trust, HSBC, Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund, and LVMH.

LPAs tend to have three levels of decision-making power: LPAC only, a majority of the overall investor base by capital committed, and a two-thirds majority of the investor base. (For extreme actions like GP removal, it might be 75%). For Fund III, winning LPAC support is sufficient to pass each of these tests, which might leave smaller LPs feeling disenfranchised.

"If we had known more of what was going on, it's possible we would have killed the whole thing. When we asked questions, they said they couldn't discuss it because the matters hadn't been discussed at the LPAC. It wasn't very transparent," says one LP, who isn't on the LPAC and came in after the first close. "We took comfort from the fact that, despite the risks of putting these two firms together, Catterton was a better franchise, so the whole would be more than the sum of the parts."

Time will tell

To those who backed Fund III early and saw the senior team that was marketed to them morph into the senior team that exists today, perhaps those changes – and the global platform angle – were compelling. L Catterton started with 20 professionals in Asia, including six at partner-level. There are now 25, of which seven are partners, led by Bhagat and Scott Chen, a recent hire from TPG Capital in China.

Another perspective is that Fund III was already 45% drawn by the end of 2019 with seven investments completed – the next deal didn't come until April 2020 – and investors willing to accept the status quo. They simply had no appetite for further disruption. The LP observes that everyone in Fund III would likely have to re-underwrite the GP completely before considering a re-up for Fund IV.

Dahnke's take on the situation is this: "All things considered, was it perfect? No. Could it have been done better? Probably, but I'm not sure we have specifics around that, and regardless I don't think the outcome would be any different." If anything, he wishes they had moved faster on integration.

The conflicting views on the merger will likely never be fully reconciled. If anything, these polarized responses underline the difficulties of uniting different teams and cultures. In any industry, M&A brings change: it may create or destroy value; it benefits some more than others. In private equity, where value is inextricably linked to people, internal and external relationships, and customized thought and execution processes that bind it all together, finding the right chemistry isn't easy.

"There are many examples of successful add-on acquisitions," says Azimuth's Tan. "However, it's a lot more challenging in merger situations and maybe L Catterton in Asia is a case in point. In mergers, it is often harder to reach a common consensus as to the best way forward."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.