GPs & climate change risk: Material matters

Climate change risk is becoming a broader debate within private equity, taking in the long-term impact of floods, droughts, and fires on portfolios. Most GPs have yet to turn thought into action

The Greater Bay Area (GBA) initiative is intended to create an economic powerhouse in the Pearl River Delta, anchored by Hong Kong, Macau, Shenzhen, Guangzhou and seven other cities in Guangdong province. Over the next decade, its GDP is expected to hit $4.6 trillion, a near threefold increase on 2018, and its population will swell by 17 million, equivalent to two New York cities.

But could climate change stymie this growth? Eight of the 11 GBA cities are as dry as the Middle East, based on per capita water resource assessments by China Water Risk, a non-profit consultancy. Meanwhile, the region also represents a flood risk. Extreme rainfall events were happening once in 21 years in 2000, up from once in 41 years a century earlier, according to Hong Kong Observatory.

This is not solely a dilemma for the GBA. Economies across Asia have insufficient water resources to support their development and global warming will only exacerbate this situation, leading to droughts and floods of greater frequency and extremity. The clustering of assets along vulnerable rivers is another factor. More than 280 cities are served by 10 rivers that flow from the Hindu Kush Himalayas; five of these river basins already face high or extreme water stress.

For the likes of China and India, where the liquidity crunch is particularly severe, business-as-usual isn't an option. Governments must act, which suggests a policy risk layered on top of the existing climate risk. Private equity investors – most of whom are currently preoccupied with carbon – are urged to consider their water risk exposure, almost irrespective of sector and strategy.

"Emissions are not what's going to get you. What is the likelihood of somebody hitting you with a climate carbon tax? [President] Macron tried that in France, didn't do the groundwork, and ended up with a revolt. The likelihood of running out of water is much higher," says Debra Tan, head of China Water Risk. "Every year we delay action, water risk rises – and pretty much all climate impact relates to water. More advanced investors have cottoned on to this."

It signals a fundamental extension in environment, social and governance (ESG) coverage, from assessing the impact of business on climate to assessing the impact of climate change on business. A factory might have a string of certifications for carbon neutrality and water efficiency, but if it stands in a water basin that will be empty in 10 years, it may still end up a "stranded asset" that no one wants to buy. Navigating these issues requires a mindset that is forward-looking and broad in scope.

"When you talked to GPs about climate change it was almost always greenhouse gas emissions," says Steve Okun, CEO of APAC Advisors, a consultancy that specializes in ESG, sustainability and stakeholder engagement. "Now there is a recognition that climate change is impacting businesses in multiple dimensions. It goes into water scarcity, flooding, droughts, landslides. And then there is more climate regulation. As a PE firm, you ask if you're compliant and if the companies you're investing in are compliant, but it is so broad now and everything is happening so fast."

Asset vs portfolio

While an increasing number of private equity firms might appreciate that more questions need to be asked, relatively few are taking material steps to answer them. Emissions remains the starting point: Measuring the carbon footprint of a portfolio, establishing which companies are the key contributors, and evaluating ways to reduce the negative impact.

"If a manager has done this and is already seeing big reductions in the companies they are working with, that makes me very happy. If they have also done forward-looking scenario analysis and can identify the companies at risk over the next 5-10 years because of water or flooding, that would make me incredibly happy," says Adam Black, head of ESG and sustainability at Coller Capital. "A majority of managers are thinking through how they are going to do that but haven't started doing it yet."

A minority of the minority that have begun scenario analysis are able to discuss science-based targets and the prospect of making their portfolios net zero carbon by a certain date.

There is no perfect correlation between ESG sophistication and GP size, but the greater resources of global firms confer an advantage and their exposure to global best practices suggests a degree of standardization. While EQT and The Carlyle Group differ in how they approach climate change at a high level, there are some similarities in execution. Metrics are tracked on a portfolio basis and climate risk is assessed on a case-by-case basis, concentrating on areas relevant to specific investments.

The latter came into focus last year when Carlyle was looking at coastal real estate assets. Recognizing that climate change could have a material impact during the 3-5 year holding period, a specialist consultancy participated in due diligence. "They helped us model out the potential for sea level rise and extreme weather-related events, what that could do from a damage and an occupancy perspective. They also helped us model out insurability. Policies typically run for one year, so have to think about pricing increase," says Megan Starr, Carlyle's global head of impact.

This is different from taking a 10-year view on climate risk across the entire portfolio. Indeed, Carlyle hosted its very first climate scenario analysis workshop – where those considerations were on the agenda – as recently as last month.

Turnkey places longer-term scenario analysis in a separate category, referred to as supply chain resilience. Most of the demand for this service comes from listed companies that have established ESG processes and regard supply chain mapping and science-based targeting as the logical next step. "Not many in the private equity world are coming to us, although I expect they will," Wines says. "We are in discussions with a few asset managers."

Smaller, local private equity firms are unlikely to be among the first movers because their portfolio companies are usually at a preliminary ESG level. Richard Folsom, co-founder of Japan-based Advantage Partners, observes that the devastating earthquake and tsunami of 2011 prompted a reexamination of business location and supply chain diversification. For now, though, his firm is focusing on basic corporate citizenship and community impact.

Kushal Chadha, a Hong Kong-based partner at PwC, echoes this sentiment. He is seldom asked to set up ongoing performance measurement systems based on climate metrics, while scenario testing only comes up in conversations with London-based ESG executives. Certainly, among Chinese GPs, the prevailing ESG demand is to have something simple installed ahead of a fundraise.

"Climate change comes up more and more and the context is often ‘I have a meeting with my LPs, they gave me a to-do list six months ago and I haven't done much about it, what should I be doing?' The more proactive ones will be looking to launch a new fund but recognize they haven't invested much on the ESG side. They want help positioning themselves in a better light," he explains.

Get regulated

If the global GP landscape can be segmented into a handful of advanced practitioners and a mainstream of managers that are thinking about action or disinterested, much the same might be said of LPs. Cornelia Gomez, head of ESG and sustainability at Europe-focused PAI Partners, notes that climate comes up in relatively few LP questionnaires and the questions are "still very shy." For example, they rarely ask directly about carbon footprints or scenario analysis.

The exception is Europe – Gomez singles out the Nordics, the Netherlands and France – which should come as little surprise given its status as the cradle of climate regulation. In recent years, compliance requirements for listed companies across the region, at national and EU level, have been strengthened and carbon reporting is beginning to filter into the private space as well.

The 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change, the SDGs, and the 2018 Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change all called for decisive action and the EU responded. Of the eight major economies that together account for two-thirds of global carbon emissions, it is the only one gearing up to extend its Paris Agreement commitment of limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius by 2100. In the nearer term, the trading bloc wants to be carbon neutral by 2050.

"It starts with regulation," says Jason Cheng, a managing partner at Kerogen Capital, an energy-focused GP with assets in Europe. "Every listed and large company in the UK has to measure and report on carbon emissions, energy intensity and energy usage. The next step, if you assume the economies you operate in are targeting zero carbon, is a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system as currently exist in the power sector. They will be everywhere. Once everyone must offset, carbon pricing will escalate. BP is predicting $100 a ton by 2030, up from $20-30 now."

For financial investors, patchwork regulation crystallized into a coordinated sector approach with the launch of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) in 2015 and the release of recommendations for voluntary climate reporting two years later. Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) introduced TCFD-aligned indicators to its reporting framework in 2018. This year it became mandatory for PRI signatories to report on climate indicators.

Within Asia, several stock exchanges have ESG reporting and comply-or-explain policies that include climate change. A couple of months ago, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) went one step further, issuing proposed guidelines for asset managers – including locally licensed private equity firms – on evaluating environmental risk. The guidelines call for the integration of environmental considerations into strategy, engagement with investee companies, scenario analysis to evaluate portfolio resilience in different circumstances, and mechanisms for regular review and disclosure.

"Leading corporates have adopted some of the science-based targets, like complying with 1.5-degree temperature increase, and we are starting to see some financial firms do it too, mainly banks. Very few PE firms are doing it, but I think we will see more," says Coller's Black.

He is an advocate of using regulation to drive change, but it will take time to get there. When Black entered the private equity industry in 2008, carbon footprinting was largely limited to direct emissions, known as scope one emissions, where portfolio companies had clear visibility. Scope two – emissions from purchased energy – were sometimes included. Scope three, which involves tracking indirect emissions through the supply chain, was a step too far.

PAI is among the more advanced European GPs on climate change, having started measuring its full carbon footprint in 2016. However, it only became confident in the datasets last year. The initial mistake was getting too granular. Portfolio companies were asked to provide data across 50 indicators, which resulted in climate fatigue and a failure to build awareness within management teams. PAI now focuses on 10-15 indicators sufficient for an 80% materiality threshold.

When EQT launched its portfolio carbon footprinting initiative in 2015, few companies were able to submit the required numbers. This sparked a debate between manager and management teams as to whether such a data-intensive exercise was worthwhile. EQT took the analysis up a level with an environmental impact profiling tool that looked at carbon emissions, water usage and waste by industry. On this basis, the emissions intensity of the portfolio was low compared to global norms.

"This led us to evaluate where we needed to intensify our efforts in terms of data. The question became: What are other owner and company actions we should consider when addressing issues that make a real impact rather than focusing on reporting?" explains Therése Lennehag, head of sustainability at EQT. "You need to be constantly aware of the balance between the resources you have and what will make a positive impact - from a financial perspective as well as contributing to the climate mitigation and adaptation agenda."

The private equity firm completed its own carbon footprint before asking investee companies to do the same. Its first footprint including portfolio emissions is likely to be limited to scope one and two, given concerns about whether scope three data is consistent and comparable.

Starr of Carlyle is also wary of troubling companies for KPIs that ultimately might not be put to constructive use. For example, the private equity firm is an investor in Jeanologia, a Spain-based denim manufacturer with a production technology that requires less water and chemicals than its peers. These KPIs are prized above all others because they help the company reduce costs, sell into markets where consumers value sustainability.

Hypothetical scenarios

This notion of reporting for reporting's sake suggests an ongoing tension between GPs and regulators over what is materially important and what is a box-checking exercise. Nevertheless, Kerogen will call on its auditor this year to assist with TCFD compliance, slightly daunted by the 50-page documents published by listed companies. In addition to carbon emissions, the firm must consider those longer-term climate risks that stem from weather and water.

"If your assets are in a coastal area with the potential for rising seawater or extreme weather, you must show what you've done to understand, mitigate or insure against those risks," says Cheng. "Offshore oil and gas platforms account for the 30-year wave height, the 100-year wave height, and structural integrity. We will look at all those things again under different climate scenarios. It's a lot of additional work and there is a cost to that."

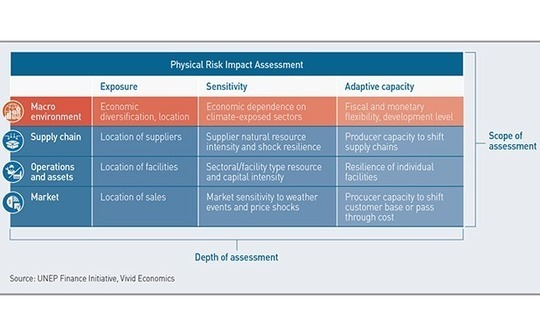

Running a scenario analysis for a 2-degree temperature increase is essentially a stress-test of a company's business model, physical locations, and supply chain under likely weather events, resource shortages and social and political circumstances. It is underpinned by the same meteorological data and climate models used by the insurance industry. Producing the final risk heatmap can cost EUR10,000-30,000 ($12,000-35,000), according to PAI's Gomez.

In theory, cost should be no object: like many ESG-related initiatives, a PE firm can make the money back through efficiencies. In practice, smaller GPs might claim they cannot justify the outlay, especially if their LPs are not asking about it. Other deterrents include a lack of ESG professionals close to portfolio companies, a cultural reticence to act unless required to do so, and concerns that a shift in the regulatory landscape could render results meaningless.

Moreover, some managers might not see the relevance. "You are building scenarios of what is going to happen in the future, but maybe they don't matter because you will be exiting in 3-5 years. And if you get the report and see the results, what are you going to do? Dump the asset? With public equities it's easier, you reweight the portfolio. With private equity, you are stuck with the asset," says Tan of China Water Risk.

But failing to act could ultimately be damaging. Industry participants observe that strategic buyers often ask more questions about the mitigation of climate risks than carbon emissions. And then there is the possibility of a single environmental lapse escalating into a serious problem – such as when a carbon black producer let slip to Coller's Black that its raw materials included peat.

"They said it was only used for one product and wasn't financially material, but it was a major problem from an environmental and climate perspective," he recalls. "Other issues come out when you start to get under the skin of companies, such as poor governance, but at least the PE model allows you to have those granular conversations."

Aside from such fears of the unknown, the driving force behind this evolution in ESG best practice will be the needs of LPs who hold the purse strings. This dynamic is already playing out in public markets between companies and shareholders.

"We are seeing both the breadth of data disclosed across the market and the consistency and the quality of data get better," observes Richard Manley, head of sustainable investing at Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB). "Companies have woken up to the fact that the inability to articulate performance on key areas of ESG is going to result in difficult conversations with key stakeholders, as well as shareholders."

CASE STUDY: The oil and gas investor

Kerogen Capital, a Hong Kong-headquartered private equity firm specializing in international energy investments, has prioritized environment, social and governance (ESG) considerations since inception. Coal was dropped from the strategy for climate change reasons in 2011. Membership of the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) came in 2014, followed by an ESG policy statement and regular reporting to LPs.

"Before all that, it was still kind of there," notes Jason Cheng, a co-founder and managing partner at the firm. "In oil and gas, health and safety and environmental impact are part of standard operating procedures because they are regulated. It just wasn't in a structured reporting format for our LPs, so we focused on that quite early."

Kerogen, which has approximately $2 billion under management across two funds, provides development capital to established junior oil and gas companies. The Fund II portfolio is Europe-heavy, with a hit of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. In the last three years, these companies have been examined through a climate change impact lens, with the implications of carbon-light and low break-even strategies considered, among others.

Low break-even essentially means more buffer. "It's all about long-term climate change and stranded assets. If your asset breaks even at $100 a barrel but the long-run oil price is $60 a barrel due to a 2-degree Celsius policy change and that caps the amount of oil and gas you consume, you don't want it on your books," says Cheng.

Kerogen can chop and change strategy according to where it sees opportunities and risks. Renewable energy has always been an option, but the team wasn't comfortable with the returns, preferring to concentrate on carbon light oil and gas. To this end, Kerogen has formalized its exclusion list, adding assets in environmentally sensitive areas like the Arctic and the mining of tar sands or other emissions-heavy projects that don't allow carbon capture.

Data-driven analytical are likely to become more prevalent in a climate change context as a means of driving operating efficiency with greater safety and reducing the carbon footprint.

As more countries have pledged to become carbon neutral by 2050, discussion within the oil and gas industry has turned to zero-carbon economy solutions. There is increasing interest in hydrogen, ammonia, and carbon capture and storage, where oil and gas skills and infrastructure can be used.

"The current hydrogen economy is mostly done by oil and gas and the chemicals sector – transportation, storage, utilization," says Cheng. "There is also a lot of talk in Europe about how you can repurpose the oil and gas industry, taking those existing pipelines and offshore platforms and using them to inject carbon into empty reservoirs."

Kerogen plans to start working on its carbon footprint, following the introduction of regulation in the UK requiring private companies above a certain size to report on energy use and emissions. Challenges include the proliferation of different standards.

"Where do you draw the line between direct and indirect emissions? What about control versus non-control? If you're a partner in a joint venture and someone else is the operator and not providing data, you can apply pressure, but you can't definitely get it," Cheng adds. "Now the industry is more regulated in Europe, it is easier to obtain data."

CASE STUDY: The forestry investor

New Forests, an Australia-headquartered sustainable real assets investment manager, is currently piloting scenario analysis of different climate impacts on its portfolio. Wildfire is top of mind.

"We own forest in Australia and California, and these are areas that have fire of a certain periodicity," says David Brand, the firm's CEO. He runs through three strategies to cope with it. First, insurance. New Forests is careful in optimizing its fire coverage in Australia, estimating the cost versus the loss rate. Second, diversification. Clients have diversified portfolios of forestry investments and an average loss rate they are willing to bear, so this must be factored into pricing.

Third, active management. "In Australia, for every forest fire that breaks, you have aircraft patrolling continuously. There is also initial attack equipment, like water points, placed everywhere. If a fire occurs and you can attack it in 15 minutes you can normally stop it," he explains. "A lot of effort goes into initial attack equipment, pre-positioning resources where we expect potential risk factors."

Founded in 2005, New Forests has A$5 billion ($3.6 billion) under management in sustainable timber plantations, rural land, and conservation investments related to ecosystem restoration and protection. The portfolio encompasses more than 950,000 hectares of land.

Scenario analysis has become a priority because the firm's 2020 climate disclosure report is its first to use guidelines issued by the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD). Therefore, disclosures must address the portfolio-level impact of the physical risks of climate change and the transition risks of low carbon economy. Extreme weather events, rising sea levels, pests and diseases, and adverse regulatory changes are all cited.

So are the opportunities that might emerge. This is a key area for New Forests given its emissions are negative and so exposure to the firm's funds or other products can generate offsets.

Over the next two years, New Forests wants to measure its carbon footprint and explore specific footprinting for forestry, set emissions reduction targets for portfolio companies, report on climate impact, and develop a science-based climate target for its portfolio.

Brand's career tracks that of sustainable investment. In the 1980s, he calculated carbon budgets for red pine forests in Canada. In 1999, following the Kyoto Protocol agreement, he was involved in the first carbon transaction relating to forestry. New Forests came into existence at the same time as a host of carbon funds, many of which failed, making institutional investors wary of climate finance.

"We always said it would evolve into a real asset class. In the last few years, people have been more willing to look at investments in forests and have some upside exposure to climate mitigation benefits and carbon markets," Brand says. "It's now swinging back to thinking about climate change benefits as an integral part of why you invest in forestry – looking at your entire portfolio, your emissions and removals and getting to the net zero. This forces us to invest in the sophistication of our reporting, monitoring, and accounting mechanisms."

He believes greater transparency and standardized accounting will become the norm over the next five years, while more opportunities emerge to look at climate solutions investing.

"When you have all these companies making commitments to be net zero by 2050, there is going to be a search for investment strategies that help deliver those outcomes," Brand adds. "From our perspective, what's emerging is a concept of nature-based solutions as being 25-30% of the decarbonization process between now and 2050."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.