Asia online gaming: Game on

Videogaming has outgrown entertainment and media to become a sector unto itself, with new angles for exposure multiplying rapidly. E-sports is an area to watch

When gamification first came into focus in the early 2010s, it appeared to be about capturing the attention of younger consumers and encouraging engagement by leveraging the most addictive aspects of game design. Now, the trend is more clearly interpreted as a sign that those consumers are no longer a demographic of emerging significance to be targeted opportunistically. In fact, they're not even that young anymore.

In the past decade, gamified user experiences have graduated from children's education to banking and cybersecurity, and in the process become a fixture of employment contracts. Unlocking benefits through the accumulation of points and badges is no longer limited to consumer behavior such as saving or spending certain amounts or activating an app a certain number of times; it's an accepted incentivization method in almost any context.

All this hints at a yet deeper layer of the gamification onion by revealing that gaming has become as much about lifestyle as entertainment. The best evidence for this is in the statistical disparities between gaming and the sector it left behind. The global videogame market was worth $130 billion in 2018, more than triple the size of the movie industry. Indeed, games are already worth more than music, movies, and video industries combined.

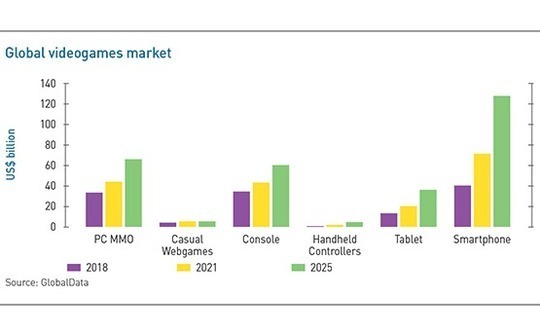

The market is expected to be worth more than $300 billion by 2025, according to GlobalData, and most of that growth will be in Asia Pacific. At present, the region accounts for 52% of the global market; China leads the way with annual revenues around $35 billion. Statistica expects China online gaming revenues to hit $46 billion next year.

A cultural coming-of-age is not the only factor driving growth. The move online has made gaming more accessible globally, and in the rapidly digitizing markets of Asia, made it a daily routine for millions of people for the first time. Smart phones were the largest platform market in 2018 at $41 billion. That figure is expected to reach $128 billion in 2025.

"This used to be a niche, but a big game launch can make as much money as a blockbuster film and engage as many, if not more, people," says Ed Thomas, research director for thematic research at GlobalData. "But the reason it's being taken more seriously is that the core fan group has aged into the mainstream. They're changing the way we perceive gaming and the way it's discussed in the media."

The specialists

In venture capital, this process is being played out in the emergence of specialized gaming accelerators and fund management teams as well as an increasing population of longtime gamers in the decision-making echelons of generalist GPs.

Winston Adi, the millennial-aged head of investments at Indonesia's MDI Ventures, offers a case in point. He describes the investment opportunity as divided into two fundamental risk-return profiles: competitive games that are able to support myriad tangential businesses for a devoted consumer base; and casual-interest games that offer potential for a runway mass-market hit but at the cost of poor user retention and an exceptionally high failure rate.

"Competitive games have a lot more stability than casual, but they're harder to tap into for game developers," Adi says. "VCs therefore have to look for other approaches on the enabler side like payments, championships, and other ways of generating revenues. There's a lot of that going on in Asia, and it's creating a whole new industry. We are going to see more e-sports players becoming public figures and grand prizes at events becoming larger."

MDI's standout gambit in this line of thinking is Mobile Premier League (MPL), an Indian e-sports platform also backed by Sequoia Capital India. MPL provides competitive gamers with a forum for finding and facing off against online opponents in more than 40 games, including the popular combat game "Free Fire." This fills demand for competitive play and potential to win real cash prizes without the risk of backing specific titles or development studios.

The platform-for-gamers concept has proven popular with generalist investors because it blurs the lines between gaming and the arguably more familiar territory of social media. Joy Capital demonstrated this effect in May by leading an approximately $40 million Series B round for Reworld, a Chinese platform that allows amateur programmers to design and share their own games

Reworld doesn't consider itself a gaming company per se, although its users are all gamers and the company's fortunes are tied to those of the gaming industry. Co-founder Guangshi Yao is augmenting this upside through technology developments to make the game-building tools more intuitive to first-time users, as well as potential partnerships with educational institutions that could incorporate the platform into their curricula.

"We are expecting pretty extensive market expansion because user-generated content creates a cycle of growth for developers and consumers by being both creative and social," Yao says. "People are building a community by designing games that show their own personalities – we actually didn't expect that kind of activity. In 3-5 years, there could be hundreds of millions of users on the Reworld platform."

Where's the money?

The idea of hundreds of millions of socially connected gamers helps illustrate the gaming-as-a-lifestyle thesis, but like many internet-powered phenomena, it also raises questions about monetization.

In online gaming, freemium models have proven the most popular to date. These play well with its addictive qualities, especially in Asia, where mobile gaming is disproportionately popular and developing economies respond well to no-cost adoption options.

Paid features in this model include currencies that allow players to advance their progress within the game (mostly used in casual games) and exclusive content such as custom costumes for game characters (mostly used in competitive games). Depending on the market, game genre, and player behavior for that genre, advertising could play a greater role in driving revenue.

"Having a game with a strong core gameplay that keeps players coming back is fundamental, followed by a meta game that encourages players to monetize whether through in-app purchases or ads, or even through referrals," says Phylicia Koh, an analyst at Play Ventures, a gaming-focused investor based in the US and Singapore.

"These also need to be complemented by a strong practice of data-driven user acquisition; the team should understand metrics like eCPMs [effective cost per mille], payback period, lifetime value, and the levers that are at their disposal."

Play Ventures is active globally and within Asia maintains a focus on Southeast Asia and India, which the firm estimates as $4.4 billion and $1.1 billion markets, respectively. "Both markets also have pools of good, affordable development talent that can help a company move and ship games fast, and with a cost and runway advantage," Koh adds.

The VC firm's portfolio includes Vietnam's Gamejam, a casual game developer with 50 million downloads, and Mod.io, an Australia-based cross-platform user-generated content service for game studios. Earlier this year, it backed Singapore's Potato Play, a publishing and marketing specialist that helps game developers with cross-border expansion.

Southeast Asia and India are also seen as benefiting from the most dramatic technology leapfrogging effects and the youngest populations – key themes in the mobile gaming equation. These currents have underpinned a groundswell of specialist investment and industry development in recent years seeking to blend gaming with the connectivity and financial technology themes driving adjacent sectors.

Galaxy Ventures, a Thai investor spun out of local game studio Ini3 Digital, is firmly rooted in this concept. The plan is to leverage 15 years of gamer behavior data accumulation at Ini3 and translate that into insights for Galaxy investments in e-commerce. SoftBank Ventures Asia acquired a 23% stake in Ini3 in 2014 and exited late last year. Galaxy has made two gaming investments but intends to focus primarily on e-commerce related companies.

"The trends of games and e-commerce are pretty correlated," says Pattera Apithanakoon, founder of Galaxy and CEO of Ini3. "All gamers are e-commerce users, and they do a lot more e-commerce than non-gamers because they're so used to online behavior. During the home quarantine periods of COVID-19, e-commerce and gaming both accelerated in revenue and daily active users."

Big hitters

China, Japan, and Korea remain Asia's largest gaming markets by far, however, and the only three in the region that break the top 10 globally.

China is also notable as one of the few markets in the region to see large deals. Notably, these include US private equity firm Platinum Fortune acquiring China-owned and UK-based developer Jagex for $530 million in May. Perhaps the biggest deal in this space happened in 2017, with Jinke Entertainment Culture buying game maker Outfit7 for $1 billion.

This dominance will be supported by the advent of cloud and virtual reality-based gaming, which are expected to be gain better traction in China. As cloud gaming matures in the more foreseeable future, it is expected to drive creative business modeling by erasing the longstanding idea that a game is tethered to a particular device.

The main deterrent on gaming growth in China will be the general opaqueness of the market. Owen Soh, founder of EastLab Consulting, a firm that helps foreign game developers enter China, estimates that only 10-15 of the top-100 grossing US games make it to China. Regulation, heavy upfront costs, and challenges around securing quality partners in the traditional way of attending conferences and trade fairs are the main obstacles.

"While there are a lot of great publishers in China, there's a lot of guesswork and information disparity in the old-school way of meeting them," Soh says. "You don't really know if they are any good, and that either scares developers off or gets them involved in bad deals. There's a lot of work in the negotiating and triangulating data points on the ground. You have to figure out what's real, what's not, and which guy can you trust."

The key regulatory issue here is the ISBN licensing regime for cultural and media imports. ISBN omitted videogames until 2016, and implementation and enforcement has been choppy. Games offered via Android channels – which traditionally represent 70-80% of the local market – fell in line early. Apple, by contrast, has enjoyed a loophole that allowed developers to sidestep the censorship. That is coming to an end next month.

From an investor perspective, the purge of Apple games – many of which will re-list in China after applying for an ISBN – represents an interesting opportunity. The sudden disappearance of some 8,000 games is expected to spike demand for the remaining titles and create openings for new ones to fill the void.

This kind of resilience in the face of a regulatory crackdown says much about the sturdiness of gaming demand, especially in the COVID-19 era. There has been no shortage of tough-luck stories about game launch delays during the pandemic from major players like Sony, Ubisoft, and Square Enix. But all anecdotal evidence suggests gaming is virtually recession-proof.

"It all sounds daunting, but the demand for gaming products is here, and it's quite inelastic," Soh adds, balancing the difficulty of entering China with the size of the opportunity. "It doesn't matter if times are good or bad, people are going to continue to play."

This sporting life

E-sports has possibly been the hardest hit area during COVID-19 due to its reliance on stadium-based events. There is a significant amount of broadcasting in the industry, but true to the model of traditional sports, all matches are played in stadiums, and around 60% of industry revenue is generated from brand sponsorships around these physical events.

Rupantar Guha, a senior analyst at GlobalData focused on gaming, remains bullish on e-sports in the long term, however, noting that it already caters to 10% of the global online population. This is despite estimates that e-sports account for only 1% of the overall $200 billion sports market. E-sports may also be the best reminder of the cultural gravity that is pushing gaming to transcend its entertainment and media roots as an industry.

"People who grew up watching e-sports will continue to be regular viewers in the coming years," Guha says. "There's also going to be more people watching games online and offline. The trend of traditional sports organizations running virtual events – NBA, NFL, F1 and NASCAR – has been happening for 3-4 years and COVID-19 has only accelerated it. We're going to see more of that in the next 2-3 years, and it will only help e-sports to grow."

North Asia has proven an early leader in this area as well. Jamie Park, CEO and founder of Seoul-based e-sports investor ATU Partners estimates that 70% of the top players globally are from Korea and that the country is in a unique position to leverage the Korean wave cultural phenomenon to popularize local teams and e-sports generally.

This is precisely the plan for ATU's debut fund, which was set up last year with a $17 million corpus that has been fully deployed in three investments. These include AZYT, a US-based e-sports talent agency, Proguides, a US e-sports coaching platform, and DRX, one of Korea's premier e-sports teams. LPs included Kibo Steel, Park's family business, Woori Technology Investment, SB Partners, and Kakao Games.

Prior to raising the fund, Park spent two years leading global business development for e-sports broadcaster OGN, where he hatched a plan to connect the US and Korean ecosystems. Rather than replicating the OGN model – Park considers e-sports broadcasting unsustainable as a business – the approach will be based on team branding. Team-level sponsorships with the likes of Redbull and Kakao will drive most of the revenue, with significant contributions from goods such as jerseys and bags with the DRX logo.

There's reason to believe this strategy could develop into a discrete private equity and venture capital theme. DRX is only the third most popular team in its "League of Legends" tournaments, yet is able to sell out fan meet-and-greets at $250 a ticket. Park says 85% of the team's viewership is already outside of Korea. The company received $10 million in funding this month to pump up these numbers, bringing on Bae Yong Joon, a popular K-drama actor, as the campaign's cultural ambassador.

"E-sports has more potential than K-pop, K-beauty, or K-drama because this is sports, so there's no language barrier," Park explains. "Age is also important. The average viewer is 26-27, while for traditional sports, it's 54. Traditional sports are 80% consumed through TV, and e-sports is 80% digital. Sponsorship-wise and media-wise, why spend money on 54 and 80% TV? E-sports is clearly the next sport for millennials and Gen Z. Teenagers don't watch baseball and the Super Bowl anymore."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.