Corporate VC in Asia: Moment of truth

Cutting non-core operations is the standard corporate response to an economic downturn. Companies in Asia must decide whether the long-term benefits of exposure to new technologies outweighs short-term pain

Dataxet completed the acquisition of Indonesia-based Sonar Platform last week, adding another strand to its Southeast Asia data intelligence network. It also represented an eighth exit for MDI Ventures. Launched by Telkom Indonesia in 2014 with a general idea to invest in the vendor ecosystem, the corporate venture capital unit has emerged as a valuable contributor to its parent's bottom line.

"A lot of people at Telkom thought MDI was a waste of time, an experimental model – good to have because everyone else had it. But when we realized our liquidity events in 2019 and booked a profit of more than $50 million through those capital gains, they saw it as a model that works," says Nicko Widjaja, who finished his four-year tenure as CEO of MDI last August. "VC as a business is now huge for Telkom, and MDI is about to announce its fourth fund. SoftBank is a telco that declared itself an investment company. Telkom might think it is doing the same thing."

Widjaja is now looking to recreate some of this magic under the umbrella of another state-owned enterprise, heading up Bank Rakyat Indonesia's BRI Ventures. It recently launched an onshore fund that will include contributions from third-party investors and take BRI beyond its financial technology comfort zone into areas ranging from education and transportation to healthcare and retail. At the very least, portfolio start-ups will be encouraged to use the parent company's digital banking infrastructure.

Although Widjaja observes that other Indonesian groups are building their own versions of MDI, the model remains a work in progress. The same can be said for much of the rest of Asia. A clear majority of corporate venture capital units in the region operate under purely strategic rather than financial mandates – desired, in many cases, because developed market peers have them – and they are structured and staffed accordingly. Balance sheet vehicles are more common than GP-LP structures; carried interest is a rarity; and employee turnover is a challenge.

All this points to a chronic short-termism that might be brutally exposed in the event of a protracted post-coronavirus economic downturn. Whenever a company's core business takes a hit, energy and resources are directed to treating the wounds. Non-core operations – including VC units – are deprioritized, perhaps even terminated. This scenario will play out again over the next 12 months, but how widely? Corporates that fear the long-term ramifications of technology disruption more than the pressures of short-term commercial dislocation might see the benefits of staying involved.

"They do pull back in downturns, but what is different from 2000 and 2008 is that corporate venture capital is now a must-have, not a nice-to-have," says Eddy Chan, founding partner of Intudo Ventures, an Indonesia-focused independent VC firm that counts 25 local family-owned conglomerates as LPs. "I've never seen corporates so willing to adopt technology and partner with our portfolio companies."

Appetite for disruption

There is a difference between engaging with start-ups in order to support core business operations and making direct investments in these companies. Similarly, a willingness to consider technological applications should not be confused with actively deploying capital in them. However, there is no question that corporate venture capital activity in Asia has grown exponentially in recent years.

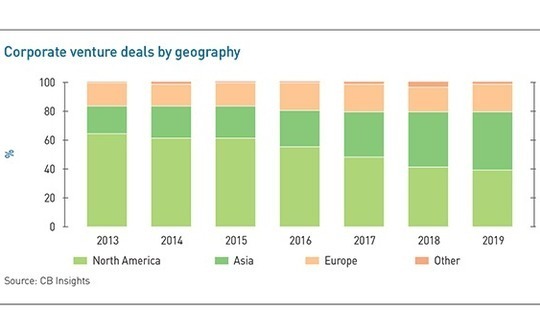

In 2019, Asia surpassed North America as the most active market for the first time, accounting for 40% of the 3,234 deals announced globally that featured corporate investors, according to CB Insights. The amount of capital that went into Asia-based transactions actually fell 20% year-on-year to $15.9 billion, largely due to a drop-off in China. It is likely no coincidence that late-stage funding rounds in the country's consumer internet space also declined. Japan and India, meanwhile, continued to see growth. Japan alone contributed more than 400 deals.

"I do see some scaling back by corporations because by nature they have a second reflex of flight to safe harbor. I have seen situations where corporates were supposed to invest but they've backed out, and because we like the assets and we are not so much attached to the hip as others, we have invested more than we planned," says Sae-min Ahn, a managing partner at Rakuten Ventures, the corporate VC arm of the eponymous Japanese e-commerce giant.

Appetite varies by industry, although there is not necessarily a perfect correlation between COVID-19 impact and level of investment activity. Oil prices are down about one-third for 2019 to-date, but Xin Ma, a managing director for the Asia platform at Total Carbon Neutrality Ventures, reports that her budget is unchanged. Parent company Total announced in May that it wanted to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, so the VC unit continues to ramp up exposure in areas such as renewable energy, smart energy, mobility, and carbon neutrality.

Tokyo Disneyland reopened last week after a four-month closure, but this didn't stop operator Oriental Land unveiling a JPY3 billion ($27 million) corporate venture vehicle in June. Oriental Land Innovations will target investments that help its parent address existing problems and prepare for the future.

Necessary evolution

Broadly speaking, adoption of corporate venture capital has tracked the widening scope of technological disruption. First telecom operators and media companies, then banks. William Bao Bean, a general partner at SOSV who previously worked for SoftBank and SingTel Innov8, suggests that pharmaceuticals could be next. Super apps pursued by the likes of Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings have already disrupted the direct relationship between consumer product brands and customers, and they are taking on financial services. These companies' healthcare units could try something similar.

"Alibaba and Tencent have all the patient data, they have the distribution, and they have unlimited cash. Most drug companies don't create drugs any longer – they are M&A teams attached to supply chains and distribution," says Bao Bean. "Alibaba and Tencent have everything and they have invested in a lot of pharma VC funds as well [giving them exposure to drug development start-ups]. All they need to do is get teams in-house and big pharma could have all sorts of difficulties."

Some companies are looking to counteract this through initiatives of their own. Sanofi worked with SOSV on a pilot accelerator program in China last year and the pharmaceutical player is expected to serve as anchor LP in a smart healthcare fund to be launched by Cathay Capital in the country. It represents a more focused, and renminbi-denominated, complement to the private equity firm's existing innovation fund series.

Mingpo Cai, founder and president of Cathay Capital, notes that Sanofi built a global PR campaign around its earlier commitment to the innovation fund. He believes this underlines the company's desire to understand how digitization is shaping healthcare and come up with a strategy that meets the needs of a younger demographic while being highly focused on services for patients.

While healthcare disruption has yet to be fully mapped out, retailers are already seeing what technology is doing to their business. When asked to identify which sectors are best represented among the corporates reaching out to them in search of knowledge sharing or collaboration opportunities, independent venture capital players give long and varied lists. However, retailers are a consistent presence, the implication being that COVID-19 is forcing them to be more proactive about digitization.

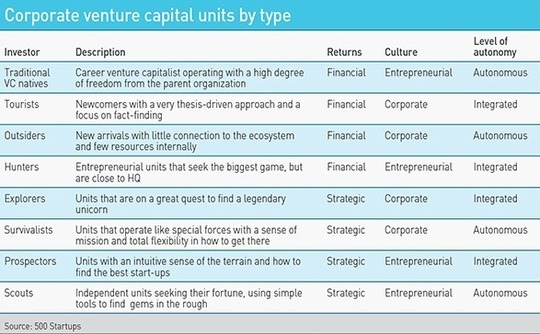

Khailee Ng, a Southeast Asia-based managing partner at 500 Startups, places corporates into four categories based on their willingness to engage. Each end of the spectrum is populated by companies that have no interest in corporate venture capital: one group faces an existential threat and they are simply fighting to survive; the other comprises businesses that are benefiting from COVID-19 – manufacturers of personal protection equipment, for example – and fighting to keep up with demand.

In between are companies that feel they must take action to stay ahead of the technology curve, and safeguard their futures, by acquiring or collaborating with start-ups. They share the middle ground with businesses that haven't been badly impacted by COVID-19 and have strong cash positions. Some are proactive in terms of innovation while others are not.

"More corporates want to talk about innovation and building resilience into their supply chains, creating an on-demand workforce, and finding new ideas," Ng adds. "They haven't acquired a bunch of start-ups, but they want to talk about it. In the past week I've had three calls with large corporations about collaboration and exploration. These could be precursors to partnership and transaction, but we haven't seen much transaction yet."

Mixed bag

Engagement, when it happens, can come in many different forms. The SOSV pilot accelerator programs – which have been set up for the likes of Unilever, Johnson & Johnson, and ABInBev – are predicated on synergies rather than financial returns. "The money doesn't come from the CFO, the goal isn't to drive IRR," Bao Bean says, adding that identifying and investing in a portfolio of start-ups is far removed from the management of internal politics integral to bringing external technologies to internal business units.

The emphasis is on learning from adjacent businesses that can make the parent's core operation more effective, rather than bundles of commercial agreements between start-ups and extraneous subsidiaries. SOSV ensures its partners remain committed by requesting payment before launch and holding them to an agreed timetable. The financial undertaking represents a rounding error for most corporates, but if they are unable to modify accounting practices to commit cash upfront then they probably aren't ready for innovation. Internal buy-in is essential.

The latter sentiment is echoed by Christian Noske, head of Alliance Ventures, an investment unit established two years ago by Nissan Motor, Mitsubishi Motors, and Renault, but that is largely where the similarities end. While recognizing the need for financial and synergistic goals, he insists the financial component must be there if a program is to achieve long-term viability. Moreover, half the Alliance team concentrates on commercial deals – of different kinds – that bind start-ups to the parent.

Earlier in his career, Noske spent about four years guiding BMW's corporate venture program to a GP-LP structure that was unique within the automotive sector at the time. He was one of four partners that made investment decisions. Likewise, moving to Alliance, a GP-LP structure was a long-term objective, not a realistic immediate goal. Nissan, Mitsubishi and Renault wanted direct oversight with a three-person investment committee comprising the companies' CEOs.

"For me to join a more corporate structure, I didn't see how it could be successful without CEO-level involvement," he says. "If it's the CFO, that doesn't work long term or even medium term. If it's the CTO then that person must be a business-type, not an engineer-type, or the structure won't be right."

However, Ahn still finds himself telling stories on all fronts, constantly educating colleagues from different parts of Rakuten on what venture capital does and why helping specific portfolio companies can benefit the parent. It is a familiar refrain from industry participants, sung with no small degree of frustration by those who deal with ever-changing executive line-ups. Japan is a case in point.

"It is difficult for Japanese to execute corporate venture capital programs because they normally get moved after 3-5 years. Investments require 10-12 years, so you can't get quick results," says Shinichiro Hori, CEO of YJ Capital, the corporate VC unit of Yahoo Japan. "Normally, when a new CEO comes in, they check all the financial results and ask why the fund hasn't delivered any profit in three years. Then they say it should stop." Nevertheless, he adds that the surge in corporate venture launches in recent years has yet to prompt a consequent spike in closures.

There is an historical trend across multiple markets whereby the initial excitement around investment wears off and is replaced by cold-eyed acknowledgment that a program is not delivering enough benefit to justify the time and resources spent on it. In-house operations are shelved in favor of outsourced accelerator programs or commitments to third-party venture capital funds. Corporates have less investment autonomy, but they can still gather information and establish partnerships with start-ups.

The mismatch in expectations can extend to situations where parent groups have expressed interest in acquiring start-ups after getting to know them through VC investment. "When we told Telkom that a company was ready for exit, in their minds there was still another five or six years to assess the company and the sector. We had invested in the Series B and C and sometimes exits would come after Series D," says BRI's Widjaja. "They need to fix the speed of learning – an organization must be flat."

A 500 Startups survey of more than 100 corporate VC units across 35 countries identified four major challenges for these groups. Three relate to time: securing timely internal sponsorship and approval for investments; running timely pilots and proof of concepts around deals; and maintaining the parent organization's long-term commitment to investing activities.

Cultural question

This raises the issue of cultural incompatibility between VC and traditional corporates. According to Ahn, the problem percolates into recruitment policies at these VC units. A successful investment professional working for an independent firm typically offers a combination of domain expertise, industry networks, and hard graft. These qualities are not necessarily recognized within a corporate structure.

"Many people get these jobs because they have the trust of the CEO; they have corporate and political capital inside the company," he says. "The issue with corporate investment is it is often seen as a privilege: ‘I've bled for this company for 20 years, now I have the authority to use some capital to look at my aspirations and manifest that into investments.' You get enough juice inside the corporation and you can make these bets. It has morphed into people trying to do that for corporate venture capital."

Ultimately, companies attract the people that their commitment to the asset class and their compensation policies deserve. BMW Ventures was unusual for its time in structuring carried interest in the traditional VC way; Alliance Ventures, given the absence of a GP-LP structure, is forced to be creative, awarding long-term incentives based on financial performance. Of the Asia-based corporate VCs that spoke to AVCJ, most do not offer carry; and those that do cap the upside. This has obvious implications for talent retention and the financial performance of programs.

"If the compensation is not success-driven, if incentives are not aligned, there will be less investment activity. Why would you bother swinging the bat if you are not adequately compensated for taking the risk?" says Intudo's Chan. "You never lose money on an investment you never make."

One solution is to raise capital from third-party investors, either through a joint venture or a commercial fund structure. In this way, the VC unit is not entirely beholden to the will of the parent, which makes it harder to unilaterally withdraw money from programs and easier to justify paying market-rate salaries. Some groups in Asia are taking this approach – although there have been situations in which it is driven more by the parent wanting to commit less capital than a desire to commercialize operations.

The importance of technology is not lost on Asian corporates, but it remains to be seen whether this means captive VC units are elevated from non-core to core status. Maybe this time it really is different.

"When times are good, everyone is all about innovation and start-ups; when times are bad, anything non-core goes out the window. That's been the rule of thumb since corporate VC started," says Bao Bean of SOSV. "But many businesses that took this attitude in the past are no longer with us. The average lifespan of a company on the S&P 500 has fallen from 30 years in the 1990s to less than 20 years. If you are not continually innovating, you aren't going to survive."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.