Retail investment in PE: Common stock

Signs are converging that increased retail investor participation in private equity is inevitable. Myriad roadblocks around access, alignment, and infrastructure will inhibit the transition

A dizzying array of overlapping trends has complicated private equity in recent years, including increasing requirements around environmental, social and governance; more complex GP-LP relationships and multi-strategy structures; rising levels of dry powder and snowballing valuations; and a growing reliance on data and technology.

All this can be simplified, however, into a single observation: the industry is getting bigger and therefore more inclusive, and therefore more standardized.

By most accounts, the endgame in this trajectory is a democratization of private equity through the creation of an industry that includes mass participation by retail investors and blurs the lines between public and private market processes. Stakeholders with the widest field of vision, including global investors, regulators, and industry associations, have been instinctively directing this evolution for years. Now, they're beginning to articulate their expectations.

In December, the US Securities & Exchange Commission proposed several changes to its definition of a professional investor with a view to improving Main Street investor access to private markets. This included the establishment of an asset management advisory committee, which has fielded perspectives from some of the leading names advancing the retail agenda from the GP side, including The Blackstone Group and Apollo Global Management.

Although optimistic, the proceedings have been colored by a sense that there is something mutually incompatible about retail investors and private equity. The idea of bringing an emotionally charged investor base accustomed to a perceived level playing field in terms of information availability into an illiquid asset class known for proprietary insights and a relatively dispassionate approach to long horizons is seen as forcing a round peg into a square hole.

As a result, experimentation has been cautious and even the staunchest proponents are treading lightly. "We have absolutely no interest of an expansion unless it's done right," John Finley, a senior managing director and chief legal officer at Blackstone told the committee in January. "Not only would it not be good for the investors, it wouldn't be good for Blackstone, and it wouldn't be good for the industry. So we think this does need to be done carefully."

Demand and supply

For investors like Blackstone and Apollo, tapping the retail market is partly framed by agendas around opening opportunities to the broader population or innovating infrastructure for the less developed ends of the deal pipeline and overall ecosystem. For smaller GPs, the incentives are more direct. Institutional LPs scaling back their manager relationships as data sharing becomes more involved is often cited as a contributing factor. The motivation is arguably greatest for first-time managers and those planning to finance an evolution from a regional to global status.

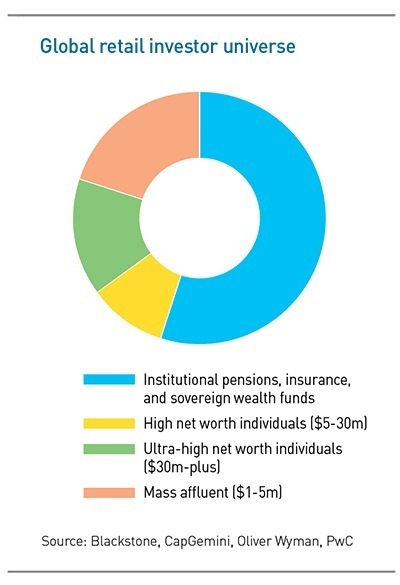

Still, even the heavyweights have found the mountain of retail money impossible to ignore. Citing data from CapGemini, PwC, Oliver Wyman, and Cerulli Associates, Blackstone has tallied the global retail market at $68 trillion, versus an $84 trillion market for pensions, insurance companies and sovereigns. About $30 trillion of the retail space is in the mass affluent category. These are people with personal wealth in the range of $1-5 million, below the threshold that typically defines high net worth individuals.

There is no consensus on how the coronavirus-linked disruptions in public markets will impact demand for private equity from retail investors in the immediate term. With public markets valuations appearing more attractive as uncertainty mounts, there could be a doubling down on the most liquid assets. Conversely, the emotional rollercoaster on display has been interpreted as convincing publicity for private equity's relative stability.

Regardless of any relatively short-term macro fluctuations, Asia is expected to be the main beneficiary of increased retail participation in private equity. In addition to being flush with first-time fund managers as well as a spattering of regional players nurturing global aspirations, Asia benefits from the fastest growing middle-class demographics globally. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development, Asia will account for 85% of the growth of the global middle class between 2020 and 2030.

For private equity firms in the region, optimism around tapping this resource in a fundraising context remains tempered by a question of resources. Even Asia's largest pan-regional operators are not seen as having sufficient in-house resources to manage the high volumes of LPs that would come with a mainstream retail program.

Technology solutions

Solutions are beginning to emerge in the form of technology-enabled platforms that pool retail capital for combined fund commitments. In Singapore, these instruments – often online exchanges or special purpose vehicles – have come to represent up to 10% of the corpus for some smaller funds. Caroline Baker, a Singapore-based managing director at fund administrator Vistra, is currently tracking at least five such vehicles but suspects there are considerably more.

"Compared to two years ago, we're definitely seeing an increase in the amount of retail investors being interested in private equity, and we're seeing more and more sophisticated platforms where they can pool their capital to invest," Baker says. "So I think there will continue to be more retail investors looking at ways to access this market and more first-time GPs being open to having retail investors access their funds, but I don't think it's going to turn the industry on its head. It's going to be a slow and steady growth."

Much of this growth has been inspired by Temasek Holdings, which has championed the retail-in-PE concept in recent years through Azalea Asset Management, a wholly-owned subsidiary that has an independent board and management. Azalea has floated three products under its Azalea series, which offers variously rated and publicly listed bonds backed by securitized secondary interests in a portfolio of PE funds.

Retail participation has been enthusiastic, with anecdotes of subscriptions via ATM as low as S$200,000 ($70,000) and prospectus handouts at pop-up tents testifying to the street-level penetration of a campaign to educate everyday investors about private equity. Mass affluent participants in Astrea products only receive returns from the bond interest, however, not equity returns. Azalea's first attempt at a direct equity offering for retail investors came in December with the launch of Altrium Private Equity Fund I.

"When we brought Altrium to the market, people understood the quality of GPs like Blackstone, KKR and EQT, which are not natural household names," says Margaret Lui, CEO of Azalea. "Over time, we're going to take that familiarity from high net worth investors to the man and woman in the street, hopefully with a retirement product. That product will need some tweaking because at the end of the day, obstacles to individuals participating in PE such as illiquidity and long holding periods can't really be changed if you want PE-style returns. That will be for us to figure out down the road."

Trends around online crowdfunding and cryptographic tokenization are expected to accelerate retail activity in private equity by eliminating the costs and operations burdens associated with mass distributions and low denominations. To some extent, this could also discharge GPs of difficult decision-making about how high to set their minimum contribution limits, but it would also ramp up the urgency around calls for a cultural change in terms of information sharing.

"If a technology platform can bring the costs of distribution down for managers, they are quite open to explore how they may distribute their funds to the mass affluent through such platforms, so there would be good potential for that market gaining access to private equity," says En Yaw Chue, a managing director at Azalea. "The question is, how far are the managers willing to disclose their performances and data on underlying companies. We've seen improvements in the willingness to disclose, but more granular information may be needed for everyday retail investors."

Investor protections

This view offers a reminder that a dramatic opening of private equity to retail investors – whether through technological workarounds, regulatory clearances or a combination of both – would entail significant dangers. Even with enhanced disclosure regimes, PE will remain an uncomfortably opaque asset class for investors accustomed to evaluating companies based on accessible financial metrics. When retail investors do receive the required information, they may have little capacity to properly process and analyze it.

There are also concerns around the idea that private equity markets globally are already contending with growing levels of dry powder and that a retail influx could exacerbate the problem. The idea is that any further increase in competition for deals would drive up valuations and lower returns on exit.

At the same time, an oversaturated market would increase competition among LPs for fund allocations. Effective manager selection is seen as particularly important since returns are disproportionately influenced by top-tier funds. For many institutional investors, it is already considered difficult to get into the best funds. For individuals, it would be nearly impossible.

An oversupply of capital also leaves LPs in a weaker negotiating position on terms. The concern is that retail investors in particular will be ill equipped to secure satisfactory protections and rights on fiduciary duties, especially given that even institutional LPs continue to struggle on these points. Even when an institutional LP uses its bargaining power effectively, it will not necessarily tickle down to the retail investors, who will be obliged to negotiate separately.

Requirements for funds with retail investors to have a material institutional component could relieve some pressures around manager selection since these funds will have been validated by institutional due diligence. But this will not solve for issues around fiduciary protections, nor does it reduce retail investors' naturally higher likelihood to default on capital calls.

The Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA) has been the most vocal in recommending solutions for these issues, especially in the form of government oversight. It advises that GP-LP agreements be standardized in terms of contract type and the definitions of key terms and that retail investors be required to pass an examination proving investment competence. This would encompass themes around illiquidity risk, the skills needed to evaluate a PE team and its track record, as well as the importance of fee reporting.

Other submissions have suggested that GPs with retail investors provide full fee disclosures in a retail format, including expenses offset or charged to portfolio companies. This would be supported by the mandatory creation of a limited partnership advisory committee in any GP-LP contract involving retail investors. The committee would appoint an independent member designated to represent the interests of retail investors in the fund and keep them informed.

There are few clues as to how such programs could be implemented by authorities. In Asia, some of the most compelling market-level solutions have included the retail-to-PE mechanisms proliferating in Singapore such as iStox and 1exchange. At the very least, these platforms solve for retail investor default risk by requiring entire fund commitments to be made upfront. But they are also effective in illustrating the anonymity and lack of influence of individual LPs making fractionalized contributions.

"If you do it in a stock exchange kind of platform, your investments are going to be very small and liquidity is going to be very low. When you enter, you enter as a very passive investor, and when you exit, you are not sure who is going to be the person buying your stake," says Soo Earn Keoy, who leads Deloitte's Southeast Asia financial advisory practice. "The group of investors is so dispersed, there's no single body that's able to help drive the usage of the money, the monitoring, or helping companies post-investment achieve their goals."

There are a number of growing markets within private equity that may yet prove a round peg can fit nicely in a square hole. For example, secondaries, a niche but steadily growing market, is seen as a good first PE experience for retail investors looking for stable returns rather than homeruns. Early-movers in this space note that while much education is required in terms of familiarizing retail investors with transaction mechanics, the shorter horizons that come with a mid or late-hold investment suit the mass market well.

Meanwhile, impact investing has been mooted as one of the larger potential growth areas for retail PE because deals are generally smaller in size, required return rates are sometimes – but not always – lower, and democratization is fundamentally the name of the game. One of the biggest proponents here is Australia's Impact Investment Group, which defines the opportunity by observing that 55% of the wealth in its home market is owned by individuals who don't meet the hurdles for wholesale or sophisticated investing.

Allocation expansion

One of the key outcomes and drivers of the retail phenomenon in PE will be the expansion of the overall market itself. In a capital sense, this is being fueled by the success of the asset class versus pubic markets and the search for yield amid low interest rates. In terms of the number of stakeholders, it can be attributed to significant degree to increasing demands for information transparency, data analysis, and cybersecurity, which in turn has propelled a growing sub-industry of third-party service providers.

Interestingly, the rise of the third-party players could have a direct impact on the expansion of capital being put to work. Indeed, that is the mission statement of MSCI, a data services provider for fund managers that plans to triple the global asset allocation of institutional investors into private asset classes within 10 years.

This is not as far-fetched as it sounds. Following a tie-up with industry counterpart Burgiss earlier this year, MSCI is said to have access to datasets covering $9 trillion of committed capital in private asset classes, or 90% of the global total. The plan is to provide LP clients with the same level of information symmetry they exploit in the public markets, while allowing GPs to manage increasingly complex and diverse LP bases.

The democratization of private equity down to the level of mass affluent retail investors is not the plan, but it will arguably be a significant side effect. Henry Fernandez, chairman and CEO of MSCI, sees the gulf between public and private markets in terms of investment practices as unsustainable. As these playing fields find common ground, capital flows swell, and the retail wave is realized, private equity investors will have to make some existential decisions.

"The crux of the matter is that over time, the pubic asset classes are going to look a little bit more like the private asset classes. There will be enormous pressure by society to close that gap," Fernandez says. "Participants in private equity, particularly GPs, have a choice: either create a much bigger pond to operate in by making the industry more transparent or stay big players in a small pond. Some will say their investment process is predicated on hoarding information and knowing more than anybody else – but they're going to be niche players."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.