China space tech: Aligning the stars

SpaceX-inspired global fervor about the possibilities of space technology has infiltrated China. Some start-ups appear well set for commercial lift-off, but many others will misfire

Space Angels, a US VC firm focused exclusively on the space industry, estimates that Chinese investment in commercial space assets amounted to $336 million in 2018, or 11% of the global total. In the fourth quarter of 2019, China's share rose to 34%.

It is acknowledged that the country is benefiting from second-mover advantage. The transparency that SpaceX brought by conducting the first private rocket launches and then publishing its budgets has inspired entrepreneurs the world over. Chinese founders have subsequently sent their own rockets into orbit.

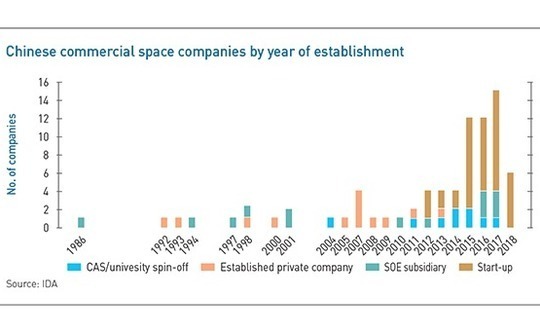

There were 78 domestic commercial space companies as of year-end 2018, according to the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), a US-based non-profit corporation. More than half of these were start-ups formed within the previous three years. Four in five of them emerged from 2015. Of the 78, 21 develop rockets and 29 produce satellites. The rest are involved in areas such as communications, remote sensors, ground stations and downstream analytics.

The risk is that investors get caught up in the excitement. As the IDA points out, most of these companies are not just pre-profit, they "do not even have business plans or a strong sense of who their customers might eventually be." The coming years are likely to see a rationalization of expectations, with capital gravitating to a cluster of sub-sectors that make commercial sense.

As the bedrock of the entire space economy, rocket start-ups should be among the survivors. "A rocket is a seed, a starting point. We are building a road which leads up to a whole new industry," says Roger Zhang, founder and CEO of LandSpace, one of China's top three private launching businesses.

Regulations were issued in 2014 encouraging start-ups to participate in civil-military integration projects. However, progress was stymied by restrictions in areas such as procurement. Wayne Shiong, a partner at China Growth Capital, observes that private companies were not allowed to buy solid fuel engines from state-owned suppliers until 2018. And the ban on foreign capital in the space remains to this day.

Impatient investors

Those who can access the segment see promise in it. Several managers with renminbi-denominated funds have targeted rocket start-ups, reasoning that these companies can leverage state-owned supply chains, government launch sites, a growing base of local talent. This translates into lower costs. Several investors say it costs as little as RMB30 million ($4.3 million) to launch a 200-kilogram payload in China. SpaceX charges $62 million to take a 22,800-kilogram payload into low earth orbit.

Rockets are also regarded as the most commercially viable part of the industry because they are essential. "It's like if you take part in a gold rush, whether you are successful or not, you need a shovel. Rockets are the shovels in the space industry gold rush," says Shang Liu, a senior vice-president at CDH Investments.

Moreover, Chinese GPs are reluctant to wait for the bigger returns that may emerge in other industry segments. Lei Wang, a managing director at CICC Capital, suggests that opportunities in areas such as satellite operation are unlikely to bear fruit within five years.

"Rocket capacity sells out quickly. Limited capacity in this area is a bottleneck for the entire industry," says Shiong of China Growth Capital. Moreover, this commercial potential makes investors more confident about their liquidity options. Listing on Shanghai's Star Market and trade sales to larger strategic players are both mooted as realistic exit options.

The strong preference for rocket over satellite start-ups arguably reflects the immaturity of China's space industry. Globally, satellites and related ground equipment account for 90% of an industry supply chain that is worth $350 billion.

There are three main satellite applications: communication, which typically involves serving users in off-the-grid locations such as airplanes, cruise ships, and mountainous areas; navigation, where China's BeiDou offering is supposed to serve as an alternative to the US-developed Global Positioning System (GPS); and remote sensing, for example providing high-definition images of areas blighted by natural disaster to support the search for survivors.

Feng Yang, founder of Spacety, a Chinese satellite manufacturer backed by Matrix Partners China, Legend Capital and SAIF Partners, tells AVCJ that the most promising application for China is remote sensing. "Communication and navigation both need a constellation of satellites for commercial operation. But for remote sensing, one satellite can work," he explains.

Spacety started out as a satellite assembler before moving into key component fabrication. However, it doesn't sell satellites. The company operates its satellites directly – there are 18 currently in orbit – and teams up with camera manufacturers and other ancillary equipment providers to sell data to customers.

"Our mission is to produce smaller and cheaper satellites for customers that previously couldn't afford to use such services. One of my clients has tens of thousands of acres of land across four provinces in China's northeast. He wants monthly updates on what is growing on his land. If he used his own people and ground equipment to deliver this information, the cost would be enormous," says Yang.

Chang Guang Satellite Technology, which was established in 2014 as China's first satellite company, has followed a similar evolutionary curve. It went from camera maker to satellite assembler to imaging services provider. Some of its revenue comes from specialist agricultural insurers that need information at short order after a natural disaster in order to assess their liability.

Naked ambition

Rival domestic start-ups are more ambitious. Galaxy Space, for example, wants to build the world's leading low-orbit broadband satellite constellation with 5G coverage. It launched its first satellite and is targeting 1,000 in total. The company's latest funding round, which featured Shunwei Capital, IDG Capital and Legend Capital, was at a valuation of RMB5 billion.

However, some investors argue that satellites are not the best channel for delivering 5G. "In China's large cities, the population density is very high and so network base stations are more efficient than satellite solutions," says CDH's Liu. "And then if you offer this service in sparsely populated areas, I don't think there would be enough customers to make it pay."

Other potential applications range from cybersecurity to cloud computing. Chad Anderson, CEO of Space Angels, notes that China has carved out a global leadership position in quantum encryption via satellites – essentially anti-eavesdropping solutions. The country is expected to spend at least $10 billion over the next three years on quantum technology, 13 times more than the US has earmarked for this area.

Meanwhile, UK-based Seraphim Capital advocates employing nanosatellites to offer back-end cloud computing options that ease dependence on expensive ground-based data processing capacity. It is a different, perhaps more informed brand of enthusiasm from that of China's space start-up pioneers, but the risk of running too far ahead of reality is the same.

Zhang of LandSpace may have one eye on the stars, but he is wary of championing ideas when there is no supporting infrastructure. "Whether in China or somewhere else, we are still far from this stage," Zhang says of the cloud computing concept. "When moving storage capacity or computing power from the ground to space, one of its prerequisites is transportation costs are no more than the price of a cabbage."

SIDEBAR: China's rocket men

LandSpace

Founded: 2015

Capital raised: Five rounds, including a RMB300 million ($29 million) extended Series B in 2018 (led by China Growth Capital) and a RMB500 million Series C in 2019 (led by the VC arm of Hong Kong-listed property developer Country Garden)

Profile: The most ambitious of China's leading rocket start-ups, LandSpace has eschewed the small solid-fuel launchers in favor of medium-sized launchers powered by liquid fuel. Last May, it became the first privately owned Chinese company to test a liquid oxygen-methane engine. The product will be rolled out in the third quarter of 2020, with a recyclable model scheduled for launch two years after that.

"As a private player, we have no reason to make solid rockets. It is difficult to guarantee a capacity of more than one metric ton while maintaining economic efficiency. There are already many state-owned players with very mature models for small solid rockets, so we can't really make money there," says Roger Zhang, the company's founder and CEO.

LandSpace claims to have secured contracts totaling more than RMB1 billion, 70% of them from foreign clients. Nanosatellite manufacturers GomSpace, Open Cosmos and D-Orbit, which are based in Denmark, the UK and Italy, respectively, are among its customers.

Wayne Shiong, a partner at China Growth Capital, adds: "By focusing on a liquid-fueled model, LandSpace can control the cost of its own engine. When the recyclable engine is released, profits will increase still further."

OneSpace

Founded: 2015

Capital raised: RMB800 million across four rounds from the likes of CICC Capital, China Merchants Venture, Hongtai Fund and Legend Star

Profile: OneSpace has taken the opposite approach to LandSpace, focusing on solid fuel launchers. It made a successful sub-orbital launch in 2018, the first by a privately owned Chinese company.

Lei Wang, a managing director at CICC Capital, observes that solid and liquid launchers can co-exist in the long term. However, the more mature solid-fuel technology should achieve commercial landings earlier. "The technology is one thing, but the timing to deliver a mature product is another," he says.

OneSpace has also demonstrated an ability to attract traditionally non-space customers. Tian Zhou, an executive director at CICC Capital, notes that the company has expanded into areas such as aviation, equipment manufacturing, and shipping. There are more than 100 customers in total, of which 60 are from outside the space industry.

"The spin-off technology from rockets can be applied to other business areas. OneSpace's engineers are willing to listen to marketing people and use the needs of customers as a starting point to disassemble existing technologies, and carry out further R&D," he says.

I-Space

Founded: 2016

Capital raised: $104 million across three rounds from the likes of CDH Investments and Matrix Partners China

Profile: I-Space, also known as Interstellar Glory Space, works with solid and liquid fuels as well as small and large payloads. Last year, it became the first private player in China to launch a solid-fueled rocket into orbit. This was followed by a test using a 15 metric ton reusable liquid oxygen-methane engine. It plans to test vertical landing this year and a try for an orbital launch in 2021.

"The company is taking small steps but with rapid iteration – this is a good strategy with steady progress," says Shang Liu, a senior vice-president at CDH Investments.

Liu has used I-Space as a steppingstone to other investments in the space industry. These include Istar Space Technology, which fabricates high-quality carbon fiber composite materials used in rockets, satellites and missiles. Other likely applications are cars and high-speed trains. "Launchers have high technology barriers and many technologies can be used in the mass market. This is the logic of our investment," he says.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.