India EV: On a roll

India’s electric vehicle space is nascent but growing rapidly on the back of a concerted policy push. Investors see enormous potential, especially in the world’s largest two-wheeler segment

To understand the extent of China's support for its electric vehicle (EV) industry, one merely needs to contemplate investing billions of dollars in one of the most unstable and conflict-prone countries in Africa. China has recently established a near monopoly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo for cobalt, the nickel-like metal essential to the lithium-ion batteries in EVs. Mega-deals are a perennial feature of bilateral relations, with the value of cobalt changing hands set to reach $50 billion by 2025.

India cannot do this. New Delhi has mimicked Beijing's EV subsidy strategy to some extent, but the sheer economic capacity is simply not there. Nevertheless, sentiment for Indian EV is booming, and private sector capital is expected to follow, both domestically and from overseas. Recent activity includes SoftBank's $250 million investment in Ola Electric, an EV company that spun out from local ride-hailing leader Ola. The business, which is also backed by Tiger Global Management and Matrix Partners India, is now thought to be worth more than $1 billion.

That deal was quickly topped by a $400 million Series C round for Chinese EV maker Xpeng, highlighting not only the difference in investor comfort between the two markets but also a tale of diverging trajectories. While EV in China is set to continue being dominated by private-use cars, India is sizing up bigger opportunities in shared mobility, mobility-as-a-service, micro-mobility, and public transport. These categories are largely urban in nature, benefit from commercially attractive, high-repeat routes, and represent 50-60% of all transportation in the country.

Slow start

Indeed, the fact that India has a less developed private auto market and a behind-trend EV scene is expected to deliver investors some familiar technology leapfrogging advantages.

"Car ownership in India is 22 for every 1,000 people against 150 per 1,000 in China. This means that as the Indian economy grows and more people can afford cars, we will have a situation where the first car for most Indians will be electric," says Jasmeet Khurana, who manages the mobility program at the World Business Council for Sustainable Development in New Delhi. "This, in itself, is a power outcome."

Private equity and venture capital investment in Indian EV has been sufficiently sporadic to defy meaningful statistics. The Ola Electric deal in 2019 is by far the largest in the past 10 years, according to AVCJ Research, with no other PE-backed rounds cracking the $60 million mark. In the past five years, only 17 different EV companies have received any PE or VC backing. The most recent of these was charging systems developer Numocity Technologies, which received a Series A of undisclosed size last week from ABB Technology Ventures, Ideaspring Capital, and Rebright Partners.

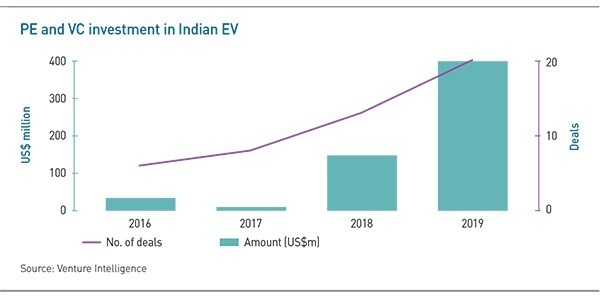

India-dedicated researcher Venture Intelligence offers some of the most bullish figures, tallying 20 deals worth about $397 million in the first nine months of 2019 alone. This compares to $147 million across 13 transactions during the entirety of 2018. Prior years have been decidedly flat, implying the recent lift could be an inflection point, although the low base has kept expectations in check.

A number of factors have underpinned the stagnancy historically. These include high barriers to entry related to the emerging status of the EV space and the massive, fragmented scaling environment of India. Start-ups require a large in-house engineering team or a heavyweight partner to complete the necessary design cycles, as well as at least $50 million to achieve investor-ready milestones in production rollouts. Prototype-level businesses are therefore not getting much attention from the country's software-focused VCs.

Meanwhile, the price-sensitive nature of the Indian consumer market has encouraged a proliferation of cheap products over the higher-quality plays investors prefer. This has aggravated local issues around consumer mindset, including a tendency to associate anything battery-operated with disposable consumer electronics. As a result, big-ticket items like EV have difficulty justifying their price tags, especially relative to traditional internal combustion models. For investors, this is the key marketing hurdle.

India also suffers for a relative narrow range of EVs in terms of form factor. The policy environment to date has done little to incentivize component suppliers, limiting the ability of original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) to maximize supply and set up the servicing networks investors target in other jurisdictions. Battery suppliers are considered less attractive than their Chinese peers, but there is said to be local potential in powertrains, back-end data technology integrations, and retrofitting and end-customer financing services.

The lowest hanging fruit right now is in fleet operation and logistics-related services, but even here, sparse output from OEMs is inhibiting growth. India's existing OEMs, including Tata Motors, Mahindra Electric, and MG Motor, are not confident about demand at current prices and duties for imported vehicles are high. This puts pressure on the supply of different kinds of vehicles to local service providers with operational diversification plans, although signs of a turnaround on the issue are coming to light.

"As new vehicles come in, commercial mobility players like us are able to exploit newer form factors for other segments that we could not otherwise address," says Sanjay Krishnan, founder of Lithium Urban Technologies, a cab fleet operator based in Bengaluru. "For example, early vehicles had an economy of only 120-140 kilometers per charge, so we could never do intercity movement. But now, with both Hyundai and MG vehicles have economies in excess of 300 km per charge, it opens up a new market for us, and viably so."

Charging up

For the moment, transportation appears to be getting more government attention than logistics, which could influence private investment activity in the near term. One of the biggest categories here is city buses, with recent policy support including lowered import duties on the relevant chassis and the standardization of a nationwide public-private partnership agenda to build more vehicles. Tenders are out in four cities, and approximately 5,000 electric buses are expected to hit the road in the next 12 months.

Fleets focused on smaller vehicles could face a tougher de-risking process. Hang-ups in this segment relate to the realities of electrification only becoming economically attractive when vehicles are travelling at least 100-200 km a day – a threshold many car-based businesses in the country do not achieve. As for those that do exceed this amount of usage, they will require all the more servicing support, which does not yet exist.

Lithium Urban has nevertheless demonstrated the potential in this space with recent funding rounds from the likes of the International Finance Corporation and impact investor LGT Lightstone Aspada. The company runs a fleet of about 1,200 cars and has built out its own servicing network of qualified specialist mechanics. Perhaps most importantly, it has also branched into charging infrastructure, with plans underway to install units in seven cities.

A lack of traction in charging infrastructure is commonly cited as a key inhibitor to the expansion of Indian EV. The upfront costs and long timelines to profitability mean that public funding is almost always a must, but little has been done to date due to budget constraints and poor land availability in cities. The government has been widely praised for its current plan tackling the challenge, which will see 5,000 units installed across the country. China, by comparison, already has about 466,000.

US-based Tesla Motors is the only major non-government charging infrastructure provider globally, but the strategy is gaining traction among companies with shallower pockets as a way to cement market share in the early days of the industry. Lithium Urban, for example, is seen as having created a moat for would-be competitors with its charging points, while also accelerating the path to profitability for the sector in general.

"A lot of EV companies say they only provide services, product, or charging infrastructure, and they mostly fail in the pilots," says Vignesh Nandakumar, a partner at LGT Lightstone. "Those that say they'll take responsibility for all three and then amortize the costs have been quite successful. Being in control of your energy source is a huge plus. You don't have to have the IP [intellectual property] on the technology – it could be a partnership – but we see it as a major risk right now if you don't have access or control to your charging stations. And we've also found that it is not too expensive to set them up."

Lithium Urban is LGT Lightstone's only EV investment to date, but the firm has flagged the industry as a key opportunity set going forward and is currently exploring potential investments with a number of related companies. Fleet services is still seen as the best touchpoint for early-stage investors, but the entire value chain is being considered, including components manufacturing.

Policy support

Growing interest has coincided with a substantial policy push that has gained momentum during the past five years. This has been driven by energy security concerns – India imports 80% of its crude oil needs – and an increasingly urgent air pollution dilemma. India is sometimes said to account for more than half of the top-15 smoggiest cities globally.

The centerpiece of the effort has been the FAME initiative, which stands for faster adoption and manufacturing of electric vehicles. FAME has been implemented in two phases, with the first providing subsidies to suppliers, especially OEMs, and the second targeting demand by focusing on incentives for shared and public mobility applications.

In addition to the national agenda, 10 states have published either draft or finalized EV policies, with Tamil Nadu going as far as planning to mobilize up to $7 billion for a dedicated industrial park and VC fund. India appears set to echo the China formula for EV success, however, with little in the way of early-stage start-up investment and most of the action taking place at more advanced stages of development.

"The VC investment phase may never happen in India for EVs, but we'll see real investments in private equity in the next year or two," says Tarun Mehta, co-founder of EV maker Ather Energy. "The government is on the verge of mandating EVs, and for that quantum across the country, you just need massive capacity and distribution creation. How companies will jump over VC remains to be seen."

Ather, which focuses on high-end electric scooters, is itself a counterpoint to this argument, with Tiger Global betting $12 million on the company when it was still in the prototype phase. After Ather got its EVs on the road, local motorcycle manufacturer Hero MotoCorp led a $51 million round, with InnoVen Capital India providing $8 million in debt. "Once companies are over that hump, the sector is going to attract growth capital in a very significant way," Mehta says.

In the long run, Ather appears likely to remain an exceptional case. Ashish Sharma, CEO at InnoVen, notes that India doesn't have many success stories when it comes to building world-class products, and relatively few companies are trying to build cutting edge products. Ather, for its part, claims to be the only electric two-wheeler company with its own charging infrastructure. It has set up about 50 units to date and plans to install another 100-200 in the next few months.

"We saw what was out there and felt that Ather was among the more evolved players, when it came to R&D, IP and focus on customer experience," Sharma says. "Our thesis is that there'll be a pervasive shift from internal combustion engines to EVs and while there are infrastructure and cost issues, I wouldn't be surprised if the whole shift to EV in India happens over the next 10 years."

Most of this traction is going to happen in the two-wheelers and three-wheelers, an unorganized market of last-mile logistics and transportation businesses that has become the most quickly electrifying vehicle segment despite a dearth of subsidies. Much of this progress is attributed to their ease of conversion. The vehicles are basic, with few electronic engineering issues. Perhaps most importantly, unlike cars, they can be plugged into normal power outlets.

There are no reliable figures for this space, but the number of electrified vehicles is easily in the millions, mostly in tier-two and tier-three cities. The vast majority of these are acid-led battery models, which is the easiest, most cost effective option for the price-sensitive segment. A transition to lithium-ion has been put into motion through a targeted subsidy scheme under FAME rules.

At the same time, two-wheelers and auto-rickshaws are proving to be the cradle of local battery innovation, especially in battery swapping. Numocity is a specialist in this field, and Uber recently partnered with local technology developer Sun Mobility in a battery swap infrastructure program. Gogoro, a PE-backed electric scooter maker based in Taiwan, is also helping to advance the technology locally. Battery swapping has attracted interest from last-mile players because it effectively removes the most expensive component of fleet vehicles from the initial purchase price.

All of this is expected to help India's EV space circumvent the challenges around charging infrastructure plaguing countries with transportation sectors more focused on full-sized cars. India overtook China to become the biggest two-wheeler market in the world in 2016 with 22.4 million units sold, including commercial three-wheelers. This peak has eroded in the meantime, but the market still claims top spot globally.

"Two-wheelers and three-wheelers are the largest opportunities for electrification in India, and investors need to start looking at start-ups there because that's a space where they can scale in the long run," says Aswin Kumar, an associate director at Frost & Sullivan. "We're talking 20 million two-wheelers a year, so even if you have only 10% market share, that's two million units. It's a risk that investors need to take, even in the very early stages."

Full Blume?

Blume Ventures is one of the firms taking those bets. Its investments include Routematic, a software developer building tools for an EV-centric smart city network, Yulu Motors, an e-bike sharing company, and Euler Motors, a manufacturer of fully electric three-wheelers. The firm has also explored battery, motor, and charger suppliers, as well as researchers doing new battery chemistry.

Part of the Blume approach, particularly with Euler, has been to make sure products are physically stress-tested with India in mind. This includes wariness around tropical climatic conditions, varying landscapes, and a cultural tendency to overload vehicles.

"You could design a vehicle which is 80% efficient in converting electrical energy into kinetic energy, but converting 95% of that on an engine in an Indian on-road scenario is something that is going to be critical for a vehicle to win in this market," says Arpit Agarwal, a principal at Blume.

Euler has built about 200 EVs and claims to have the largest charging infrastructure portfolio in the Delhi area with some 200 captive stations. These are expected to become public charging points in the future when overall demand increases. The company also manufactures its own batteries and has set up logistics partnerships with online grocer BigBasket and delivery services player Ecom Express.

"My advice is very simple – the opportunity for EVs is already large and is going to become much larger from now," says Agarwal. "There is absolutely no reason for a VC to not consider looking at a bunch of companies and hopefully invest in some of them, because this is going to become a very important part of our lives in a few years' time."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.