China PE: Tipping point?

Uncertainty continued to weigh on China private equity deal flow last year, leaving plenty of capital sitting on the sidelines waiting to reengage. GPs see diversification as an antidote to competition

"We continue to seek out Chinese buyers in our exit processes. We still have the concept of the Chinese buyer wildcard with the bid that comes in at many multiples higher than anyone else – you say a silent prayer for that," Nick Bloy, a managing partner at Navis Capital Partners, told the AVCJ Forum in November. "But the phenomenon has basically disappeared."

In Southeast Asia, Navis' primary theater of activity, Chinese strategic interest remains vibrant in the tech space as investors pursue innovation-driven trends that have played out in the domestic market. But M&A activity involving Chinese buyers in the region has dropped off, coming in at $3.5 billion in 2019, according to AVCJ Research. It is the lowest level in four years and a fraction of the $15.9 billion record high set in 2017, which now seems like a glorious outlier.

The decline is inextricably linked to a government crackdown on outbound investment in late 2017 amid concerns about capital flight and wanton spending by Chinese conglomerates. Since then, the country has endured slower growth, uncertainty fueled by tensions with the US, and a liquidity crunch.

Corporate enthusiasm for M&A has not only dampened, but some companies are actively trying to sell assets. CITIC Capital's two most recent corporate carve-outs came from Chinese sellers: China Merchants Group offloaded packaging business Loscam, and Qingdao KingKing Applied Chemistry divested digital marketing player Hangzhou UCO Cosmetics.

"Those wildcard bids have dried up, and taking it one step further, many of the deals they did three or four years ago are starting to unwind," says Boon Chew, a managing partner at CITIC. "If you have dry powder, if you have relationships on the China side, if you know what you are looking for and can move quickly, there are assets that can be bought for reasonable valuations. And they didn't just buy Chinese assets, they bought regional and global assets."

The emergence of motivated domestic sellers adds a fresh twist to a private equity market that for the best part of two years has served up a rich mix of threats and opportunities. Will 2020 be remembered for a breakthrough in buyouts and a return to form for growth capital or just more of the same? Private equity firms must prepare to adapt even if it means a long wait for the payback.

The waiting game

Twelve months ago, there was cautious optimism among Chinese GPs that 2019 would be more productive than 2018 as the volatility that previously held them back turned into opportunity. Entrepreneurs were becoming more reasonable on valuations and more willing to work with third-party investors as they sought responses to a difficult operating environment.

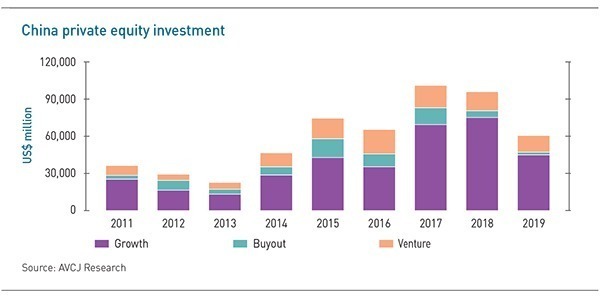

Investment data suggest this has not played out. Around $60 billion was deployed in China last year, down from $95 billion in 2018. Buyouts remain somewhat negligible – a large take-private has a distorting effect on the headline number – so the standout statistic is growth capital, which fell 40% to $44.6 billion. There are two caveats. First, there is less local competition due to a weak renminbi fundraising environment. Second, late-stage rounds for technology companies dominated growth activity in 2018, accounting for two-thirds of all capital committed. In 2019, this share fell to 45%.

"The WeWork situation has caused everyone to think about what they are paying for. A company might have a great business model but if it still hasn't registered profitability, this is going give people pause when paying high valuations," observes Teck Sien Lau, CEO of Hopu Investments.

However, his bearish view of the market stretches beyond technology. Hopu anticipates an L-shaped scenario – not a full global financial crisis – with minimal asset price inflation and multiple expansion. Volatility and policy risks abound in China, which means investors are being very careful in their approach. On top of that, private markets are currently more expensive than public markets, Lau notes.

"People are underwriting a lot more cautiously today than they were 18 months ago, but at the same time, there is so much money chasing deals in China it still feels like a seller's market," adds CITIC's Chew.

There is dry powder aplenty in private markets globally. One reason for pent-up interest in China is the trade-off between short-term macro concerns and long-term growth expectations. Most PE investment strategies have more to do with fundamental shifts in consumption behavior once GDP per capita crosses the $10,000 threshold than periodic slowdowns in shopper sentiment. They should, in theory, be able to wait out cycles.

For GPs looking to deploy capital in a climate of ample liquidity, there is only one sustainable response: cultivate differentiated deal flow. It is still possible to grind out proprietary transactions in China by leveraging relationships, but a growing number of local PE firms are focusing on specific themes where they have some degree of domain expertise. With this comes access to people, information and assets that are beyond the reach of others, which in turn generates unique deal flow or enables them to underwrite more aggressively in competitive situations.

The logical longer-term evolution is the advent of true sector specialization. Most private equity firms are still generalist, although their interpretation of this has narrowed from outright opportunism to concentrating on a handful of relatively broad areas. There is a general expectation that China will come to look more like the US, with GPs that concentrate on distinct sectors and transaction types. The question is how quickly it might happen.

This mindset is already discernable in the language of global private equity firms operating in the market. "We try to figure what key themes are relevant and we identify categories or sectors that make sense within those themes and have tailwinds and longevity. Then we look to position ourselves around assets we find interesting within those sectors and themes," says Edward Huang, The Blackstone Group's head of private equity for Greater China and Korea.

Having a global platform is helpful in terms of pattern recognition and resource sharing. Blackstone, like most of its peers, has sector teams that operate across all geographies – supporting investment professionals on the ground – and relationships with former senior executives from a wide array of companies who can serve as advisors during due diligence and as board members post-transaction.

Permira takes a similar approach built upon five core sectors: technology, consumer, financial services, healthcare, and business services. According to Kurt Björklund, the firm's co-managing partner, 15 years ago success in Europe was largely predicated on geographic access. Now domain expertise wins deals. In Asia, a compromise solution is required, where market access is combined with some level of pattern recognition based on Permira's knowledge of the evolution of sectors globally and its assessment as to how this can be applied locally.

"We want to be a great counterpart to leadership teams that are building businesses along themes we have backed many times before. Our culture is such that we deliver on that in an integrated way," he says. "As the Asian market develops, we will see more and more of that need for specialization, but it's a 10-year process."

Favored themes

Some Chinese GPs are already progressing along the evolutionary curve. FountainVest Partners, which is among the larger local players with more than $4 billion under management and three US dollar-denominated funds, traditionally organized its portfolio management operations based on functional expertise. In the last few years it has started recruiting expert advisors who provide insights into certain sectors.

This has run in parallel with efforts to cultivate ecosystems within industries. In 2016, FountainVest established a joint venture fund with Focus Media, a Chinese outdoor advertising business it privatized in the US and then re-listed in China, that focused on sport-related assets. Later the same year, it agreed a similar partnership with WME-IMG, a sports and entertainment talent management agency now known as Endeavor, working alongside Sequoia Capital China and Tencent Holdings.

Several direct sports investments have since followed. In 2017, FountainVest teamed up with one of its LPs, Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan (OTPP), to buy Hong Kong-headquartered fitness center and yoga studio operator The Pure Group. The goal is to expand the business into mainland China. Last year, the GP was part of a consortium that paid EUR4.6 billion ($5.2 billion) for Amer Sports, the Finland-listed owner of brands such as Salomon, Atomic and Louisville Slugger.

"Consumer is such a huge industry, even though everyone says they are focusing on it, they have different focuses as well," says Frank Tang, chairman and CEO of FountainVest. "We haven't got time to focus on education yet, but we spend a lot of time on sports and fitness."

This applies as much to healthcare, where investments range from hospital operators to medical device manufacturers, as it does to consumer, where FountainVest focuses on sports and fitness and Centurium Capital is well versed in food and beverage. Michael Chen, a partner at Centurium, observes that he is happy to cede the former to FountainVest in order to take advantage of vertical opportunities that arise in the latter from exposure to businesses like Luckin Coffee.

Private equity firms must therefore resist the temptation to spread themselves too thinly in target sectors because it dilutes the impact of knowledge and networks developed through repeat use. "We look at every sector and the potential high-growth areas in each one, and then we allocate resources to areas we want to focus on," says Chen. "But I think it takes a long time to get that ecosystem built up. We really have to spend time in those places we focus on."

It is arguably easier for the small subset of GPs that already have a sector focus – even if for the time being concentration essentially constrains fund size. Maison Capital's consumer strategy is based on a comprehensive, longstanding research program that maps out the competitive landscape. For example, it underpinned an analysis of the convenience store space that ultimately led the firm to start making investments in community grocery stores.

Lunar, meanwhile, builds businesses around themes within the consumer sector, such as children's clothing and snack foods. The aim is to operate – and be perceived – as an industry insider rather than a PE investor, using the knowledge and networks gained through one acquisition to source complementary assets on a proprietary basis. It has even set up standalone companies specializing in digital marketing and e-commerce to service the entire portfolio.

Buyout imperative

The firm's approach chimes in with an observation from Blackstone's Huang that "as you spend time in these sectors, you gain not only expertise but also access to other opportunities within sectors." And if this sounds like a classic developed market roll-up strategy whereby platforms are created to consolidate fragmented industries that's because it meets those criteria.

The move toward specialization within China's GP community is not inextricably linked to the rise of buyouts, but the two phenomena share a lot of common ground. Domain expertise is increasingly important when pursuing deals of any kind: competition has placed a premium on differentiation; entrepreneurs are more familiar with private equity; and companies need to find answers to questions they've never had to answer before. But with buyouts it is an essential part of value creation, serving to draw investors back to areas they know well.

Perhaps the market is too nascent for individual firms to have plowed their own furrows, though some might claim considerable experience in privatizing US-listed Chinese companies and carving out China assets from multinationals. The missing piece is succession, which has no sectoral affiliations. While many entrepreneurs retain their youth and motivation, if the harsh realities of running a business in a slower growth environment don't catch up with them, age certainly will.

"The generational succession issue is the tip of the iceberg. When that comes, there will be a huge wave," says FountainVest's Tang. "Most entrepreneurs of this age tend to have just one child."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.