2019 in review: Falling short

Fundraising, investment and exits in Asia are unlikely to match last year as pan-regional funds take a back seat, large-cap buyouts remain in short supply, growth-stage tech loses its edge, and IPOs flounder

Country funds: Time to shine

China managers steal the spotlight as pan-Asian players step back, albeit temporarily

Pan-regional funds sucking up the bulk of the capital allocated to Asia has become a feature of the industry in recent years. Not in 2019. With December nearing the mid-point, there has been only one final close above $2 billion for a pan-regional strategy, down from seven in 2018. TPG Capital closed its sixth Asian vehicle at $4.6 billion in February. Admittedly, Warburg Pincus went on to collect $4.25 billion for its latest regional companion fund, but it is essentially China-focused with a small allocation to Southeast Asia.

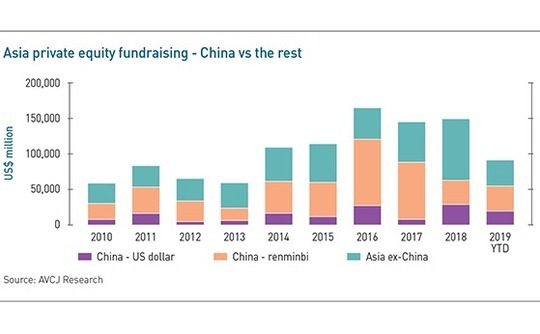

As a result, overall fundraising is comparatively weak. A total of $90.8 billion has been committed to Asian managers so far, down from $148.4 billion last year. Strip out the renminbi-denominated funds and the total has slipped from $114.7 billion in 2018 to $55.9 billion in 2019. It is on course to be the lowest annual total since 2013. Meanwhile, the pan-regional share of fundraising activity has dropped sharply. It is currently 29%, having reached 42% in 2017 and 50% the following year.

None of this should be overly concerning. The headline fundraising number is a function of whatever big beasts happen to be in the market and only five pan-regional managers have succeeded in crossing the $6 billion threshold. That should become seven in 2020, with MBK Partners having set a $6.5 billion hard cap for its sixth fund and Baring Private Equity Asia expected to collect around the same amount for its seventh. Moreover, KKR Asian Fund IV has launched with a target of $12.5 billion.However, the retreat of pan-regional players has shone the spotlight on country managers once again, albeit temporarily. As recently as 2017, US dollar China funds accounted for a paltry 12% of Asia fundraising. That share has risen to 35% as of mid-December 2019.

No major market in Asia has seen an uptick in fundraising activity in 2019. But China does illustrate the stark contrast in fortunes between the haves and have nots. In the past three years, China executives from KKR, Warburg Pincus, MBK Partners and The Carlyle Group have spun-out to form DCP Capital, Centurium Capital, Nexus Point Capital, and Rivendell Partners, respectively. They want to leverage their size, nimbleness and networks to secure deals that were beyond the reach of the global firms.

Between April and June, three of them achieved final closes. DCP and Centurium both completed sizeable and rapid fundraises, each closing on $2 billion (with DCP collecting a further $500 million for a renminbi-denominated sidecar). Nexus Point and Rivendell, both of which target smaller pools of capital for mid-market buyout strategies, found it harder. Nexus Point closed below target at $475 million, while Rivendell is defunct, with founder Alex Ying moving to CDIB Capital.

China-focused funds account for six of the 10 largest final closes in Asia. Warburg Pincus ($4.25 billion and an asterisk because it also does Southeast Asia), Boyu Capital ($3.6 billion), Primavera Capital Group ($3.4 billion), and CITIC Capital Partners ($2.8 billion) sit alongside DCP and Centurium. These are some of the largest US dollar China funds ever raised by independent managers. Exclude Warburg Pincus and these managers still absorbed nearly three-quarters of all capital that went to China funds.

It is worth noting that only CITIC Capital could be considered a country manager of long standing. Boyu and Primavera are each less than a decade old, while DCP and Centurium are less than half that age. They are the desirable younger generation of Chinese private equity – perceived as being in touch with technology trendsetters as well as policymakers.

Hahn & Company might claim to fulfill the same role in South Korea. Founded in 2010 by Scott Hahn, formerly CIO of Morgan Stanley Private Equity Asia, the firm closed its third fund this year with $2.7 billion in core equity and a $500 million co-investment vehicle for larger transactions. Hahn raised $750 million for its debut vehicle as recently as 2011. Now it manages comfortably the largest fund ever raised by an independent GP for deployment solely in Korea.

With corporates reluctant to sell or buy assets amid global uncertainty, big buyouts are left in limbo

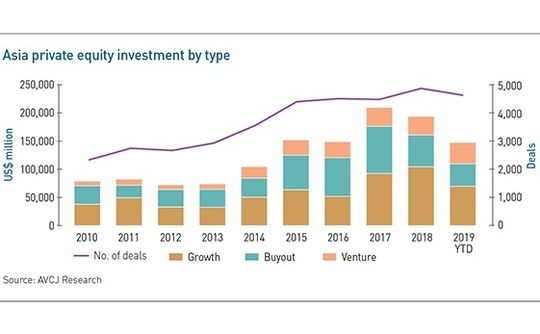

It has not been a good year for mega deals, whether private equity is buying or selling. Investment in Asia reached $192.4 billion in 2018, about $15 billion short of the record set the previous year. For 2019 to date, the total is $146.5 billion, substantial by historical standards but hardly indicative of a multi-year paradigm shift that justifies ever increasing fund sizes.

The drop-off in growth equity activity is understandable: participating in late-stage rounds for potentially overvalued technology unicorns has fallen out of favor with many investors. Buyouts are the other area of weakness, which represents the continuation of a trend that emerged last year. In 2017, there were 16 buyouts of $1 billion or more and they accounted for about one-quarter of aggregate deal value in Asia. There have been 12 in each of 2018 and 2019; their contributions to overall investment in the region are 12% and 13%, respectively.

Exits are in a similar position. They stand at $59.2 billion for 2019, down from $122.5 billion in 2018. Public market activity has been weak, with IPOs and open market sales down, but trade sales are what moves the needle in Asia. Exits to strategic investors have slipped from a record $100.1 billion in 2018 to a distinctly average $54.6 billion. In 2018, there were 27 trade sales of $1 billion or more, including five in excess of $3 billion. There have only been 15 so far this year, of which two surpassed $3 billion.

Perhaps only the Korea thesis is borne out by the numbers in 2019. Buyout activity has increased for four consecutive years, with Lotte Corporation and LG Corporation among those recently divesting assets. (Admittedly, the two largest Korean deals this year are both secondary buyouts). More capital was put to work in Japan buyouts as well, but it is difficult to reconcile this with the expectations of a proliferation in large-cap investment opportunities. Two deals squeezed into the $1 billion-plus category, compared to zero in 2018 and four in 2017.

The overriding dynamic might be valuation anxiety. Corporates are reluctant to buy or sell into a down market and there is plenty to worry about in terms of global macroeconomics and geopolitics. In this respect, a drop in private equity transactions involving corporates is consistent with a broader slowdown in M&A.

From the perspective of private equity pursuing large buyouts, another key theme is the need for conviction when competing for assets at high valuations. Through industry insight, operational expertise, cross-border synergies, or platform structures, they must find a way to squeeze more value out of an asset. A byproduct of this is a preference for stable, high growth industries and – in some cases – the utilization of capital pools that require lower returns.

There is evidence of this approach among the top buyout deals of 2019. Brookfield Asset Management, for example, is responsible for the two largest transactions. Both targets, Vodafone New Zealand and Australian hospital operator Healthscope, could be placed at the nexus of private equity and infrastructure, albeit at different points. Much the same could be said of Daesung Industrial Gases in Korea, which Macquarie Infrastructure & Real Assets bought from MBK Partners, and TPG Capital's acquisition of Columbia Pacific Management's Southeast Asia hospital business in conjunction with a Malaysian strategic investor.

KKR took it a step further with the purchase of a portfolio of Asian assets – the most significant of which is Australian biscuit brand Arnott's – from US-listed food multinational Campbell Soup. The GP opted to participate through its core investments strategy, a balance sheet vehicle for assets that are stable, cash-generative, but aren't a good fit for private equity funds because the holding periods are deemed too long and the expected returns are deemed too low.

A drop-off in late-stage tech deals suggests China's unicorns are no longer coveted creatures

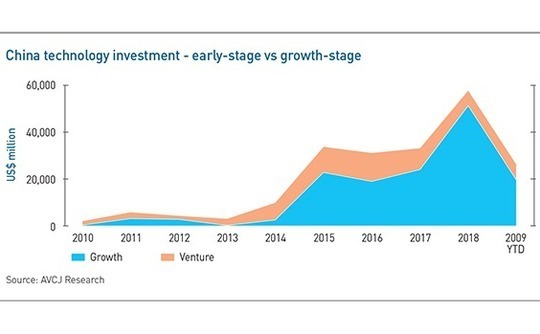

In retrospect, the turning point for China technology investment came in 2014. Alibaba Group and JD.com both listed in the US, underlining the scale achieved by e-commerce. Online-to-offline services and ride-hailing were on a similar trajectory, raising ever-larger private funding rounds at ever-higher valuations. Venture capital fundraising more than doubled on the previous year, surpassing $11 billion.

Over the ensuing years, VC fundraising and investment have peaked – both in 2016 – and gradually fallen back. Commitments to funds stand at $6.2 billion for 2019, down from $20.9 billion the previous year. On the investment side, $5.5 billion in 2014 became $11.3 billion in 2014 and ultimately $19.6 billion in 2016. For the current year, it is $12.8 billion.

More startling, however, is the rise and fall of growth capital participation in mid to late-stage technology deals. A total of $22.7 billion was deployed in 2015, a tenfold increase on the previous year, and by 2018 it reached $50.9 billion. A paltry $19.4 billion has been deployed so far this year. Region-wide, venture capital investment is up on 2018, supported by activity in India and Southeast Asia. But growth-stage technology transactions are down by more than 50% at $27.5 billion. Their share of overall private equity activity in Asia has fallen from one third to less than one fifth.

It is unfair and inaccurate to describe this as the WeWork effect. Questions about the sustainability of consumer-facing internet businesses that burn through cash in the battle for market share are nothing new. But technology fell victim to a broader malaise at the end of 2018 as public markets plunged. This led to a crisis of confidence in valuations that ran deep into 2019. Investors were uncomfortable going into pre-IPO rounds for unicorns when there was no certainty as to when a liquidity event would happen, and if it did, whether the public markets would endorse heady private market valuations.

In 2018, there were 24 funding rounds for Chinese technology companies in the $200-499 million range, seven of $500-999 million, and 11 of $1 billion and above. In 2019, those numbers have fallen to 13, six, and four, respectively.

China-based businesses have attracted four of the 10 largest private equity investments in Asia since the start of the year, including three of the top four. They are all growth equity transactions, but they don't necessarily fit the consumer internet profile.

Hillhouse Capital leads the rankings, having paid $5.6 billion for a 15% stake in Gree Electric Appliances, a technology company only in the sense that it manufacturers air conditioning units. It is followed by a $3.7 billion investment in Tenglong Holding Group, a data center operator. Short video platform Kuaishou – which received $3 billion from an investor group featuring Boyu Capital, Sequoia Capital China, Yunfeng Capital, Temasek Holdings and Tencent Holdings – is consumer-facing but it's one of few.

There are 13 Chinese companies featured among the 50 largest deals from 2019. Barely half of these could be labeled technology-driven growth capital, and a couple primarily serve enterprise customers. Last year, China accounted for 21 of the top 50 and about a dozen were consumer internet, including five of the 10 largest across the region.

Jittery public markets investors give a lukewarm response to private equity-backed offerings

It has been three years since a company with a private equity investor raised more than $100 million in an Australian IPO. Public listings are a challenge for anyone in the country right now, but the poor showing from financial sponsors – especially given historical evidence that suggests they outperform the rest – is a sad indictment of how retail investors have fallen out of love with PE-backed offerings.

Two companies from opposite ends of the corporate development spectrum sought to buck the trend in 2019: Latitude Financial, a consumer lending business that GE Capital sold to a private equity consortium for A$8.2 billion ($5.5 billion) in 2015, filed for a A$1.4 billion IPO, while PropertyGuru, a 12-year-old online property start-up from Southeast Asia, announced plans to raise A$380.2 million. Both offerings were pulled with concerns about after-market performance a common issue.

There have been four private equity-backed IPOs in Australia so far this year, most of them small-scale consumer internet businesses, with aggregate proceeds of $122 million. The window for larger offerings was last open in 2013-2015 when 48 companies raised a combined $12.6 billion.

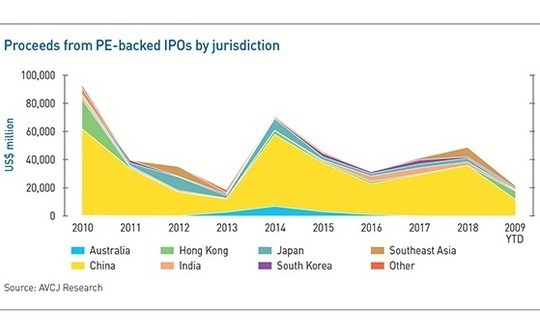

The story was similar for Asia as a whole. Proceeds from private equity-backed IPOs have fallen from $48.5 billion in 2018 to $21.2 billion in 2019, a six-year low. The number of offerings stands at 120, down from 188 in 2018. Incredibly, one must go all the way back to 2001 to find weaker annual volume. Investors were equally wary about selling shares in companies that are already listed. Open market sales have fallen from $8.6 billion in 2018 to $1.75 billion this year, the lowest since 2008.

The numbers are weak across all major markets, even though their stock market indices in the likes of Japan, India and Australia have overcome the first-quarter jitters and are now in positive territory for the year. The picture remains more volatile in Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Indeed, 37 PE-backed offerings have raised $4.6 billion on the mainland bourses this year, compared to $12.3 billion from 49 IPOs last year. Activity has been slowed by closer scrutiny of IPO candidates, but this year also saw the launch of the technology innovation board, which is supposed to facilitate listings by start-ups through streamlined approvals, approval for weighted voting rights, and an acceptance of pre-profit businesses. According to AVCJ Research, 13 PE or VC-backed companies have raised $1.9 billion via what is now known as the Star Market. Without them, things would look much bleaker.

Listings by Chinese companies with financial sponsors in the US are also down on 2018, while most of those that have made it to the New York Stock Exchange or NASDAQ ended up raising less than planned. Ten companies had raised $2.3 billion as of mid-December. Last year, 22 attracted $8 billion.

Hong Kong remains something of an outlier, though 2019 has hardly been easy. The exchange played host to six of the 10 largest private equity-backed IPOs in the region and 20 overall, with proceeds reaching $10.4 billion. In 2018, 23 companies raised $15.4 billion. Even so, there is still a trend of large offerings failing to gain traction in Hong Kong. Notably, Budweiser Brewing – which qualifies as a private equity portfolio company only because of GIC Private's pre-IPO investment – raised $5.8 billion, but the total is about half what the company sought to raise before aborting the process three months earlier.

This is not the only case of IPO disruption. Pan-Asian logistics player ESR postponed its offering in June, shortly after protests in Hong Kong – which were triggered by now-withdrawn extradition legislation but have grown to encompass a variety of grievances – grew in scale.

Concerns about instability spooked the entire market and the Hang Seng Index remains volatile. However, ESR returned in November with a larger listing and went on to raise $1.6 billion, enabling early backer Warburg Pincus to take $830 million off the table, the largest exit via IPO of the year. Alibaba Group is no longer a private equity portfolio company in the traditional sense, but its return to the Hong Kong bourse through a $12.9 billion offering – taking advantage of a weighted voting rights structure not available to it in 2014 – made for a bold statement.

India and Southeast Asia become the preferred destinations for investors with the US off limits

Of the $224 million raised to date by Indian social networking and content-sharing platform ShareChat, more than half has come from Chinese investors. The start-up's $100 million Series D round, which closed in August, was led by Twitter but it also featured TrustBridge Partners as a new investor. The private equity firm became the latest Chinese addition to a roster that includes Shunwei Capital, Morningside Venture Capital, and mobile phone brand Xiaomi.

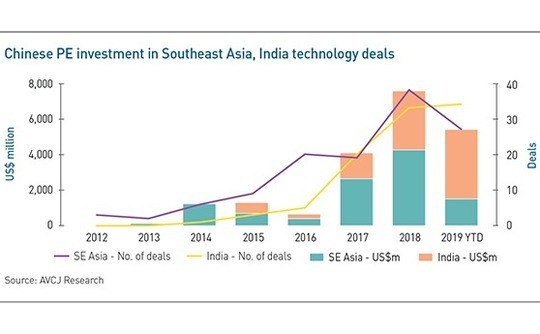

Shunwei, which was established by Lei Jun, the co-founder of Xiaomi, made its debut India investment in early 2017, backing used car trading platform Truebil. It has since participated in funding rounds for at least eight other Indian start-ups – ShareChat among them – and entered Southeast Asia, building up a nascent portfolio that includes Indonesian ride-hailing and delivery giant Go-Jek.

Shunwei is not the only Chinese VC firm entering these geographies. GGV Capital has five portfolio companies in Southeast Asia and two in India, Morningside has four in India and one in Southeast Asia, while Qiming Venture Partners has one in India and two in Southeast Asia. These are just four of the most prominent China investors with funds at or near the $1 billion mark. Various other GPs have been established solely to pursue China cross-border strategies, with Southeast Asia often a prime target.

According to AVCJ Research's records, Chinese venture capital investors have participated in nearly 30 funding rounds for Indian technology start-ups this year. There were no deals until 2014 and then only a handful each year before interest took off in 2017. Last year, the total was 33. Southeast Asia got traction slightly earlier. Chinese VCs backed 20 start-ups in 2016, having first entered the market in 2011. Last year, they took part in 35 rounds and there have been 24 in 2019 to date.

These investors – and the Chinese strategic players they often accompany, such as Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings – can write big checks. In 2016, there were three funding rounds of $200 million or more in India. There have been 14 so far this year. Southeast Asia has grown from one $200 million-plus deal in 2015 to six in 2019.

Regulatory obstacles in the US – the previous go-to overseas market – appear to have encouraged investors to double down on emerging markets within Asia. However, there are also strong strategic reasons for targeting India and Southeast Asia. Internet-enabled business models will not evolve in these jurisdictions in the same way as China, but there are similarities.

For investors looking to diversify their exposure at a time when numerous segments of China's technology space are either overvalued or oversaturated, there are worse – or at least more challenging – places to try and find new pockets of growth. Africa, for example.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.