Consumer hardware: Some assembly required

Consumer hardware is a cratered landscape in venture capital, and the risk-reward equation is not particularly well understood. New ways of looking at a traditional industry are needed

Laundroid, a refrigerator-sized black box that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to fold laundry, was the toast of Japan's robot scene last year when it secured $92 million in venture capital funding from a group of local tech conglomerates and KKR founders Henry Kravis and George Roberts. As early as the Series C round in 2017, expectations were swirling that annual revenue could hit $2 billion. Last April, the start-up filed for bankruptcy.

To some extent, the episode has been chalked up to the fact that a stamp of approval from high net worth individuals – even investment luminaries the likes of Kravis and Roberts – remains a far cry from a proper financial endorsement. The nature of Japan's start-up environment has also taken some of the blame. This market is seen as a risky cocktail of novelty hardware fascination and strong dependence on corporate investors that have myriad non-financial motivations and a tendency to treat early-stage investees more like sluggish suppliers than promising seedlings.

The most incisive observations, however, come back to the realities of building a business in consumer hardware. Laundroid was often criticized for lacking functional versatility and failing to prove demand, but its problems may have been more technical than product-market fit. Using robotics to handle soft materials like clothes is harder than sorting other fragile items such as eggs. The AI component attracted capital, but computer vision was the easy part. This is a recurring issue in autonomous cars as well: new sensory AI sparks excitement until previously dismissed mechanical hurdles finally stymie the rollout.

Time to tinker

There is an encouraging story here in the ability of an offbeat start-up to attract capital for an unproven device, since it demonstrates a willingness to back teams with ambition and ideas. However, it also reveals the pitfalls of taking this path without knowing the hardware ropes. Conventional wisdom states that once a company commits to physical production, it has passed a sink-or-swim point of no return. But there is indeed time for tinkering – it just has to be built into the plan. For investors, the key to consumer hardware may be in an understanding that, unlike software, fast scaling is not the game.

"Consumer tech is actually great when you've got devices in the hands of customers because you've got this really nice economic relationship with them if they're paying a subscription fee on top of a piece of hardware. What's challenging is the lead time for ordering those components and having that locked up in a supply chain before it gets to the customer," says Duncan Turner, a managing director at hardware accelerator HAX. "It means there is a capital-intensive period right at the start of the business while its scaling before it's really proven."

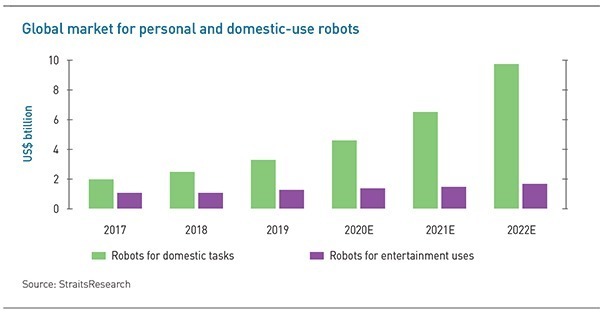

Shenzhen-based HAX focuses exclusively on hardware but the vast majority of its investments sell a service enabled by a physical product rather than the product itself. Its portfolio has shifted from 80% consumer and 20% enterprise in 2012 to 90% enterprise today. This is a common transition among hardware specialists, even as the bulk of the broader VC universe extols consumerism as its raison d'etre and the opportunity set for consumer hardware expands. The currently $4.6 billion global market for personal and domestic-use robots will grow 26% to 2026, according to StraitsResearch.

Tales of Laundroid-style wreckage are part of this counterintuitive story of consumer hardware denial, but they are by no means the driving factor. With the advent of the internet and the expansion of e-commerce, it became clear that asset-light B2C models had an advantage. But as the online economy has matured, competition has intensified and the social media advertising driving much of the growth has become more expensive. As a result, the commonsense view that asset-light software is more economically playable than hardware has become harder to reconcile in raw numbers.

The turnaround in this thinking started in the US with the IPO of Fitbit. The wearables maker was valued at $6 billion on listing in 2015, representing a 90x paper gain on total investment since only $66 million of VC had been pumped in. There have been similar stirrings in Asia, with Chinese smart phone maker Xiaomi going public last year at a $54 billion valuation after receiving $3.4 billion in VC backing. By comparison, Chinese ride-hailing leader Didi Chuxing has received $21.2 billion in VC funding to date and sports a $55 billion valuation, suggesting a lower capital efficiency.

US, France, and Japan-based VC investor Hardware Club was founded in 2015 as industry consciousness of this theme began to sink in. It closed its debut fund at $50 million last year and has split investments evenly between the US and Europe, with Asia remaining of interest but so far seen as lacking in sufficiently viable companies. Still, Jerry Yang, a general partner at the firm, points to activity such as the $500 million Hong Kong IPO of gaming equipment maker Razer in 2017 as a sign that hardware's deceptively sound economic fundamentals are increasingly being recognized in the region.

"Pure software start-ups are not more capital efficient than hardware ones – it's a misunderstanding," says Yang. "Some of the most capital efficient and most profitable deals in the past decade are actually hardware companies. If you look at the money that software start-ups spend, you can use it to launch very good hardware companies very easily. The main difference between hardware and software is that software companies seem to get more results than hardware in the early stages for the same amount of capital, but you just have to crunch the numbers. You cannot just base things on perception."

Dual speed

This view says much about the need for investors to consider business building at a different speed in hardware. Software companies will get quick results in user traffic and other intangible metrics, which are often driven by free offers and difficult to tie to real incoming cash flow. The longer road of hardware by comparison can ultimately reap greater rewards, especially in consumer categories, but there must be sensibility around the core pros and cons.

Some of the advantages of consumer hardware include higher rates of customer loyalty. Essentially, people tend to stick with a device longer than an app, although the benefit can only be leveraged when the business model has exposure to the service or subscription component. This effect is magnified in consumer versus enterprise hardware because individual customers are generally more forgiving when new products are still ironing out software bugs. Few other business models, online or off, can accommodate false starts of this kind.

What defines the homeruns from the also-rans in consumer hardware is not dramatically different from those in enterprise hardware or even software, except in nailing down the target market. This is a more painstaking yet less precise process at the consumer level, to some extent de-risked by the use of crowdfunding to gauge public appetite but still reliant on surveys, focus groups, user testing, and simply monitoring the traction of similar products.

"One of the absolute worst things they can do is the whole ‘build-it-and-they-will-come' policy. There is absolutely no sense in building a product until you can prove there is demand, or until you can prove that you've got some early traction," says Bryony Cooper, a managing director at Arkley Brinc. "We will always ask how the founders have validated the concept and what kind of testing have they done. And you need to do a lot of research into the market size and landscape to see potential competitors, even if they're not direct competitors. They could be about to pivot into your space or geographical market."

Arkley Brinc brings together Poland-based VC firm Arkley with Hong Kong accelerator Brinc in a global hardware program that is currently deploying its first $15 million fund as combined entity. Strong priorities around careful end-user targeting are on show in the existing portfolio, which includes the likes of Omni Care, a Netherlands-based smart baby monitor maker, and Hong Kong's Soundbrenner a niche wearables maker marketed exclusively at musicians.

Intensively checking on what the pubic wants, however, can run contrary to the spirit of innovation. As automotive pioneer Henry Ford is often quoted as saying, "If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses." Indeed, the fax machine spent years as novelty tech searching for mainstream demand until it became ubiquitous enough in the 1980s to enjoy a successful run. Given the central role of interconnectivity in modern devices, this example of patiently awaiting critical mass in a networked system may be particularly apt.

The most convincing value-add propositions from VC may therefore relate to helping start-ups recognize when consumer survey responses don't obviously correspond to market behavior and how to address the discrepancy. Most often, this will be through hiring the right talent or connecting with the relevant service provider. As with any engineer-dominated field, getting marketing and business smarts onto the team is important, but in consumer hardware in particular, product design for the world outside the lab must not be ignored.

"One extremely important aspect that almost nobody considers is to make sure the company has user-experience designers who are not engineers because what happens is, you get a product that works but it's really clunky to use and it's not intuitive to people who are not hardware engineers," says Glenn Sanders, a hardware-focused analyst at technology research firm Tractica. "If I were going to invest in a company, I would insist that they hire designers or at least consultants to set up the design for the user-experience."

Mind games

Sanders has about 20 years of experience in Silicon Valley, providing hardware research reports and investment recommendations to a number of VCs and related entities. Acknowledging that bringing in new professionals or third-party consulting can be expensive for cash-strapped start-ups, he identifies ego as one of the main reasons that founder-engineers push back on the idea of integrating design help.

"I've sort of played that [design advisory] role in a number of the companies that I've worked in, and it's often met with resistance by engineers because they think they know it all, but they really don't," he adds. "There are very few people like Steve Jobs, who are good at both. I've worked with hundreds of engineers over the years, and I don't think I've met one who could do both really well."

The psychology here lays bare the fact that consumer hardware as anyone knows it is still going through a transition period that requires a measured, even diplomatic approach. The dawn of the internet and software-laden hardware may have shaken up project economics, but for most stakeholders, business building logic remains locked in the past.

The traditional hardware mindset – that a blueprint must be flawless before proceeding to market – will have to be updated. This is partially because spending too much time locked in the lab lends itself to excessive overdevelopment and overdesign, a phenomenon known as "feature creep." But more importantly, it's because the trial-and-error style of product development more commonly associated with software is now the only way to be competitive in early-stage hardware.

"What we really look for is a team that can iterate with speed. In the hardware space, that sets them apart from other companies," says HAX's Turner. "When you get a perfectionist, they take too long being in love with a particular idea rather than just scrappily building something, testing it, iterating on it, and getting it into the mass market as quickly as possible, knowing that it's not going to be perfect. That definitely tends to work much better because software is such an important element of every hardware product – and it's the software that can adapt and change."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.