US tech regulation: Green card or red card?

Compliance with US regulations on foreign investment in critical technologies is forcing Chinese VC players to examine their fund structure and governance as well as their deployment strategies

Four months from now, broader US regulatory powers that extend voiding rights on foreign investments from change-of-control transactions to encompass minority deals involving critical technologies will be in force. Their impact is already being felt in the venture capital space, where some deals have been delayed, others have gone unsigned, and still more are being unwound.

One advisor received instructions from a Chinese investor to sell a position in a US unicorn based on the following rationale: "Recent conversations with CFIUS [the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US] led us to change our understanding of this transaction. It's fine if more than 50% of the fund's LP base is non-US; even close to 100% is okay, but it can't be Chinese, Russian, or other problem countries. And the GP has to be non-Chinese."

The investor decided to sell the position because it didn't meet the last of these criteria. CFIUS looks through the layers of an investment and establishes whether the ultimate decision-making authority – which receives information on a critical technology asset, oversees its development, and votes on its future – is a foreign entity. In this instance, some of the partners are Chinese nationals. Ironically, one of the bidding groups is another Chinese investment firm, but its principals hold US passports.

The expanded scope of CFIUS is moving from pilot program to statute, following the recent issuance of proposed regulations for implementation of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA). It has created considerable uncertainty, not least among Chinese investors, which are widely seen as the unspoken primary target of the impending legislation. For VCs, this is not just a matter of individual transactions – their entire organizational structure, from the identities of those making investments to governance of their funds, could come under closer scrutiny.

"There is a tremendous amount of ambiguity to these rules, not just at the margins but at the core," says Stephen Heifetz, a partner at law firm Wilson Sonsini who previously served on CFIUS. "Where you have a majority of non-US citizens managing a fund, I think CFIUS would say its controlled by foreign persons. But if three out of five managers are from the US, is the fund controlled by a foreign person? It's harder to say, and CFIUS has not given any guidance on that."

Impending doom?

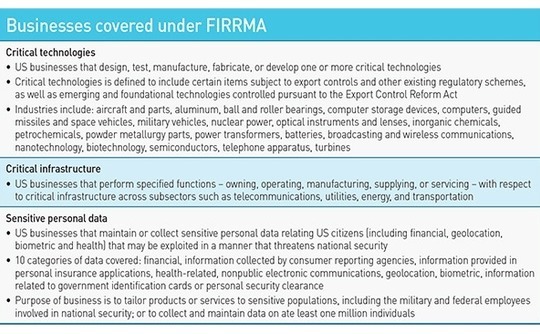

The proposed regulations, which will come into effect no later than February 2020, leave in place the FIRRMA pilot program launched towards the end of last year. They concern companies involved with critical technologies, critical infrastructure and sensitive personal data (TID businesses): specifically, technologies that are subject to export controls; telecom, utilities, energy and transportation infrastructure; and data that may be exploited in a way that threatens national security.

This covers numerous areas of interest to venture capital investors. Computer storage devices, batteries, wireless communications equipment, nanotech, biotech, and semiconductors all appear on the list of 27 critical technologies, while export controls can be used to target additional emerging technology areas. The sensitive personal data criteria capture businesses that collect or maintain data on at least one million individuals, which would include many internet-based services start-ups.

Any foreign participation in a qualifying deal must be disclosed to CFIUS at least 45 days prior to the completion of the transaction. Failure to do so may result in a fine equal to the value of the investment. Most filings receive a response – approval, a request for further information, or a unilateral review if the parties are uncooperative – within 30 days. It is also possible to make a more detailed submission for complex deals that require a lengthier review.

Indeed, many firms are making investments that are not subject to a mandatory filing and hope they don't stand out from the crowd. This approach has resulted in a lot of CFIUS risk allocation language being added to investment agreements, covering issues such as whether the investor and investee cooperate if a filing is requested, on what grounds they could take legal action against one another, and what happens if a divestment is necessary.

"Some larger foreign investors don't mind doing these filings. The view is that they bring a lot of credibility, and the start-up can just deal with it – so they will make the filing and see if it gets approved," says Jordan Silber, a partner at Cooley. "Many others have a different opinion. If it's a hot start-up – one with lots of capital available to it – that fund manager fears getting kicked out of a deal if they tell the company they need 45 days for CFIUS to figure out whether they can invest and that in the filing process they will have to disclose details on the company."

The alternative course of action outlined in the proposed regulations – claiming passivity – might be equally unappetizing for a VC investor that claims to provide strategic support to portfolio companies. In these instances, the foreign party must have no representation on the board or observer or appointee rights, no involvement in high-level decision making within the company, and no access to technical information unavailable to the general public.

Going native

None of this matters if a fund can be structured to participate in deals as a domestic investor, hence the emphasis on the nationalities of management. "If someone told me they had Chinese nationals who want to manage a fund that will invest in US companies with sensitive defense implications, I would say you aren't going to be able to do it under current law or under any anticipated evolution of the law in the near future," says Brian McDaniel, a partner at Wilson Sonsini.

Where there is a mix of US and non-US nationals among the key persons, ambiguity reins. Some firms that invest in China and the US – and whose teams comprise US and Asian members – have responded by exploring separate funds for US investments. GGV Capital is among the more high-profile firms that fit this profile and the structure has been considered though not yet acted on, according to a source familiar with the situation.

These vehicles are typically domiciled in Delaware rather than the Cayman Islands, the LPs are all based in the US, and the non-US partners are excluded from management. Silber warns that regulators may probe for evidence of true separation between the flagship global or China fund and the dedicated US entity. If the latter vehicle makes an investment in a critical technology area and there is no filing, but then it emerges that the two teams have been sharing information pertaining to the US-based portfolio company, CFIUS might rule that the deal must be unwound.

"We would counsel true separation in a documented and verifiable manner," he adds. "This means having a separate email server and holding separate investment committee meetings, among other things."

While the proposed regulations are lacking as to what constitutes a foreign investor at the GP level, they offer more clarity on the treatment of foreign LPs. There is an acknowledgement that even LPs with advisory committee seats have no control over the fund provided they do not participate in investment decision making or have access to non-public technical information pertaining to specific portfolio companies. Investments made by the fund would therefore not qualify for disclosure.

However, issues surrounding foreign control at the LP level are arguably more nuanced. It goes beyond the fund-of-one or co-investment structures in which there is clearly no passivity – because the LP has direct influence over management or direct exposure to sensitive assets. If the fund terms dictate that 80% LP support is required for GP removal, a foreign investor could make unilateral change if it accounts for over 80% of the fund or veto changes proposed by others with 21%.

"The GP might be a US person, but with a no-fault removal clause and LP base that is primarily non-US persons, the LPs could effectively be in control of the fund once the GP is removed," says Alice Huang, a partner at Morgan Lewis. "Although these are market terms, when you look at the fund's investment strategy, you may have to look further at the rights given to LPs."

Playing safe

CFIUS has given no indication as to what percentage fund ownership would be acceptable for LPs from different jurisdictions. Advisors say the widely accepted minimum threshold of at least 50% US money is rooted in a perception of safety rather than any legal reality.

At the same time, some firms have taken the more substantive action of reinforcing their fund documentation. These include rights to withhold information from LPs and/or exclude them from votes if it is determined that sticking to the status quo might inhibit the fund's ability to make a certain investment. Huang adds that more thought should go into operational processes such as what happens in the event of GP removal – finding a replacement manager that would continue to meet the GP exemption or winding down the fund – in order to minimize disruption.

Second-guessing regulations before they have been implemented is never easy, but the CFIUS situation is complicated by uncertainty as to how aggressively the organization will wield its additional powers. Its track record of vetoing new deals, investing and unwinding those where filings were not made is sparse.

"If you replaced a CFIUS compliant GP with one that is not compliant, they would have the ability to unwind that transaction," says McDaniel of Wilson Sonsini. "But would they notice? If it was a major defense provider with a capitalization of hundreds of millions of dollars, they probably would. If it's a $2 million company in an area the defense industry isn't tracking, probably not."

SIDEBAR: US inflows - Hard to access

Ray Dalio envisages a disconcerting scenario for the deterioration of US-China relations. In a recent essay, the founder of Bridgewater Associates draws parallels between the present socioeconomic climate with that of the 1930s, characterized by the convergence of three forces: widening gaps in wealth and political ideology, brutal monetary policy, and the rise of a power to challenge the US.

On the US-China dynamic, Dalio notes there is historical precedent for trade wars, technology wars, geopolitical wars, and capital wars. The first three are already underway to varying degrees and he detects early strategic positioning in the fourth. Specifically, Congress is already considering measures that would delist Chinese companies from US exchanges for failing to meet audit requirements and restrict the Federal Retirement Thrift from investing in Chinese stocks.

"The ability of the US president to unilaterally cut off capital flows to China, freeze payments on the debts owed to China and also use sanctions to inhibit non-American financial transactions with China must be considered as possibilities," Dalio adds, in reference to the suggested use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act. Just as the US wants to limit the flow of Chinese capital into US technology, it may end up trying to stop American money moving in the opposite direction.

While these discussions remain in the realm of the hypothetical, anecdotal evidence suggests it is getting harder for Chinese VCs to raise money out of the US. However, this should not necessarily be seen in the broader context of US-China tensions.

"There are unrelated questions of saturation and performance," says Javad Movsoumov, an executive director in the private funds group at UBS. "The market is in fatigue – a lot of funds have been raised in the last 15 years, there's a lot more choice, there are a lot of re-ups. And when you consider the results for a very broad population of funds, they are disappointing, especially when it comes to distributions compared to North American funds. China funds that attract attention typically have differentiated strategies backed by strong realized returns."

Capital commitments to US dollar-denominated China venture funds stand at $4.9 billion so far this year. It is unlikely to match the $13.1 billion raised in 2018, but the historical trend of the market is one of peaks and troughs – reflecting the fact that a handful of top-tier managers raise large sums at short order, while many others struggle. Those top-tier players often have an established following of US institutional investors that aren't looking for new relationships.

"The bar is high for allocations to relatively young or emerging venture funds in China. Many of the more mature LPs, the endowments and foundations in particular, who might be natural buyers of the risk-return, have been in the market for a long time and they have their trusted managers. These are fairly mature LP investment programs, which may be consolidating by number of GPs and not looking to add much else," says Nick Miles, head of Asia and Europe in Lazard's private fund advisory group.

Chuan Thor, who founded AlphaX Partners in 2016 after more than a decade with Highland Capital Partners, adds that perceptions of China risk – regardless of manager strategy – vary by LP type. While pension funds have become wary of the country given the prevailing geopolitical conditions, endowments and foundations are generally not put off. Moreover, any investor with zero direct exposure to China is unlikely to be executing an aggressive expansion plan.

There is also variety in how LPs explain decisions not to commit to a fund. One advisor recalls only one instance in the past year in which US-China tensions were explicitly cited – and then the LP invested in another China GP within the same timeframe, suggesting the tensions could have been a helpful excuse.

Another advisor identifies two common knockbacks, neither of which does much to hide the sentiment. The first: "My investment committee is composed of a lot of different stakeholder groups and they are currently not comfortable adding allocation to China given the current macro considerations." The second: "Markets are adjusting, so this could be an interesting opportunity, but we don't see an end in sight. Therefore, we want to wait until there is more clarity."

Despite the current political rhetoric – and the fact that some Chinese managers have been denied visas to the US – few industry participants expect the significant flows of American money into Chinese venture capital to be cut off. However, those taking a long view might consider the virtues of geographical diversification within an LP base. "Are these guys now spending more time in other markets? Absolutely," says Vincent Ng, a partner at Atlantic Pacific Capital.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.