Sovereign investors and technology: Smart nations

Conservative sovereign wealth investors are increasingly comfortable making direct commitments to venture-oriented technology companies. The strategy appears to suit them but remains to be validated

At first glance, GIC Private's commitment this month to acquire a portfolio of data centers across China appears a straightforward play on the supply-demand gap for computing capacity and the scalability advantages of digital infrastructure versus traditional projects. But it could be much more.

The Singaporean sovereign wealth fund (SWF) has agreed to take a 90% equity interest in an unspecified number of data centers in lower-tier Chinese cities as part of an agreement with specialist developer GDS Holdings. It is not just a matter of shoehorning SWF real estate capital into the world of innovation – the deal confirms that sovereign-style goals and methods can, and do, blend seamlessly with advanced technology investing.

It is not clear to what extent GIC's technology team advised the GDS partnership, but the firm does employ a real estate professional in its technology investment unit specifically to help with crossover deals. Indeed, this is a key area of focus for the SWF, which recently made real estate the theme of its Bridge Forum, an annual conference series that explores industrial tech disruption by bringing together GIC's Asian financial contacts with Silicon Valley luminaries.

This kind of activity does much to reveal a distinct "venturization" of SWF strategy in recent years, but the trend is not happening in a bubble. The idea that more conservative ends of the alternatives space, such as real estate, are overlapping with tech can be seen in Amazon's move to operate supermarkets and insurance tech unicorn Oscar Health opening brick-and-mortar clinics. Sideways shifts of this kind would have been hard to predict only a few years ago, but they match well with SWF money.

"For GIC, our most important differentiator is our ability to identify category-creating companies globally where we can be selective and have lifetime relationships with founders, regardless of the valuation environment," says Chris Emanuel, co-head of GIC's technology investment group (TIG). "An IPO is not necessarily a trigger for GIC to divest either. This differentiates us from other VCs and positions us well as a long-term investor."

Emanuel is based in the US, and TIG maintains bases in India and China, revealing an increasing recognition among SWFs that the ecosystem building entailed in tech investment cannot be done without branching out. Sovereigns have taken on new alternative asset classes in the past, with the typical learning curve progressing from real estate and infrastructure to private equity and credit, and eventually venture. Teams will eventually be built up and expertise gained, but technology-focused VC may prove harder in the long run since incumbent competitors are relatively more specialized.

Singaporean stars

Uptake typically begins with co-investment programs alongside existing GP partners, then more ambitious investment matching schemes, and on to direct deals and the opening of foreign offices dedicated to technology connection-making. This process took GIC about 15 years. Along with Temasek Holdings, it has made Singapore the clear leader in the movement to date. The two groups began investing directly in a significant way around 2012. Before that, there were never more than 10 direct tech deals made by SWFs globally a year.

The prevailing theory behind the Singaporean head start is simply that the government's strong fiscal position provides freedom to experiment. At any rate, other state funds have gradually followed with a range of motivations. These include a desire to explore how new technologies will impact traditional SWF assets – such as what 3D printing means for ports – as well as more familiar drivers pushing investors into private markets, including low interest rates, the success of VC in recent years and the fact that start-ups are delaying IPOs longer. Meanwhile, growth in both co-investment experience and the cost of intermediaries has inspired more of the deal making to go direct.

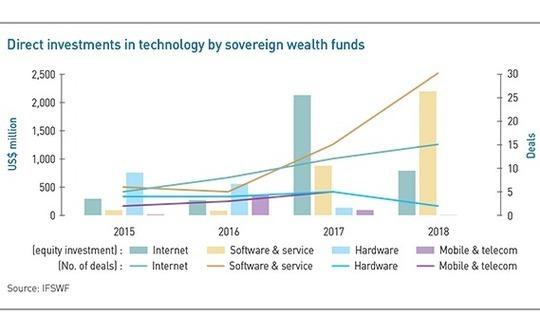

The biggest contributing factor, however, may be that several development areas related to online and enterprise technologies have become de-risked. SWF direct investment in internet and software has spiked dramatically since 2016, according to the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF), while hardware and mobile categories have floundered. Software has seen the most impressive uptake, with SWFs' direct investments globally jumping from $91 million in 2016 to $882 million in 2017 and $2.2 billion last year.

Series A and B-stage transactions were a big part of the momentum, more than doubling in volume during 2018 to 20 deals, 13 of which were either led or co-led by the participating SWF. "The majority of SWFs that are mature enough to invest in early-stage companies are now doing so," says Victoria Barbary, director of strategy and communications at IFSWF. "You will continue to see investments, but we will get to a point where they have reached their target exposure and this type of activity will slow. This trend could be measured in months or years."

Beyond IRR

The trend toward earlier stages can be explained to some extent by the natural risk-reward inducements of being ahead of the game. But there is a growing sense that SWF interest at this end of the VC spectrum betrays a stronger devotion than previously assumed to the so-called double bottom line. In this scenario, national interests can guide investments as much as financial returns, especially where one-dimensional economies are in serious need of innovation such as the oil-dependent states of the Middle East and primary industries-focused Australia.

"Any SWF will tell you that financial returns are their first mission, but many add another layer with the most visible logic around knowledge transfer and economic development," says Javier Capape, director of sovereign wealth research at IE University. "Those are goals that a traditional pension fund, asset manager, private equity or venture fund would never have. This is what makes sovereigns different. For them, investing in technology is not just to diversify their portfolios, it's to help diversify their economies and hedge against the risk of industry disruptions."

Most of the nerviness on this point is directed at the more bullish Middle Eastern SWFs such as Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund and the United Arab Emirates' Mubadala Investment. Despite being followers behind Singapore, these two SWFs are recognized as the most ambitious globally in terms of venture, having contributed $45 billion and $15 billion, respectively, to SoftBank's $100 billion Vision Fund.

Mubadala may be the more conspicuous in its national agenda, with a formal plan to woo Vision Fund portfolio companies into opening regional offices in Abu Dhabi's Hub71 technology park. Earlier this year, it also threw its weight behind an Abu Dhabi-based crypto exchange called MidChains in what is seen as a response to similar investments last year by both Temasek and its VC arm Vertex Ventures.

These moves offer a reminder that SWF investment in speculative technology areas may be best managed with an eye on geography. If a double bottom line of financial returns and economy building is the plan, the decision to co-invest, lead a deal or participate through fund commitments can depend on the mix of access points in the targeted jurisdiction. Queensland Investment Corporation (QIC), an Australian SWF, follows this philosophy by limiting its direct, early-stage technology investment activity to its home state.

QIC has allocated A$80 million ($54 million) to an early-stage development fund that exclusively targets companies headquartered in Queensland. Investments are only made when a separate qualified VC also participates, in which case the commitment is matched and the VC will have the right to buy out the QIC position within a few years. The idea is to be flexible, allowing the SWF's later-stage operations in the US to benefit from synergies with the early-stage portfolio, while supporting jobs growth and broader economic development on a grassroots level at home.

"As sovereigns go direct in technology more, they're finding it hard to consistently invest $100 million in any given deal, so there's a need to think differently about cost of capital," says Zach Jackson, an investment director at QIC. "If you think about something from just an economic standpoint and it doesn't meet that bar, it doesn't mean it's not a compelling or interesting investment. That's becoming more a feature of the market as bigger investors come in. We're fortunate that we can fly under the radar with the capital to be material but the flexibility to be selective."

The long haul

Managing exposure to technology by balancing co-investments and directs through gradual combinations of the two will also require SWFs to understand the changes in volatility that come with closer approaches to young companies and less developed technology segments. Likewise, a cultural change around ecosystem engagement and understanding the timeframes of the VC universe will be important ingredients to surviving any pending shakeout from the boom.

"How long it takes to get capital back into your portfolio is a big consideration as a sovereign," says Jackson. "A lot of long-term investors that have had great success in technology are sitting on parts of their portfolios that are doing really well but are still locked up, and the cash hasn't come back. You do have to have a stomach for not being able to reallocate an investment into something else for a while if you want to be long on innovation."

Another timing aspect of direct VC investing that might be counterintuitively difficult for long-term investors is the extended nature of the stakeholder relationships. Most SWFs with venture programs are quick to point out that supporting a portfolio company from its early days all the way through its post-IPO operations is one of their key strengths. But for sovereigns that have equally long relationships with GPs through fund commitments, there could be structure, commercial, and even legal issues down the track.

Instances where this issue heats up include when SWFs create direct investment portfolios out of the mature businesses that have been developed by their partnering GPs. The logic is that the SWF already understands the sector, the company, and how to take it to the next level. The downside is that the GP has a fiduciary duty to maximize value at exit. The trials of trying to find an equilibrium here are unlikely to suppress the direct technology investment trend too thoroughly, but they will become increasingly necessary to manage with care, which could require additional resources.

"If the end point of this trend is that SWFs exit LP structures and just do direct deals, that's fine, but this is a multi-decade process where there will be parallels, and anecdotally, I'm seeing a convoluted web forming of crossover relationships with external managers that don't add up," says Elliot Hentov, head of policy research at State Street Global Advisors. "I don't think there's been any problems in the marketplace yet, but if this trend grows, I think you're going to see conflicts of interest."

It is difficult to forecast what patterns might emerge around these conflicts as they begin to complicate sovereign agendas partially because there is no clear correspondence between sophistication in technology investment knowhow and sophistication in overall portfolio governance. Most SWFs have some kind of tech team, if not a VC team, but perceptions around the competence of state-level investors in tech varies significantly, especially when a decision is made to move fund commitment professionals into the very different world of a directs program.

"The more sophisticated SWFs recruit from essentially the same talent pool and pay market rate compensation and even have value creation teams, so it would be strange to expect them to get terribly different returns from private equity," says Andrew Thompson, KPMG's head of PE and SWFs in Asia. "Less specialist SWF teams tend to look for other signals in technology like co-investing with well-known names. That's a perfectly valid style, but it also sometimes means repurposing in-house people who are less experienced in tech, and I would expect a fairly clear performance relationship between SWFs taking that approach and the ones hiring from the top tier."

Growing pains

Talent is one of the key constraints for SWFs entering the tech game, but it's by no means the only. Some of the most common bottlenecks derive from minimum check size requirements, difficulties around sporadic investment committee meetings, complex team travel schedules, decision making bureaucracy, and a lack of networks in relevant segments. Most of these concerns are highly labor-intensive and have naturally created demand among sovereigns for outsourced capabilities in the form of specialist consultants.

Potentum Partners, an advisor that helps long-term investors optimize their PE programs in areas such as VC and tech, is tracking this trend closely. The firm was co-founded last year by Steve Byrom, who previously served as head of PE at Future Fund, an Australian SWF that ramped up a substantial tech program under his watch. He finds that as competition for the best opportunities pushes investors toward the high-volume strategies of the earlier stages, challenges begin to multiply in terms of implementation, organization structure and internal resources.

"When you end up writing a lot of small checks, that impacts all the support functions in an organization because you've got far more line items on the balance sheet," says Byrom. "Those have to be monitored, managed, reported on and valued, so it impacts every team, including the guys doing tax and legal work. I know of one organization where they started going down this path and the back office was up in arms over the amount of extra work it created."

The success of investors like Future Fund and Singapore's leading SWFs have to some extent substantiated VC and tech as a sensible part of the sovereign playbook, at least conceptually. But there is a nagging sense among most industry participants that a reckoning is set to happen within the next 10 years, when unicorns will begin to fail, and long-term capital will retreat. Survival in such a case will be a matter of embracing the heterogenous and flexible nature of the SWF space by finding that elusive formula for mixing an aggressive tech agenda with defensive patience.

"In this climate of high valuations, we believe it pays to be cautious and selective, and we do this through a bottom-up selection process, using the same long-term, fundamentals-based approach as the other asset classes we invest in," says Jeremy Kranz, co-head of GIC's TIG unit, noting that his team aims to balance value-creation expertise with an understanding that technology is not a solution to everything. "This is where we focus - mastering not only our ability to assess the opportunity that tech enablement offers but also our understanding of its limits."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.