Women in PE: Mind the gap

Gender diversity within private equity is an increasing priority for LPs and GPs alike. Addressing problems around the recruitment and retention of women requires fundamental changes in culture and mindset

The private equity firm's personnel were arranged in hierarchical formation, three partners at the center and a phalanx of associates and vice presidents. All male. This was a due diligence meeting, part of a protracted pitch by the manager – an Asia-based, country-focused GP – for funding from the International Finance Corporation (IFC). Ralph Keitel, a principal investment officer at IFC, asked the obvious question: Where are the women?

There followed a barrage of excuses: we're trying to hire more women but without success; we advertise positions, we give precedence to female candidates, but they don't accept our job offers; and those that do end up leaving after two years.

"Look at yourselves: Senior management is all male, so there are no role models for women. Look at your working hours: Can a mid-level female have a child and reconcile work and family? Look at your hiring process: Do you appreciate the differences between interviewing a male and a female for an associate position?" Keitel recalls of his response. "They hadn't thought about these things. We want to see a willingness to change and a recognition of what must be done to drive change."

Diversity – of which gender is part – has always featured in IFC's environmental, social and governance (ESG) analysis, but in recent years this focus has become more explicit: if there are no women in senior positions, questions are asked as to what is being done to redress the imbalance. Other LPs are beginning to take a similar approach, albeit gradually.

It is a notorious and complicated issue. The gender imbalance in private equity, as in most of financial services, is plain to see. Yet it encompasses a multitude of considerations, cutting across geographies, strategies and job functions, and taking in everything from practical, day-to-day challenges like the availability of childcare to societal questions about a woman's role in the home and the workplace. There is one area of general agreement: change, if it is to happen, must be led from the top.

"You can tell by talking to leaders of the firms if they really care about the topic and if they see it as a true imperative for their business or whether they paying it lip service in both their words and actions," says Crystal Russell, a principal at QIC, an investment manager owned by the Queensland government. "It comes back to culture and seeing it in action. Are the foundations in place for women to be successful? Is that evident in the interactions you see? We are very focused on the culture of partnerships and whether they are collaborative, transparent and inclusive."

Gender by numbers

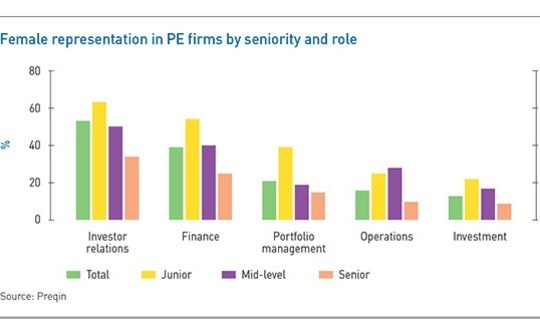

Of all the private markets asset classes, private equity has the lowest proportion of women globally with 17.9%, according to Preqin. Venture capital is the highest with 21.1%. Female representation is skewed towards non-investment functions. Women account for 53% and 39% of employees in investor relations and finance, respectively, but just 13% in investment. The numbers also thin out with every upward movement through the pay grades – from 31% in the junior ranks to 10% at senior level.

In Asia, women make up 18% of the private equity workforce, roughly in line with the rest of the world, but the region tops the standings for representation at mid and senior levels. Women occupy 14% of senior positions in China and 13.8% in Hong Kong, compared to 9.5% in the US. However, the region is diverse in its levels of gender diversity – Korea is on 3.7%.

Preqin doesn't offer country breakdowns by job function. IFC provides some insight, noting that 11% of senior investment professionals in emerging markets-focused PE and VC firms are women versus 10% in developed markets. China leads the way on 15%, with 64% of firms having female participation in ownership. The comparable statistics for South Asia are 7% and 18%.

Most global GPs with a sizeable Asia-focused funds – Bain Capital, CVC Capital Partners, and KKR – were not forthcoming when asked for the level of female participation in their local deal teams. TPG Capital and The Carlyle Group gave figures of nearly 30% and 18%, respectively; the latter added that 15% are in senior roles. Neither disclosed the absolute numbers of professionals. At Baring Private Equity Asia, which has about 100 investment professionals across PE, real estate and credit, and Affinity Equity Partners, which has a 45-strong team in private equity only, the share is 20%, industry sources said.

Numerous firms are taking proactive steps on diversity in recruitment. Carlyle recently set some aspirational targets, including of having two diverse candidates interviewed for every role. Whenever a team comes up short, it must show that steps were taken to assemble a diverse shortlist. "We also provide training for individuals who conduct interviews to ensure we are using best practices," says Kara Helander, who took up the newly created role of chief diversity officer at Carlyle last year.

Affinity is said to have introduced a formal diversity and inclusion (D&I) policy at the start of the year. The focus is on diversity in terms of background and experience as well as gender, but it includes a target of hiring at least one female professional into each office by the end of the year. Other firms have similar objectives, says Neil Waters, Hong Kong head of recruitment firm Egon Zehnder.

"If a client wants diversity you will constrain the search to yield that outcome, assuming there are people who are diverse and capable - and that is a reasonably safe assumption in modern society in almost every endeavor," he explains. At the same time, no one wants to go so far as to introduce quotas for fear of diluting the talent pool. Waters adds that some of his PE clients would overlook a more qualified male candidate if presented with a female one who met the criteria for a position while others would not. Both diversity and capability have value, the question is what value is placed on each.

This dilemma is shaped by the depth of talent at a private equity firm's disposal. While there is a general appreciation among GPs about the importance of diversity when making investment decisions – as well as a growing number of studies that show a positive correlation with performance – a common complaint is the limited supply of qualified women, especially at the senior level.

Asked why there are so few women in Korean private equity, one local GP blames the male-dominated corporate sector. It is very difficult to groom female investment bankers and PE professionals in an environment where deal sourcing hinges on being plugged into school and business networks predominantly populated by men and the counterparties in almost every transaction are male. Most new hires come from investment banking, which exacerbates the problem.

Recruitment channels

There is a general reluctance among GPs to stray beyond the traditional recruitment channel of investment banks. "The consulting firms do a better job of recruiting women but teaching them is a real challenge – most of them don't have the financial modelling and analytical skills that we look for," another GP explains. "We hired one woman from an accounting firm, and while she's been great, it took at least a year for her to get to the level she would have been at had she come from a bank."

This manager has fewer than 20 investment professionals and his sentiments are echoed by other mid-cap players. "I believe we should be recruiting from a broad range of sources; I would love to hire an ex-lawyer or someone who has worked for a corporate," says K.C. Kung, founder of Greater China-focused Nexus Point Capital. "But smaller firms don't have the resources to train people up and wait for them to mature. Established GPs can take that risk and hire people with less of an investment background."

The broader perspective is that difficulties are worth it if they provide an additional edge. Private equity requires an array of skillsets, not all of them developed sitting in front of a computer screen. There is also a sense that homogeneity in background and capabilities can lead to missed opportunities. China consumer is the most commonly cited example. The kneejerk response from some LPs on seeing an all-male China investment team is to question how they can build knowledge and insight into such a rapidly evolving market, where women have most of the spending power, without input from women.

Russell of QIC adds: "When I started in private equity over a decade ago, I recall seeing a lot of bios and most people had been to a few common business schools and worked at a handful of investment banks or consulting companies. Today, given what you need to do to generate value, if everyone in your team has the same way of thinking, the same training, the same network, you may miss out on interesting sources of deal flow and an ability to add value and bring something different to the table."

Asian venture capital is more diverse than private equity in part because there is no systematized entry route. Australia-based OneVentures, for example, hires from M&A, corporate advisory, and strategic consulting as well as bringing in entrepreneurs. As a female-founded firm, gender balance is important, but strong female representation is more a function of a broad recruitment strategy intended to meet the needs of start-ups light on management talent, according to Michelle Deaker, a managing partner.

Based on accounts of the wealth of female talent moving through the ranks of investment banks in Asia and into PE firms, GPs may soon have plenty of qualified and diverse candidates available for interview. A bigger challenge is making sure they don't leave halfway through the long journey to seniority.

Given the apprenticeship nature of the asset class, it could take more than a decade for a recent recruit to make his or her imprint on leadership. Pacific Equity Partners (PEP) is a case in point. The Australian buyout firm has an investment team of approximately 30, including a dozen managing directors, all currently male. It doesn't make lateral senior hires into the PE team, preferring to recruit a couple of analysts each year. Four women have joined in the past five recruitment cycles, about 40% of the total intake, but they might not break into the managing director group until 2030, assuming they stay.

"Our number one priority is to produce excellent outcomes for investors. This brings with it a related priority, which is to recruit the very best people that money can buy; by definition that must include more females. We are working hard to achieve this organically," says Tim Sims, a co-founder and managing director at PEP. "What we have seen within our existing cohort of females has been relatively higher turnover based on legitimate personal and family priorities that have emerged."

Talent management

A certain amount of turnover is inevitable in the junior ranks after about three years, when the first phase of the apprenticeship finishes and promotions, salary and bonus hikes, and a taste of carried interest are awarded. This is also when some employees pursue MBA programs. Female departures are not necessarily so concentrated and motivating factors are often tied to changes in family circumstance, such as starting a family, caring for an aged parent, or relocating due to a spouse's work.

In some respects, younger private equity firms have it easier when trying to boost female representation – at two-year-old BGH Capital, women account for eight out of 18 executives overall, at two-year-old Nexus Point it is three out of 10 – because they can prioritize a healthy gender mix from day one. However, issues around retention are still there.

"It can be difficult committing to a fund that lasts 10-12 years, especially when you're at or around the managing director level. You must put in money, see through deals, and stay through the life of the fund; that's a big career decision. Maybe it is harder for females to make that kind of decision," says one senior female executive. And once women step off the investment track, it is difficult to step back. Moving into a COO or IR role is not uncommon.

The increased focus on diversity in recent years has resulted in the publication of assorted guidelines and best practice notes. Flexibility is central to these efforts, whether it is parental leave policies – an IFC survey found that nearly a quarter of GPs do not offer maternity leave and over half don't offer paternity leave – or allowing employees more autonomy in choosing when and where they work with a view to fostering a healthier work-life balance.

Numerous private equity firms already have flextime policies. At some larger firms – such as Carlyle and TPG – these are part of D&I initiatives driven by the CEOs and senior women executives that encompass everything from training to support networks to easing transitions back into the workplace after lengthy absences. However, it is unclear whether flexibility is as ingrained in private equity as other areas of financial services, almost to the point where it is the norm rather than the exception.

"There are plenty of other professions that have managed to crack the code on flexible work arrangements. Law firms and consulting firms, for example, have consciously put in place structures and processes so as not to discriminate against part-time work," says Waters of Egon Zehnder. "It involves a lot of mutual understanding and empathy and a different way of working. It will require a reasonably enlightened firm to do that in a competitive transaction-based environment."

Bain & Company has three different flexible working models. The first is a leave of absence, which ranges from a one-off break of unspecified length to recurring absences of one or two months a year. The employee receives salary across the whole 12 months, but as a pro rata portion of the full sum. This is trickier for partners because they are responsible for multiple projects that must be handed over at the same time, but it has proved workable.

A second option involves rotating into a role that requires less travel – typically focusing on a certain practice area or internal knowledge building – for a set period, while a third retains the client-facing functions but dials down the time commitment. The employee works three or four days a week as part of a job share with a colleague. While there must be some room for compromise to accommodate key meetings and project deadlines, the goal is to allow someone to do the same job with lower intensity.

Yaquta Mandviwala, a partner who leads the Women in Bain program for Asia Pacific, declines to comment on the applicability of these models to PE, but she stresses that successful implementation relies on a change in mindset. "If you face losing some of your stars because you cannot offer flex policies, you find way to make it happen," Mandviwala says. "Talented people don't always want to work on a monotonous basis, they want to thrive and bring the best of themselves to work."

Ingrained prejudice

It is worth noting that these programs are not gender specific – it could be argued they are a response to wider disruption of the workplace environment. Younger generations are not necessarily interested in a job for life; there is a desire to rotate the experiential and the occupational, which could mean taking 10 months out to start a family or two years out to work for a non-profit organization.

This is welcomed by women in private equity who see male involvement as essential to the drive for greater gender diversity. "It's not just about women and it's not just about children. It's about a work environment that is fit for our century," says Judith Li, a partner at Lilly Asia Ventures. "Too much emphasis is placed on childbirth because it is the first point that comes to mind for most people."

Indeed, children and perceptions around working mothers sit at the heart of the sociocultural issues identified by numerous industry participants as the biggest diversity challenge in Asia. A report released last year by Hong Kong's Equal Opportunities Commission – which was not specific to private equity – captures the mood. When local employers were asked about their ideal job candidates, less than half of respondents expressed a willingness to hire women with children.

Responses to the "stigma of motherhood" can be extreme. Some women self-select themselves out of careers in financial services before they start because they don't believe it is conducive to family life. Others overcompensate on returning from maternity leave – if they ever really left at all.

Several PE executives interviewed for this story claim not to have missed a single call or email during their maternity leave and kept up a schedule of meetings, citing the limited resources of their firms and a feeling that they needed to prove a point. "You must go out of your way to prove that you are as good as the guys and working as hard as them. You don't want to be the person who they say had a kid and is now never available," one explains.

Fiona Nott, CEO of The Women's Foundation in Hong Kong, notes that some women oppose family leave policies as they reinforce the stereotype that mothers can't focus on career development. Conversely, studies have found that employers favor fathers over childless men because they are viewed as more stable. Upending notions around the gendered nature of work and housework requires wholesale cultural change and a "solution that applies across the board to men and women," Nott says.

These challenges underline the importance of female role models and mentoring programs in demonstrating that gender-related obstacles can be overcome and in giving junior executives access to experienced industry professionals who can offer guidance on career development. But addressing diversity in private equity involves male buy-in as well, whether that is from superiors in the workplace or family members in the home.

LPs can also play a role by recognizing warning signs when they see them. "If a manager doesn't have a diversity policy or doesn't agree that diversity is beneficial to the industry, that is clearly an indication of wider team issues," says Juan Delgado-Moreira, vice chairman at Hamilton Lane. "If you don't worry about diversity in decision making, this implies you don't worry about many things – women, non-partners, lack of participation in the investment committee. These issues don't come in isolation."

SIDEBAR: Performance: The diversity premium

"My view is that diversity makes for better investment decision making. Given 50% of the world's population are female, there are lots of businesses where women will have different insights and perspectives to men. I suspect a lot of deals that didn't turn out too well would not have got done if there had been more female voices around the investment committee table."

Versions of this statement have been made frequently enough in Asian private equity that it is unfair to make direct attributions. Two studies released in 2019 offer supporting evidence.

The International Finance Corporation (focusing on data from 700 PE and VC funds in emerging markets only):

• Gender balanced funds – where female representation in the investment team is 30-70% – realized excess net internal rate of return of 1.7 percentage points greater than male- or female-dominated funds. When normalized for the median IRR of emerging markets, gender balanced funds outperformed unbalanced funds by as much as 20%

• In terms of total value to paid-in (TVPI), gender balanced funds had a median excess return of 0.17x, compared to -0.01x for unbalanced funds. The median outperformance is 13%

• Better performance among balanced funds is primarily driven by enhanced investment decision making and expanded deal sourcing through broader entrepreneurial networks

• The trend bears out across venture capital, buyout and growth, and real assets

MVision and HEC Paris (focusing on deals completed by 220 funds in North America and Europe between 1986 and 2015):

• The gross IRR and TVPI for a gender diverse investment committee (based on the deal leaders in a firm at given times and assuming at least three people per committee) are 32% and 2.52x. For all-male investment committees, it is 20% and 2.0x

• The failure rate for diverse committees is 12% (based on the proportion of deals within a given year that delivered a TVPI below 1.0x) compared to 20% for all-male committees

"Having a gender-balanced team isn't just good business but smart business, because more balanced teams outperform. An increasing number of investors recognize this," says Ralph Keitel, a principal investment officer and regional lead for funds at IFC.

SIDEBAR: Mentoring: Two-way street

Few people in financial services dispute the basic benefits of mentorship. For Haide Lui, now head of investor relations at Ascendent Capital Partners, access to senior female executives was essential to her development during an earlier stint in banking. These seasoned individuals showcased a range of different strategies for prevailing in a male-dominated environment. But solidarity was the key.

"It's important to be able to talk to senior people, tell them that life is rough, and ask them how they did it. You want them to say, ‘You probably feel like dying, but you'll pull through – it's going to be fine, just look at me,'" says Lui. "Even the most successful people have broken moments. Seeing evidence that they overcame them gives you confidence that you can as well."

Mentorship programs that pair up junior female employees with senior male or female counterparts have been established internally by private equity firms themselves as well as by industry associations such as the Australian Investment Council. However, it is important whether mentorship is the most appropriate structure based on the objectives of different initiatives.

"So much emphasis is placed on matching up folks and the development of a long-term relationship. If this does happen it is healthy, but it's difficult to achieve perfect chemistry. The strongest mentorship relationships I have seen have been between professors and students and between bosses and subordinates, who have interacted closely for a long period of time and developed trust," says Judith Li, a partner at Lilly Asia Ventures. "Trying to match up people artificially usually doesn't work."

She sees more potential in formalized coaching, for example bringing in professionals who can educate women in certain areas. This might include sessions on negotiations with employers, given the tendency to take a less aggressive approach than male counterparts and underplay their contributions.

Others also highlight the potentially detrimental impact of poor matching, emphasizing that it is the responsibility of junior employees to be thoughtful in how they seek out mentors. One female LP argues that mentorship is more effective starting at principal level because mentees are more aware of themselves and looking to take on a broader range of responsibilities. In the early years, it is more about basic approaches to work.

"The assumption is that it's straightforward – help me answer questions, tell me what path I should take," the LP explains. "But any relationship that is one-sided won't last long. When you ask for input from senior professionals, you must think about what you bring to the table that makes it more interesting for them."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.