China-US decoupling: Silicon curtain

Evidence is mounting that US and Chinese ecosystems for advanced technologies are careening toward an antagonistic decoupling. Investors are philosophical and pragmatic

Trade tensions have been on a boil for long enough now that even attempts to cool things down appear to cement the idea that an irreversible schism has already been put in motion. In the latest twist, talks at the G20 summit in Japan signaled there will be an easing of US business restrictions against Huawei, the Chinese telecom giant considered a cyberespionage risk. But it may be too late for vague commitments to a vanishing status quo.

Part of this is political. The Huawei ban has helped reveal that a hawkish brand of realpolitik – which has been rising for decades in step with China's overall growth – is now the dominant school of thought in the US security establishment. Hardliners are well represented in both major political parties, and with national elections looming, it was perhaps inevitable that pushing for a truce in the trade war would entail a certain amount of blowback.

There is, however, a more fundamental reason the genie cannot be put back in the bottle so easily. Huawei's emergence as both a leading data player and the most contentious flashpoint in China-US relations is not a coincidence. Indeed, it clarifies that the trade tensions are most crucially about achieving advantage through technology. This has in turn fueled the theory of decoupling, whereby a Cold War-style unwinding of economic cooperation plays out on a number of levels, but especially in the deep-tech domains that are increasingly associated with national security.

Huawei is also the symbol of tech decoupling because it has seen a tit-for-tat conflict of surgical licensing hurdles, investment restrictions and tariffs escalate into a new vocabulary of blacklists and infrastructure-level prohibitions on cross-border business. On the China side, this has included credible speculation about a retaliatory embargo on the export of rare earth metals, which are essential to many digital industries.

Misplaced confidence?

For investors, the decoupling threat spans upstream equipment access and operational issues, talent acquisition, overseas investment and M&A, as well as fundraising and exits. In addition to telecom, data-driven technologies likely to be swept up in the trend include artificial intelligence (AI), autonomous vehicles, and crypto-related sciences. China does not have a history establishing internationally competitive standards and infrastructure for intangible industries of this kind, but many investors in the country remain confident.

"Maybe a China-only system will be created, but that wouldn't necessarily be so bad for investors because there will be more chances to invest in things like mobile operating system supply chains," says Wei Zhou, founder of China Creation Ventures. "I think there will be more fragmented systems, which will have a significant impact on companies that want to go global because they will need to operate on different systems. But for a lot of companies, the increase in operating costs will not be too difficult to overcome. In the end, I think it will create new opportunities for Chinese start-ups."

Optimism for tech ecosystems in a decoupled world stems in part from the fact that digital industries have always coped with a lack of universal standards, even in difficult-to-access economies. China's mobile operating system (OS) market, for example, matches a global story of platform competition. Apple and Google are currently the dominant OS providers, but the likes of Microsoft and BlackBerry had their chance in the early days of the industry.

There is also a sense that competition may be better for R&D than cooperation. The decoupling of technical platforms for intellectual property (IP) protection and national security reasons could actually stimulate innovation and choice around the world, an outlook supported by clear precedent in the bipolar decades of the 20th century. But in business terms, this scenario also entails restriction of international supply chains and reduced economies of scale, which could be felt most acutely in Asia.

Stewart Paterson, a research fellow at the Hinrich Foundation, says investors that prioritize IP security may benefit from a separation of standards from an R&D standpoint but are likely to suffer commercially due to a reduced addressable market. At the same time, the fragmenting of the global marketplace will curb rising corporate profitability and aggressive monetary policies that support exit options. Nowhere will this effect be more acute than in the emerging industries that are set to inherit leadership of the global economy.

"Technology is at the cutting edge of the decoupling process, and that bifurcation is here to stay," says Paterson. "In Asia, countries are going to be put on the spot because it will be difficult for them to have access to both standards, and eventually, they will probably come down on the US side. Some of them might try to form a new economic bloc so they don't have to completely take sides, but at the end of the day, Asia ex-China will continue to be highly dependent on the US. This risks isolating China's industrial complex in Asia, which is the last thing they want with the Belt & Road initiative."

Capital questions

As cross-border money flows tighten, the most vulnerable companies will be those most dependent on foreign capital, including growth-stage start-ups. While this effect will be felt on both sides of the divide, it appears likely to be a bigger problem in China given the imbalance in investment flows to date.

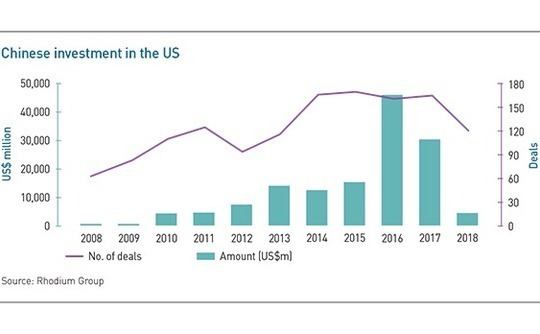

In the US, a precipitous drop-off in Chinese investment is underway, but the numbers are not alarming in the context of a $19 trillion economy. Chinese investment in the country peaked at $46 billion in 2016 before collapsing to a seven-year low of $4.8 billion, according to Rhodium Group. For China, the stakes are higher. Hong Kong-based economist Michael Enright estimates that up to one-third of China's GDP came from foreign-funded companies during 2009-2013.

Concerns around exit channels have simmered uneasily against this backdrop, with some US legislators calling for a ban on Chinese companies listing on local stock exchanges despite resistance to the idea from the likes of NASDAQ. Meanwhile, Chinese venture investors looking to raise US dollar funds are already said to be facing headwinds related to decoupling. So far, the jitters do not appear to be turning away institutions that have already profited from Asian growth, but it could be slowing down new entrants to the region.

"LPs that have never invested in China or Asia in the past are definitely going to have concerns because their impressions are based on what they read in the newspapers," says Chuan Thor, founder of AlphaX Partners and previously head of China at US-based Highland Capital Partners. "They're concerned about the macro and the ability for tech companies in China to go global. But more experienced global investors know that you can win regional markets where there are competing technical systems by making a product that becomes the de-facto standard."

Coolheaded approaches to decoupling are largely reinforced by confidence that Chinese domestic consumption is large enough to support significant success stories in relative isolation, as well as skepticism that an utter separation of technological ecosystems is feasible. Still, there appears to be a growing sense of resignation among industry stakeholders that at least some areas of high-tech cooperation will be disintegrated. The question remains, which areas and to what extent?

Clarity on these points will come slowly, in part because reliable parameters will only become evident after a period of case-by-case reviews. To date, this process is mostly reflected by the piecemeal decision-making of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). As one industry participant puts it: "CFIUS is like a diver coming up on a piece of plankton in the ocean and saying, this doesn't look right, we need to do something about this piece of plankton."

A lack of clarity is also inherent to the emerging nature of the technologies themselves, which sometimes results in seemingly innocuous businesses being roped off as data security risks. For example, some of the most recent US-based companies to trigger CFIUS blocks on Chinese investment include PatientsLikeMe, a health-tech provider, and Grindr, a dating app. Bureaucracy around these matters was further thickened last year with passage of the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), which extends CFIUS jurisdiction to minority investments.

A more direct indicator of how far decoupling will go could come to light within the year, however, as the Department of Commerce nails down its definition for "emerging" tech. This is still a vague status, effectively recognized as a more sensitive subset of "critical" tech, the existing mandate of CFIUS. A shortlist of 14 categories is now being evaluated for the emerging tech label, including AI, data analytics, 3D printing, digital surveillance, biotech, and brain-computer interfaces. Blockchain is not singled out, although there is a catch-all entry for "advanced computing technology."

This ambiguity offers a reminder that establishment of an emerging tech definition will probably do little to ease investor concerns around the unpredictability of commercialization within the relevant fields. Even if exacting and business-friendly specifications are announced, those tightly defined areas of restriction may go on to encompass large areas of business and investment activity as the technologies mature. Furthermore, CFIUS will continue to have a high degree of latitude when interpreting the Commerce Department's eventual decision, which does not bode well for China in particular.

"We will probably see a greater insistence upon mitigation remedies, and although the extent of those remedies will depend on the facts of each transaction, we can expect that the contours of the mitigation required by CFIUS increasingly will focus on the jurisdiction of the non-US investor," says Joseph Falcone, a partner at Herbert Smith Freehills. "Investors in countries classified as allies and partners will see various levels of mitigation. But for those in countries that, under anticipated regulations, may present special concerns, we're potentially looking at ringfencing the emerging technology element through divestiture as a precondition."

People movement

Rising tensions between China and the US have added another variable to this equation in recent months by increasing regulators' focus on blocking talent in addition to investment. When FIRRMA was enacted in August last year, its sister legislation, the Export Reform Control Act, was widely seen as a sideshow. Now the rule, which covers "deemed" exports such as foreign employees, is held up as a sign that things have gone too far, with sensitive US tech companies said to be under increasing pressure to avoid hiring Chinese engineers.

Here, the preferred modus operandi includes cumbersome licensing processes for foreign staff and layers of tech access approvals, rather than direct employment denials. Falcone adds that his firm is seeing increased interest regarding whether proposed cross-border acquisitions may implicate the US export control process even if CFIUS is not triggered.

"While CFIUS' role is more reactive in the sense that it is limited to reviewing potential acquisitions of US businesses by non-US persons, the US export control regulations are more affirmative about restricting the export of technology to certain foreign persons," he says. "Given recent export control reforms in the US, I expect we will continue to see significant and headline-grabbing activity in that process. Ultimately, I don't think this will be an insurmountable hurdle in all cases, but we don't yet know how these regulations will be put in place or how they'll be implemented."

Employee licensing restrictions are arguably the clearest proof that the decoupling of US and Chinese tech ecosystems could be on a truly irreversible course. That's because it freezes cooperation not just at an R&D or financial level, but at a cultural level as well. Hints that this trend is reaching deeper into the talent supply chain began last year, when the US State Department announced it would curb visa rights for Chinese technology students. If the trend continues, the gray area between national security and business regulation set to define decoupling boundaries in the future could also become a void of entrepreneurialism.

"The money deterred so far may be modest in comparison to overall foreign investment, but the problem is more than economic ¬– it has broader implications for the development of US technology," says Stephen Heifetz, a former CFIUS official and current partner at Wilson Sonsini, who represents the National Venture Capital Association in CFIUS reform talks. "Improving the situation will be challenging. The rules are rife with ambiguity, not just at the margins but at the core. I think that uncertainty may continue, even after new rules are implemented."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.