In scope: Asian fund managers and Cayman

Asian private equity firms may start moving their fund management entities away from the Cayman Islands due to new economic substance requirements. Is Hong Kong ready to accept them?

Processing a licensing application filed with Hong Kong Securities & Futures Commission (SFC) is said to take between six and 12 months: six for a flawless procedure in which all the paperwork is in order and the manager is beyond reproach; and 12 as standard. If the 150-plus private equity firms in the territory that are currently unlicensed simultaneously put in applications, some might spend years in limbo with no legal mandate to do business.

"I expect there would be a three-year push to get licensed, which might be a long wait to qualify for the benefits," says Jayesh Peswani, a Hong Kong-based director for relationship management at fund administrator Alter Domus. "Should the rush transpire, I would hope some sort of accelerated registration scheme would be put in place."

A clearer licensing regime has been a fixture on the wish lists of local industry practitioners for several years. Hong Kong is moving towards a system under which the entire fund management and investment process can be brought onshore. Legislation introduced in March enables PE firms to operate in Hong Kong without fear of receiving a tax bill. A local limited partnership ordinance is in development so funds can domicile in the territory. It would help if the managers could be properly regulated as well.

This was supposed to be a gradual process, but events on the other side of the world might be about to thrust it into fast forward. Nearly all PE firms active in Hong Kong, from pan-regional GPs to small-cap China players, locate their fund and their fund management entity in the Cayman Islands. This tried and tested formula is now under threat. Planned regulatory reforms will require fund management entities to demonstrate economic substance: either they accumulate local resources capable of running a fund or they relocate elsewhere.

Nothing has been finalized but the guidelines suggest private equity firms in Asia may have to rethink the structures that underpin their business – and do so by the end of the year. For Hong Kong to accommodate a potential wave of newly homeless fund management entities, there must be a workable method of licensing them. It is a concern not only for the two-thirds of the Hong Kong Private Equity & Venture Capital Association's (HKVCA) 240 GP members that are not licensed, but also for managers just finding their feet in the industry who want a watertight structure.

"There will be clients that say, ‘If we set it up now and we have to restructure in a few months, why go to Cayman?' Others will continue to want to use a Cayman manager," says Robert Searle, a partner with Campbells, an offshore law firm with a presence in Cayman and the British Virgin Islands (BVI). "Many are waiting to hear more, and we are telling them that things are in a high state of flux."

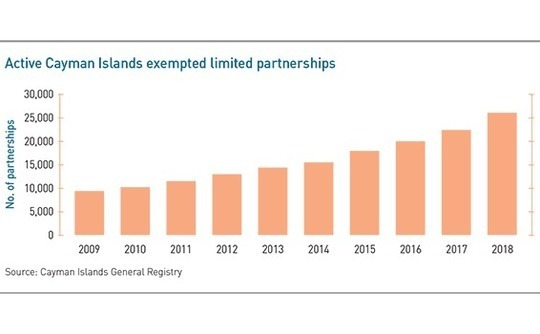

Another offshore lawyer based in Hong Kong observes that new clients are divided more or less straight down the line. Half are saying there is too much uncertainty and they don't want to go down the Cayman track. The other half believe the volume of business at stake – there were more than 26,000 active exempted limited partnerships in Cayman at the end of last year – means a commercial solution will be found. Most of those setting up new structures are China-based managers.

The BEPS effect

The starting point for this regulatory change was the BEPS initiative, conceived by the Organization for Economic Cooperation & Development (OECD) to stop investors exploiting gaps in the tax system to artificially shift profits to low or no-tax jurisdictions. Last year, the OECD and the EU turned their attention to UK crown dependencies and overseas territories, resulting in a string of economic substance legislation. The aim is to ensure that "relevant entities" have people and premises to support local business activity and are not simply locating in these jurisdictions for tax reasons.

Cayman's legislation came into force on January 1 and the deadline for satisfying an economic substance test is July 1. Annual reporting obligations will begin in 2020. The initial guidance indicated fund management entities without Cayman licenses – i.e. most of them – would be excluded from the legislation, as it the case for funds and investment entities. The regulator subsequently said all managers must comply with the rules. Fund management entities retain their place among the carve-outs in BVI's draft economic substance law, but this is unlikely to last.

"We are not known for funds, so there wasn't much focus on it; the focus was more on business companies," says Sherri Ortiz, a director at BVI House Asia, the territory's representative office in Asia. "We are on the gray list, not the white list, because the EU has asked for another review of our regulation and legislation, they don't fully understand our investment services. Ultimately, I think we will be required to capture fund managers."

Industry participants accept there is little chance of Cayman rolling back its stance on fund management entities. The best they can hope for is a substance test that isn't demanding to the point of being unworkable. Another guidance note is expected in the coming weeks, which may provide greater clarity as to what minimum level of substance looks like.

As it stands, a relevant entity must conduct its core income-generating activities in Cayman and, based on the size of that income, have an adequate amount of operating expenditure, office space and suitably qualified personnel in the jurisdiction. Core income-generating activities include taking investment decisions and preparing financial reports. It is unclear what constitutes adequate, but there is general agreement that hiring a retired executive in Cayman to sign off paperwork won't be enough.

"The core function of the manager will be to review investment recommendations put to them. You may need to demonstrate you have people in Cayman with the requisite skills and experience and authority to be reviewing those recommendations and making those decisions. That would be very difficult to achieve," says Darren Bowdern, a partner in KPMG's Hong Kong tax practice.

He adds that Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man have already published detailed criteria for substance tests, which might be used by the EU as a reference point when assessing Cayman. For example, the regulations require regular board meetings in the Channel Islands, with a quorum of directors – each of whom must have the knowledge and expertise to discharge their duties – physically present in the room. The minutes, which are kept in the Channel Islands, must reflect strategic decision making.

Weighing the options

The uncertainty regarding Cayman has left some private equity players frustrated. Several sources claim the offshore law firms are "fudging it" by underplaying the gravity of the situation and neglecting to give clients straight answers while furiously lobbying the Cayman government behind the scenes for a viable solution. The lawyers, for their part, say it would be unwise to try to give definitive advice because the dynamics are subject to change.

As is often the case, a GP must choose an approach that fits its risk profile. "I was advised, in the private equity firm I worked for, that if you hold four board meetings a year in the offshore jurisdiction, with the majority of directors from that jurisdiction, then you are pretty ironclad. If you decide you want to do it by telephone call and signed board meetings, with no physical presence or Hong Kong-based directors attending, your risk goes up, but you might get away with it," says John Levack, chairman of HKVCA's technical committee. "The more you do that's real, the safer you are."

For larger firms, there is an added reputational risk of being accused of window dressing. They are also among the relatively few for whom establishing real substance in Cayman could make sense because the scale of their operations means they are willing to bear the cost. Alternatively, they might be tax resident in another jurisdiction, so the compliance requirements do not apply. Smaller players, on the other hand, face a very different reality.

Taking on additional headcount and hiring out office space in Cayman could represent a substantial financial burden, while the prospect of flying in from Hong Kong several times a year for board meetings – a 24-hour journey with stops in San Francisco and Chicago – is unappetizing and potentially insufficient from a compliance perspective. Outsourcing to local service providers is another option and the legislation endorses this approach, provided they can perform the necessary duties. These third parties are forbidden from using a single employee to service two different clients at precisely the same time.

Even if the infrastructure can be put in place, Asia-based private equity firms might not be willing or able to wait that long. If they decide to relocate the management entity to a jurisdiction where they can easily claim substance, there tend to be only two realistic options: Hong Kong and Singapore. Neither is perfect. In Singapore, substance comes at a cost, with minimum annual capital expenditure for onshore and offshore managed funds. Hong Kong's challenge is catching up with its neighbor's product offering.

One issue is taxation. While the fund itself would be exempt, bringing the management entity from Cayman to Hong Kong could have implications for the treatment of fees. "Management fees and carried interest are typically booked into offshore entities that are not subject to tax in Hong Kong and then you have a transfer pricing payment back into Hong Kong. If you can't have those entities in Cayman or other tax neutral locations, questions will be asked as to where those amounts get booked and where they get taxed," says Adam Williams, a partner in EY's financial services tax practice.

As for licensing, the concern is that a private equity firm moving its fund management entity from Cayman to Hong Kong might simply decamp to Singapore instead if there is a long backlog in applications. Singapore is said to be encouraging the formation of platforms whereby a responsible officer oversees a manager's activities while an application is in process. It is suggested that Hong Kong adopt a similar approach or simply grant temporary waivers to well-established firms. The SFC naturally fears letting in bad actors and having to spend the next two years firefighting.

An additional complication is that many private equity firms don't fully understand which licenses they need. There are three areas relevant to alternative asset managers: dealing in securities (type one), advising on securities (type four), and asset management (type nine).

"In recent years, a lot of mainland Chinese managers have come to Hong Kong and they aren't familiar with the licensing and regulatory regime," says Lorna Chen, a partner and head of Greater China at Shearman & Sterling. "If you don't have type one, you can't execute deals or even arrange conference calls with targets to get deals done. Without type four, you can't write reports to your investment committee. And if you want to put the investment committee in Hong Kong, you really need type nine."

The minimum paid-up share capital for a type one license is HK$10 million ($1.3 million) if a manager is engaging in certain kinds of activities, twice the amount required for the other two licenses. As a result, some managers are looking to conserve costs and applying just for type nine, assuming it will cover all their activities. However, the SFC has been reluctant to issue these licenses because it believes some element of discretionary management should be involved, whereas most managers are merely advising the offshore fund on investment decisions.

The new normal?

The SFC will ultimately have to offer more guidance, but developments in Cayman may require action sooner rather than later. "We have been arguing for five years that it makes sense to have more operations in Hong Kong, where the real people and the substance are. We have also said there is likely to be a lot of inertia because Cayman works well, and it will take years for Hong Kong to build momentum," says HKVCA's Levack. "If Cayman must increase its economic substance requirements for managers, the option of re-domiciling the manager in Hong Kong could be a nearer-term solution."

It is important to note that economic substance legislation does not impact the fund, which means Cayman retains its attractiveness as a domicile. Given LPs are comfortable with this arrangement there is no desire for change – managers want to spend pitch meetings preaching the virtues of their investment strategy, not the virtues of Singapore over Cayman. However, some industry participants in Hong Kong argue that the economic substance debate could give impetus to a longer-term shift in mindset, resulting in fund and fund management entity being aligned in a single jurisdiction.

"I think more people will base their managers where they have their operations in the long run, whether that's Singapore, Hong Kong, mainland China, or Tokyo. Concessions will allow them to establish substance and in turn access to underlying platforms," says Peswani of Alter Domus. "The fund can stay domiciled in Cayman but that could start to defeat the purpose. If you have an onshore manager and an offshore fund, the incentives over time would be reduced because you might not get the full benefits from your onshore operating jurisdiction."

SIDEBAR: Holding patterns - The BVI

The British Virgin Islands (BVI) business company is said to be the world's most popular international legal entity. While the Cayman Islands is the go-to fund domicile, BVI had over 400,000 registered corporate entities as of December 2018, four times as many as its Caribbean neighbor.

Business companies are not immune to the global drive to curb harmful tax practices, with BVI introducing its own economic substance legislation at the start of the year. However, draft guidelines indicate that business companies – used by PE firms for all kinds of investment holding structures below the fund level – will only be affected if they perform certain business activities.

"You are compliant just by having a registered agent, which you must have anyway, and having a registered office, which can be met by the registered agent's office," says Sherri Ortiz, a director of BVI House Asia, the territory's representative office in Asia. "There is an additional requirement for a BVI resident director, but that is normally provided by the registered agent. Within the registered agent relationship, all substance requirements can be met."

A pure equity holding company – which only holds equity interests in other businesses, receiving dividends and capital gains – is subject to an economic substance test, although it is not as rigorous as for other entities. Compliance involves having adequate human resources and premises in BVI. Local industry practitioners recommend placing debt alongside equity in the structure if there is a desire to avoid the pure equity designation.

BVI's product offering is built on flexibility and low cost. Ortiz notes that the legislation is broad with a view to preserving this flexibility. She adds that any investors who fear moving in scope have plenty of time to adapt to the new conditions. Annual reporting obligations do not begin until 2020 and she estimates it will take the tax authority two years to become fully attuned to the process and start making specific inquiries.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.