China tech valuations: Unnatural acts

China’s tech sector is gripped by uncertainty, but some GPs will do anything to avoid marking down their portfolios. LPs are entitled to ask whether unicorns are still worthy of a billion-dollar valuation

Taking the temperature of China's technology sector has a literal application. If start-ups are reluctant to turn on the air conditioning in their offices as the summer months approach, all is not well.

Cost-cutting is increasingly visible among larger players in the space, with the likes of Tencent Holdings making job cuts. Lower down the food chain, behavior is even more desperate. Companies have been known to go into hibernation, minimizing electricity consumption and operating with a skeleton staff, to ride out periods of economic difficulty.

This doesn't mean business models are unviable, but founders and investors are reluctant to raise new capital at lower valuations than before. The perception is that making a public admission of weakness in a competitive market could damage future efforts to attract capital on favorable terms. Flat rounds, debt financing, freezing product development, turning off the lights – anything but a down round.

"My experience of Chinese entrepreneurs is they will perform unnatural acts to avoid reducing their valuations. They resist far more than their counterparts in the US," says Gary Rieschel, a co-founder of China-based Qiming Venture Partners. "China hasn't gone through a significant downturn where capital dried up, but it isn't going to escape the inevitable cycles that every other VC market has gone through, especially with the scale it is at now."

Off the boil

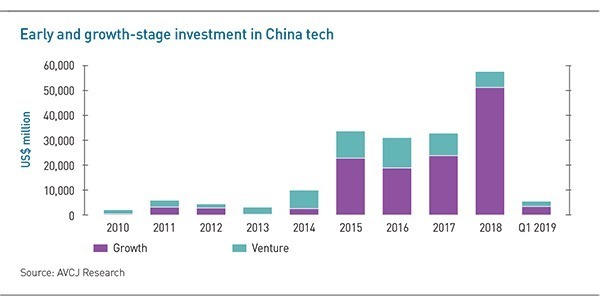

Around $155 billion has entered early and growth-stage technology deals in China over the past four years, more than six times the total for the preceding four years. Half the capital committed since 2015 has gone into 40 or so mega rounds of $500 million and above. But the music slowed towards the end of 2018 as weakening consumer sentiment and declining public markets spooked investors. A pullback in renminbi-denominated fundraising also reduced the amount of capital available.

For institutional investors awaiting fourth-quarter reports from portfolio GPs, the question was whether valuations would reflect the chaos they were reading about. Once a position is liquid – and plenty of late-stage investors are now underwater on companies that went public in 2018 – it is hard to argue against a mark-to-market valuation. Businesses still under private ownership are a different matter: an LP in two funds that are invested in the same start-up could receive different valuations.

"When you are doing a mark to market for a venture capital investment it is much more an art rather than a science," says Wen Tan, co-head of Asian private equity at Aberdeen Standard Investments. "Many of these companies are pre-profit, so how do you go about thinking what is a mark to market? And whatever principles you apply, it's a much broader range of outcomes, given the fuzziness of the methodologies."

Valuation discrepancies are a global issue in venture capital. Jessica Archibald, a managing director at US-based fund-of-funds Top Tier Capital Partners admits that the system is subjective and therefore unreliable. Her firm is often exposed to a single company through three or four different channels and the valuation spread can reach 30%. This is not always the fault of the GP. Staff in the New York office of an accounting firm might offer different guidance to their colleagues in San Francisco.

China presents an additional challenge because the GP community is younger and the ecosystem more volatile. On one hand, various sources insist there is widespread denial among investors, with positions still carried at unsustainable valuations. On the other, investors claim their assessments are based on strong fundamentals and clear competitive advantages, at the industry and company level, respectively. Who should an LP believe?

Certain VC firms are known for taking a highly ascetic approach to valuations. Kleiner Perkins is among the most disciplined outfits, with several investors saying that positions are often held at cost – or close to it – until realization. When a restructuring opportunity came up a couple of years ago involving one of the funds raised by the firm's China affiliate, the portfolio is said to have been priced conservatively enough that investors would have paid a premium to the net asset value. Unicorns ranging from CreditEase to Ximalaya were not marked at levels that reflected their true worth.

James Huang, a managing partner at KPCB China, believes this reputation is the product of a rigid focus on early-stage investments and deep roots in US venture capital. The further a firm gravitates from these spheres of influence, the less disciplined they may become.

"Once funds get to $1-2 billion, it's hard to say they are really venture, and when they have a lot of money, they become less sensitive to valuations," says Huang, who launched healthcare-focused Panacea Venture in 2017. "There is also a difference between Chinese firms that originated in the US and those that did not. If your LPs are US-based, the accounting is done to US standards and approaches to mark-ups and mark-downs are consistent. Homegrown GPs don't do their accounting like that."

Doing the math

The simplest way to value a company is based on the previous funding round, but even that can be more complicated than it seems. Some investors mark up the value of a company as soon as they receive the term sheet for a new round, while others wait until the round closes. If these two events fall either side of the quarterly cut-off point, an LP could receive different numbers from two GPs.

Discretion can also be exercised when considering the wider context of a funding round. A corporate come in at an elevated valuation for strategic reasons, so the price does not tally with what a financial investor would pay. Similarly, a GP that is desperate to get exposure to a company could pay up for access, but it's a one-off and the round represents a small percentage of the enterprise value. In either situation, existing investors may ignore the mark-up and stick to what they have.

For unicorns, an illiquidity discount is somtimes employed. A venture capital firm would automatically cut 20-30% off the valuation of all privately-held start-ups worth $1 billion or more – essentially an acknowledgement that the business is now so big, it would take time to liquidate the position, and much like a public company, prices may fluctuate in the interim.

The longer the lag period to the most recent funding round, the harder it is to justify holding an investment at that valuation, although many still do. Experienced GPs tend to use the last round as the starting point and then make additional assessments of a company's performance against the plan and where comparable publicly-listed businesses are trading.

Qiming, for example, was one of the first institutional investors in Xiaomi, backing a Series A for the mobile phone maker at a valuation of $40 million in 2010. As the funding rounds progressed, Xiaomi climbed from $165 million to $1 billion to $10 billion to $45 billion in late 2014. But then equity funding ceased, and performance dipped as rising local competition and poorly executed international expansion plans ate into sales.

"We took down the valuation from $45 billion to $30 billion for illiquidity and then there was an adjustment during that three-year period when they were working through competitive issues and getting back on a growth trajectory," says Rieschel. "It's an imprecise science, but we did the same with Meituan-Dianping and I think we would definitely take a liquidity discount on ByteDance [currently valued at $80 billion] if it didn't raise money for the next two years."

Xiaomi went public in mid-2018 and Meituan-Dianping followed a few months later, each achieving a market capitalization in excess of $50 billion. They are now trading below their IPO prices and the public valuations are less than those for the most recent private funding rounds. This is of little concern to Qiming, which went in early, but the venture capital firm has struggled with other deals.

Online clothing retailer Vancl was poised for a US listing in 2012 until an expansion strategy intended to build up market share went painfully wrong. Qiming marked down the asset within six months of deciding that all was not well, but Rieschel claims that other investors were still holding the company at an approximately $3 billion valuation two years after a Series F round in 2011. The GP later wrote down the position even further, having concluded that Vancl would need to be recapped, and received calls from LPs asking why there was an 80% discrepancy in valuations across the shareholder register.

The company was recapped in 2014 and has effectively been written off by most investors that have exposure to it. Qiming's willingness to accept the reality before its peers can be tied to the fact that it was the only one to take money off the table when the going was still good. Investors with a lot to lose might be incentivized to delay the moment of reckoning, and in the absence of a standardized approach to valuations, they have the scope to do that.

"Some GPs stick with the latest private round, saying based on all these other ways of evaluating the company, we believe this is the right valuation," says Weichou Su, a partner and head of Asia at StepStone Group. "There are always reasons not to mark something down. There is never an exact listed comparable. You take 10 similar companies, construct a benchmark, and use that to derive a valuation, but there will be some companies you choose not to include in the benchmark."

Down and dirty

Top Tier analyzed all the M&A transactions within its portfolio over the 18 months ended December 2018 and found there was an average 2x increase in valuation between where managers were holding positions in the quarter before acquisition and the acquisition price itself. This suggests that conservatism prevails – but there are two caveats. First, 80% of Top Tier's activity is in the US. Second, given China's M&A market is less mature than that of the US, the bulk of VC exits still come via IPO and volatility can play havoc with timing.

If a portfolio company requires additional capital, but an investor is reluctant to countenance a down round at a lower valuation, perhaps because it is about to launch a new fund, there are various options. The classic approach is to use a "dirty term sheet," where the valuation is slightly up, but conditions are attached that can complicate future financing if performance targets are not reached.

According to Thomas Chou, a partner with Morrison & Foerster, anti-dilution provisions are becoming more common in late-stage China deals. These serve to compensate an investor – through the issuance of additional shares, usually by converting preferred shares to common stock at a higher ratio – when a funding round takes place at a lower valuation than an earlier one in which it participated. A similar mechanism is employed to protect investors when an IPO price falls short of the previous private round.

It falls on the founder to bear the brunt of the dilution. The same applies to liquidation preferences. Later-stage investors might come in on the proviso that they get paid out first in the event of an M&A exit, pushing founders so far down the preference stack that they might not see any money at all if the company valuation has declined. In certain instances, they are offered separate performance-based incentives to carry on managing the business.

"It is often hard for GPs to do down rounds, you can have problems around issues such as anti-dilution. We are seeing a lot of flat rounds or slight mark-ups," says Chuan Thor, founder of AlphaX Partners and previously China head at US-based Highland Capital Partners. "When we do valuations, we aren't just looking at the multiple from the most recent round. We also look at the terms and what that means for different exit scenarios. For instance, what happens to the ownership stakes if one investor from the previous round has a 1.5x liquidation preference?"

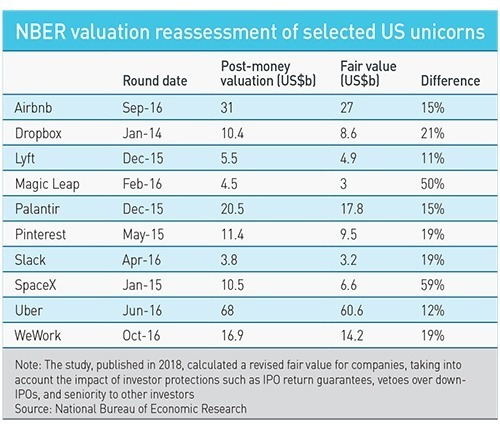

A study published last year by the National Bureau of Economic Research sought to remove the valuation inflation effect of investor protections such as anti-dilution ratchets, vetoes over down-IPOs, and liquidation preferences. The authors assessed 135 US-based start-ups valued at $1 billion or more and found that 65 did not warrant unicorn status. These companies were on average 50% overvalued.

Attempts to game the system in China extend to raising tiny rounds from brand name investors purely to justify a valuation. Huang of KPCB claims to have received countless calls from financial advisors asking for contributions as small as $10,000 at astronomical valuations. This allows a GP to string out the narrative to LPs a bit longer, but it does not address a company's capital needs. One way to achieve both goals, while avoiding the draconian provisions of a flat round, is to issue debt instead of equity.

Xiaomi obtained debt financing during its difficult years, but by then it was generating $12 billion in annual revenue and turning a profit. For companies that don't have sustainable cash flow, such a course of action can be dangerous. "I am talking about businesses that are giving away 75 cents for every dollar they are borrowing. Imagine if you had tried to jam debt into the structure at Mobike or Ofo, it wouldn't make sense," one VC manager observes. He then stops and corrects himself, noting that this is exactly what China's beleaguered bike-sharing companies did.

Mobike and Ofo are hardly examples of sound financial management; the former is now a drag on Meituan-Dianping's balance sheet, and the latter is teetering on the brink of insolvency. Nevertheless, other start-ups have been quick to embrace the debt option. These products typically automatically convert to equity at a deep discount to the next round, if additional equity funding is forthcoming, or to the previous round. These are down rounds in all but name.

"You are kicking the can down the road a little bit, but everybody knows that achieving the last round valuation is almost an impossibility," says James Lu, a partner at Cooley, who is currently working on several such deals. "Valuations in some companies in China went up so quickly and down so quickly that people can get shell-shocked. Founders and early investors in some of those cases are trying to keep companies alive in the hope of a turnaround. The risk is that later-stage investors, because they have lost so much money, just write it off."

With companies staying private for longer and raising ever larger rounds that feature a wider variety of investors – based on check size, risk appetite, minimum required return – these conflicting priorities are accentuated. Negotiations can be fraught. Whereas for an expansion round the lead investor's counsel tends to represent all the investors, everyone brings their own lawyer to a board meeting for which the main agenda item is a whether the company lives or dies.

One advisor recalls spending seven months locked in talks with five investors that were arguing over who should contribute how much, and on what terms, to a $10 million capital injection. Two of the five had committed nearly $200 million between them to the company's previous round. But the differing levels of exposure within the shareholder group became an impediment as they tried to find a solution that worked for everyone.

Long-term credibility

It is incumbent on the LPs to analyze the numbers submitted to them and establish whether there is more to valuations than meets the eye. Many GPs pass the same performance information to consultants that create benchmarks, and it is usually taken on trust.

Vish Ramaswami, a managing director with Cambridge Associates, notes that movements in public markets are largely responsible for quarterly fluctuations and these positions are relatively easy to track. As for outliers based on private marks, once identified it usually takes about a week to assess whether the numbers are credible.

Moreover, experienced investors should be able to see through any artfulness. "If it's three VC funds with 200 positions, it's hard to go through every single one. But you look at the largest investments. You identify the positions that are over a year old and haven't been marked up or down, and that's an amber flag. If there are too many of them and there's no good explanation, the LP digs into that. Maybe they get comfortable with it, or maybe it's a pattern and that's a red flag," says Ramaswami.

A minority of GPs engage accounting firms and investors regarding valuations on a regular basis. AlphaX claims to consult informally with its accountant every quarter – the official audit happens once a year – to ensure it is adhering to protocols. Others ask their LP advisory (LPAC) boards to approve valuations. At the very least, LPAC meetings should be forums in which these issues can be addressed as and when necessary, but much rests on the quality of the LP base.

"There are concerns when a lot of money comes into venture capital from people who might not understand these nuances," says Archibald of Top Tier. "A fund might be playing games with valuations or it isn't forthcoming with information, and the investors don't know what questions to ask."

Ultimately, there is nowhere to hide. All private equity and venture capital firms are judged on how much money they return to investors. While hiding the truth from LPs might make it easier to raise the next fund, building a sustainable franchise across multiple vintages becomes harder if a manager cannot shake off a reputation for playing fast and loose with valuations. Undervaluing and overdelivering – or offering predictable outcomes rather than unpleasant surprises – is the preferred course of action.

"Managers who understand this is a long game and want credibility among LPs are more inclined to be conservative on the marks because they know they will be crucified they end up selling an asset below the carrying value. LPs have long memories about those instances," says Edward Grefenstette, president and CIO of The Dietrich Foundation, which has significant VC exposure in China.

For many investors, studying the implementation of valuation methodology is a key part of ongoing due diligence. Watch for long enough and the same trends will play out time and again. In 2011, China was gripped by group-buying fervor, enabling market leader Lashou to raise $166 million and file for an IPO in the space of 12 months. By the middle of 2012, the wheels had fallen off. Grefenstette questioned a GP's carrying valuation for Lashou amid the furor and the unsatisfactory response contributed to his decision not to re-up. Similar questions have probably since been asked of investors about peer-to-peer lending and bike-sharing.

"Every time we run into a situation that requires judgment from the GP, that gives us more data, more insight into how the people think," Grefenstette adds.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.