Asia's lower-tier cities: New horizons

PE and VC players are slowly discovering the investment and business expansion opportunities in the lower-tier cities of developing Asia. Risk-reward calculations are becoming more complex in the process

For many consumer sector investors, Chengdu is the quintessence of China's economic boom, the opportunity in cities below the top tier, and the notion that the frontiers of modernization are constantly receding into less familiar parts of the map. In the past 20 years, the population of Sichuan's capital has doubled to 10 million, but that's still only a fraction of the 80 million consumers in the rest of the province, about half of whom are clustered in relatively anonymous Singapore-sized cities.

China-focused mid-market buyout firm Lunar has played in this sub-region since 2012, when it acquired babywear maker Yeehoo. The company had three locations in Chengdu at the time of investment, but now operates more than 30 stores across Sichuan. Importantly, the holding period has overlapped with massive e-commerce infrastructure investments from the likes of JD.com and Alibaba Group, which allows merchants to establish their own online stores.

Getting the right online-to-offline (O2O) mix is a delicate consideration when expanding a business in any rapidly digitizing market due to countless variables around existing brand exposure and consumer sophistication. But in China's lower-tier cities, at least two nuggets of O2O wisdom appear universal: intense engagement on social media is indispensable and piggy-backing on the infrastructure built by conglomerates is the only way to accumulate appreciable customer attention in the early stages.

"When first tapping into Sichuan, our strategy was to focus on Yeehoo's e-commerce presence with a limited number of offline stores because, in rural areas and lower-tier cities in China, physical retail is underdeveloped, and consumers are looking for virtual consumption as part of the shopping experience," explains Yi Li, a partner at Lunar. "After achieving scale and brand recognition online, we slowly expanded the number of offline stores. By doing that, we were able to penetrate the local market with efficient cost, and Yeehoo is now one of the top-three baby brands on [Alibaba's] Tmall."

Growth story

Although there are myriad metrics to illustrate the economic expansion in Asia's lower-tier cities and an equal diversity in the definitions of what constitutes "lower-tier" status in any given market, the essential trends are easily discerned from the available data.

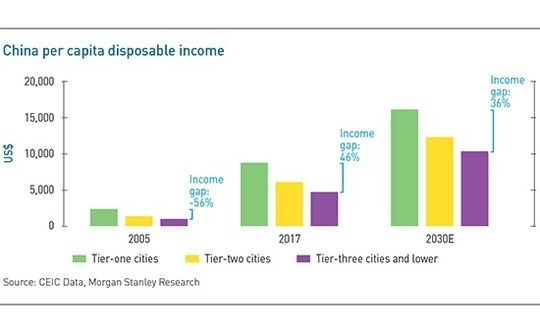

According to Morgan Stanley, for example, total household consumption in China's tier-three and lower cities is set to climb from $2.3 trillion in 2017 to $6.9 trillion by 2030. Disposable income levels in tier-one cities were 46% higher than the lower-tiers in 2017, but the gap is expected to tighten to only 36% by 2030. The speed and scale of this shift are unmatched and suggest that China may offer relatively easy access to new consumers, but challenges remain.

It is a pricing equivalence that would have been unthinkable only five years ago, and it has put significant pressure on international operators looking to expand their footprint outside big and small population centers alike. Even in segments with no clear domestic competitors, brand-powered hype has proven insufficient fuel for maintaining a hinterland empire. Victoria's Secret, which enjoyed a rabid welcome in 2017 upon the launch of its flagship store in Shanghai, confirmed this month it would close 53 outlets nationwide due to declining sales.

Premiumization themes in regional China are therefore often best played with a significant local flavor. Lunar has found that consumers in regional areas go local as they go premium, and it has responded in the beef jerky niche with investments in LifeFun and Niutou, favorites in Shanghai and Guizhou province, respectively. Whether a brand is celebrated in a large or small city, its connection with premium local tastes makes it more attractive than international names in many lower-tier markets.

Further upstream, branding is less of an issue, but China investors concur that the professional clout of a consumer industry supplier in one region will not necessarily translate into respect for company heritage when it moves into another part of the country. Likewise, the weaker skills base in a lower-tier city often offsets many inherent cost advantages such as cheaper real estate and leasing. Food and beverage (F&B) chains, in particular, have been known to flounder due to a lack of sufficiently competent accounting talent at lower-tier levels.

"For the most part, country heads here have absolutely no understanding of what's going on in these markets," says Ben Cavender, a principal at China Market Research. "What they hear is ‘good population base and growing GDP and consumer spending,' but they have very little granular understanding of the actual consumer and what they want. It comes down to what information source you trust. Do you go it alone, hire somebody, or rely on platforms like Alibaba? In many cases, they're offering a lot of consumer data, but the conclusions aren't necessarily relevant to what's going on in the market."

In recent months, the specter of a slowing economy has introduced yet another complication to the China equation, with consumers in lower-tier cities seen as likely to be more careful about prioritizing value for money. This will result in a continued pivot toward local products, but also a tendency to seek out brands online that have had their quality validated by a brick-and-mortar presence in larger cities. Increased domestic travel will amplify this effect because tourists returning home to the lower tiers will be more educated about the market.

The trend will not be missed in India, where the government is planning to build 100 new airports across the next 15 years, including 70 in locations that do not already have one. Airport retail has consequently become a significant part of local private equity strategies aimed at reducing the risk of lower-tier expansions. The idea is that the duty-free concessionaires strip out business costs by providing built-in management of inventory, staffing, and various infrastructural supports.

Lower-tier cities in India are not outpacing the tier-ones as quickly as in China. EY splits the country's 50 biggest cities into eight leading metros and 42 lower-tiers, charting per capital GDP growth rates of 8.3% and 8.9% for the two groups, respectively. But the consensus is that although the Indian boom is less dramatic, its opportunities are equally profound.

Nithya Easwaran, a managing director at Multiples Alternative Asset Management, refers to the phenomenon as "consumption creep." She estimates that the number of cities where more than 40% of households have an annual budget of at least INR1 million ($14,400) will grow from less than 10 currently to around 50 in the next decade. Multiples is betting on this progress with cinema chain PVR, which has grown from about 25 to 60 locations over the last six years.

Much of the PVR story is focused on going deeper in the lower-tiers. The company's latest push includes a likely new location in Kolhapur, a city with 600,000 people in the metro area and less than four million in the surrounding district. Multiples' plan banks on the fact that every town in India has at least one struggling independent cinema, which can partner with PVR through rental or revenue share agreements, allowing for multiscreen conversions and dining add-ons.

"It will not be as plush as what you see in the tier-ones, but that's okay because it will still be many notches above what that market has had as an option," says Easwaran. "You want to provide a value proposition in terms of the cost of the tickets and F&B, so PVR actually has a separate team looking into this, because it's very different from what they're doing in the tier-ones and tier-twos. If they can stabilize this model, they will do it initially in about four or five tier-three cities, and we're excited because once you get this right, you can scale it up significantly."

Domino's Pizza, with shops in more than 260 Indian towns, is perhaps the best example of how this can work in discount segments. But bigger-ticket items are increasingly defining the opportunity as well. Easwaran says Arvind Fashions, a Multiples company that markets pricier brands such as Calvin Klein, has been tracking 25-30% sales growth at its 35 tier-three locations. Still, the difficulty in tapping these markets may ultimately be less about disposable income and price point, and more about culture.

ChrysCapital Partners suggested as much with its investment in Hindustan Media, a newspaper publisher focused on the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh – well-populated areas but devoid of first-tier cities. The company wanted to start in the lower-tiers, catering to the highly localized social and language needs of smaller communities, while building brand recognition and avoiding the intense competition of the major metros in the vulnerable, early development stages.

This approach can be effective in a range of consumer segments because it acknowledges the value at the bottom of India's economic pyramid while also setting up improved access and negotiating positions with regional suppliers. This can in turn result in lower-tier companies gaining an advantage in supply chain economics versus their tier-one counterparts.

Sanjiv Kaul, a partner at ChrysCapital, notes, however, that such strategies require a sharper focus on the local nuances of people-product interaction. To this end, the GP helps companies in lower-tier cities access first-tier cities through staffing-related value-add measures while also providing local market education to tier-one companies that want to enter lower-tiers.

"If you want to be truly pan-Indian, you need to have a very different mindset because every 100 kilometers, the language, culture, dress code, and eating habits change dramatically," says Kaul. "That's why it's important to create a knowledge center within a private equity firm that can handle companies going from tier-ones to tier-twos and tier-threes, and vice versa. Companies going from the lower-tiers to the metros require a lot of training and help with recruitment."

Digital domains

Practical O2O considerations in India have closer parallels with China, especially with respect to the importance of working with one of the leading infrastructure providers. Amazon and Flipkart are must-have intermediaries for retailers looking to tap the increasingly mobile-connected lower-tiers, but investors will have to be vigilant about pricing control.

Products listed on India's main online aggregators are subject to extreme discounts, which can destabilize a brand. There is much talk of companies developing omni-channel marketplaces to ensure consistency, but widespread adoption of this approach in the lower-tiers is said to be 10 years away. Solutions in the meantime are likely to include a greater emphasis on participating in brick-and-mortar multi-brand outlets, or MBOs.

The O2O story differs in Southeast Asia primarily because the region lacks an online hegemon. Expansion into lower-tier cities and rural areas appears to be the forte of regional new-economy heavyweights such as Grab and Go-Jek, which operate multi-sector online platforms in about 230 and 170 cities, respectively. But the fact that these are competing VC-backed ecosystems underlines the immaturity of the market and the headwinds around breaking businesses out of the largest cities.

"With the unicorns in Indonesia, there's still a battle for market share in e-commerce, so retailers don't have this one monolithic question about winning with Amazon or Alibaba," explains Usman Akhtar, a partner at Bain & Company. "That fragmentation makes it harder to use online sales as a way of reducing reliance on costly distributors in tier-three cities. Also, the strongest e-commerce players in Indonesia and Southeast Asia use C2C models, which creates even more fragmentation issues."

This view offers a reminder that lower-tier marketing hurdles pre-dating e-commerce – including infrastructure, logistics and distribution networking – remain the biggest challenges in Southeast Asian expansion. For the largest operators, in-house distribution businesses can service specific needs such as navigating the difficult geographies of the region's archipelagos or scaling complex cold chain supply lines. Most companies, however, will continue to rely on traditional distribution partners.

The distribution supply industry is robust but characterized by patchy differentiation in strengths and weaknesses, which may be felt most acutely in retail. Branded products, such as fast-moving consumer goods, often include perishable items or require higher standards around quality control. Stores selling the same items in outlying areas are known for charging higher prices than the main cities due to logistical costs related to these issues, which can, in turn, hamper lower-tier customer uptake. This has not changed with the dawn of online shopping.

"It's going to be a long time before a company cracks sales across Indonesia's tier-two and tier-three cities by relying entirely on e-commerce. You just can't do away without the traditional distribution partners getting your product into brick-and-mortar stores," Akhtar adds. "The market needs time, so for the next few years, there will still be a big package of questions to unpack about finding the right distribution model in both the general and modern trade."

Outside in

As home to almost all Southeast Asia's unicorns and a consumer market of some 260 million people, Indonesia is understandably the focus of much of the discussion on lower-tier expansion. Like all countries in the region, except Vietnam, it is dominated by one disproportionately large capital city. But the combination of the large population and island chain geography seems to encourage hubs such as Medan and Surabaya to absorb surrounding lower-tier cities into statistical areas of 5-6 million people.

As a result, Indonesia could be uniquely positioned for circumferential growth plays, where companies are started in the outlying areas and gradually move toward the tier-ones. Khailee Ng, a managing partner at 500 Startups, an investor in Grab, sees lower-tier cities in the country not only as potential expansion zones but also as innovation centers where locals hungry for technology and new opportunities are creating meaningful businesses with little more than a smart phone.

The potential is seen as especially ripe in places like Medan, where urban sprawl, upward social mobility, and technology penetration are creating a new kind of tier-two opportunity set. "As more of the country urbanizes, those cities will grow," Ng told AVCJ last year. "It's not day and night where you have metropolitan areas and then coconut trees – there is a big middle."

Nevertheless, the key to tapping Indonesia's rising disposable incomes in the big middle and beyond remains in consumer staples, not tech. Creador is stressing this point with breakfast cereal maker Simba, which has extended its products to some 250,000 outlets by partnering with Nabati Snack, a local food giant with substantial in-house distribution capacity.

Meanwhile, the firm's investment in Malaysia-based Mr DIY has helped the home improvement retailer grow at a pace of 100 new stores a year. The focus was initially on major population centers, but the biggest successes have been in the small towns. Interestingly, this process has highlighted some of Southeast Asia's greatest growing pains around scaling businesses, as well as unexpected similarities with the most developed markets globally.

"It mirrors what is happening in US where the towns are too small to support a Wal-Mart or one of the bigger chains, and the dollar stores continue to thrive," says Brahmal Vasudevan, CEO of Creador. "So it's a big area where we're looking at a number of new retail themes that play on this idea. But one of the things in smaller cities and less developed countries is that the organization of retail is very limited, which sometimes makes it quite challenging to find an appropriate space. There may be higher capital expenditures and lead times."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.