Japan VC: Positive energy

Japan’s quiet venture capital space is booming within its own borders. Signs of a stronger exit market and an exuberant influx of corporate involvement are encouraging themes, but they will play out slowly

When 500 Startups Japan reinvented itself as Coral Capital earlier this month, it said much about the venture capital firm's home ecosystem. The most poignant of these parallels might be the name change itself as the Japan VC space seeks to carve out its own identify in the shadow of Asia's larger and faster-growing markets.

Coral's break with its US moniker came with a fresh $45 million fund and a raft of new LPs. While the firm's debut vehicle closed in 2016 with backing from corporates and government entities, almost half the corpus of Fund II comes from institutional investors, including one of Japan's traditionally risk-wary pension funds. These commitments coincided with the sale of restaurant app Pocket Concierge to American Express in a rare strategic deal for the IPO-dominated exit market.

The firm has made three exits since inception in 2015, and all of them have been strategic acquisitions. The others went to domestic corporates, including Tokyo-listed Tsunagu Solutions, which picked up software and design specialist Regulus Technologies last year. Such milestones belie a steady sense of realism about a local penchant for conservatism, however, as well as the long timeframes that go with any transformation dependent on large bureaucracies.

"Institutional investors have realized there's an opportunity in Japanese venture, but probably 90% of the ones communicating regularly with VCs are so far just investigating," says Yohei Sawayama, a co-founder and managing partner at Coral. "Corporates are chasing start-ups more aggressively through investments, partnerships and acquisitions as they realize that innovating in-house is difficult. But that's still in the early stages too. Most corporates are struggling with how to do things like post-merger integration and compensating founders."

Laying foundations

Japan started seeing a real change in venture capital activity and cultural acceptance of entrepreneurship about five years ago, when the country's first generation of homegrown internet companies, including the likes of Rakuten, Line, and Gree, started spinning out serial founders and angels. Meanwhile, international players such as 500 Startups, WeWork, and Plug And Play began bringing significant seed-level resources and expertise to the market.

Increased interest from foreign incubators and accelerators coincided with the swapping of Japan's uniquely local technical standards for global platforms. Apple and Google now cover essentially 100% of the Japan smart phone market and Amazon infrastructure is ubiquitous in the online business sector.

A breakthrough moment came last year, when Japanese corporate cash reserves were said to hit a historic high of $890 billion and pressure to deploy piqued in the context of a loosely defined, government-sponsored movement known as "open innovation." This led to a flood of corporate venture capital activity, especially in early-stage investment and fundraising

The result to date has been an exacerbation of a later-stage funding gap and a sharp increase in early-stage valuations, with pre-revenue rounds said to have tripled in size to nearly US or China levels. Many freshly minted start-ups have queued up to IPO in 2020 in an attempt to leverage the global publicity expected to come with the Olympic Games in Tokyo. The country's smattering of longstanding independent VCs, including Infinity Ventures, are consequently biding their time.

"We've only backed a few Series A deals in the past 18 months because the valuations have been unreasonable," says Akio Tanaka, a co-founder and managing partner at Infinity. "A lot of companies that are raising early-stage capital now will face more scrutiny when they go back to the market in the next couple of years, and a valuation adjustment might happen. I think after the 2020 peak, everyone will say the party's over, let's get back to reality."

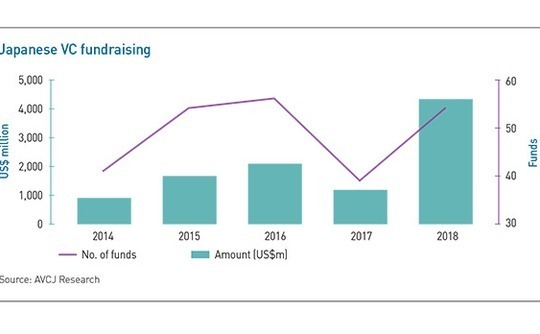

The impact of the corporate venture boom on Japan's small VC space has been enormous. According to AVCJ Research, VC fundraising in the country hit $4.3 billion in 2018, roughly equal to the three prior years combined. Some of the higher profile entrants in recent months include Japan Airlines, with a $70 million fund, Salesforce Japan, with a $100 million fund, and NTT Docomo, an existing VC investor returning with a new $500 million vehicle.

About half of total venture investment is now said to come from corporate VC units. Investment rounds that included exclusively Japan-based funds amounted to $1.3 billion and $1.1 billion in 2018 and 2017, respectively. This compares to a range of $645-900 million during the three prior years. Despite the pressure this phenomenon has put on the industry's financial dynamics, optimism persists that it brings a new technical depth to the ecosystem.

"Valuations in the early stages have risen due to increasing competition from corporate venture capital, but that's good for entrepreneurs in deep tech like artificial intelligence or the internet-of-things," says Shinichiro Hori, CEO at YJ Capital. "In the past it was impossible to start those types of businesses because capital was very limited, and it was hard to buy the necessary machines and create new products. There is a lot more opportunity now, and the starting point for innovation is moving forward."

The Mercari effect

Another boon to VC confidence in 2018 came in the form of Japan's first major IPO for a venture-backed company as flea market app Mercari raised about $1.2 billion. The offering facilitated partial exits for groups including Globis Capital Partners, Global Brain, and East Ventures. The company was worth about $3.7 billion at the time of the float. The valuation surged to around $7 billion during a brief honeymoon and has held steady around $4.1 billion in the past few weeks.

For the sake of overall industry sentiment, there is significant pressure on Mercari to continue performing, especially as the company pursues a high-stakes US expansion plan that is generally considered to be stalling. None of Japan's earlier internet successes have succeeded in achieving truly global branding, including previous IPO darlings with comparable business models and US ambitions such as social networking service Mixi.

"Mercari has changed the culture in terms of being a Japanese tech company with a global mission," says Batara Eto, a co-founder and managing partner at East Ventures who also co-founded Mixi. "Japan had some of the best global consumer tech companies a couple of decades ago, but we don't really see new players coming out recently. The biggest challenge for Japanese start-ups is how can they become the next Sony or Nintendo."

To some extent, taking Japan VC to this level will depend on how start-ups build and evolve their business models. There is an established playbook for the global expansion of Japan-branded gaming, media and entertainment, but the enterprise software and B2B plays that many VCs are currently prioritizing have yet to prove capable of this traction.

Skepticism that such expansions are needed to drive venture market development usually points to the fact that, even in the US, global footprints are the exception, not the rule. But if Mercari is to be an effective poster child, it may need to diversify beyond its C2C roots. "The competition outside of Japan is tough if you don't have a really good cash cow at home," says Eto. "Start-ups in Japan need to get more revenue inside Japan by going after other verticals before they go outside the country."

In the end, Mercari's strongest legacy may have more to do with its ability to realize sizable later-stage rounds when it was still under private ownership. The company raised $117 million across five rounds, including a $75 million Series D in 2016 that established it as Japan's first unicorn. Now some of that capital has made it back to investors, institutional LPs including the world's largest pension, the Government Pension Investment Fund, are developing a taste for pre-IPO risk.

"Since the recent IPO successes of Money Forward, Raksul, and Mercari, Japanese pension funds have seen evidence that this market is capable of providing solid returns," says Kyohei Mukaigawa, an investment manager at DNX Ventures. "At the same time, largely due to the low interest rate environment, they've been changing their portfolio allocations to increase exposure to alternative assets such as private equity, real estate and infrastructure. Now, finally, they seem to be interested in VC."

Mukaigawa added: "That's really exciting for the whole industry because there's a lot of money waiting there, even if they only deploy 1% of it to VC."

DNX, which recently rebranded from Draper Nexus Ventures, is putting this observation to the test by trying to raise half of the money for its $300 million third fund from institutional investors. Fund-of-funds, life insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds are part of the mix so far, but domestic pension funds – the key ingredient in getting the industry to critical mass – remain the toughest sell. To cross this line, it may be necessary to instigate more later-stage activity via some creative GP-LP dealing.

Institutional heft

In another example of 2018 being a turnaround year, Japan Post Investment Corporation (JPIC) stepped in to fill this role. This entity was formed by Japan Post Bank and Japan Post Insurance when they decided to introduce a direct investment capability to complement their portfolios of LP commitments. JPIC has gone on to hire venture veterans from Fidelity Growth Partners and Mitsubishi UFJ Capital to deploy an initial allotment of $324 million targeted at the growth-stage gap in local technology markets.

Lower profile organizations are playing similar balancing acts across the development stage spectrum. Shinsei Bank, for example, began participating in venture last year in both an institutional and strategic capacity with the launch of a new division that aims to be a technology R&D center and an ecosystem support team for the firm's various direct and fund-level investments. This includes an LP position in the latest vehicle from Coral Capital.

"We want to focus more on our home market because Japan's start-up and technology markets need more support from licensed financial institutions," says Yasufumi Shimada, chief architect and executive advisor at Shinsei's Innovative Finance Institute. "One of the reasons we chose Coral was because they look at the whole digital ecosystem for transforming Japan's legacy industries – not just fintech. We want to support that innovation of society as both a financial partner and through infrastructure system involvement."

Japanese strategic investors are becoming aggressive about innovation in financial services, automotive, and consumer electronics in particular, but telecommunications is perhaps the only sector where the phenomenon has triggered competitive instincts. Internet and mobile carriers NTT Docomo, Line, and KDDI appear to be using corporate venture arms and domestic M&A more directly as part of a scramble for market share than their counterparts in other sectors.

KDDI has taken the lead in this regard, dabbling in acceleration with its Labo program and teaming up with Global Brain on a string of VC funds, the latest of which earmarked about $190 million for investment in Japanese technology relating to 5G. Most significantly, it has started buying companies such as Soracom, an internet-of-things player spun out from NTT Docomo in 2014 and backed by several independent venture capital firms, including Infinity.

VC stakeholders hope this activity will translate into a bigger domestic M&A trend that diversifies the exit market. The thinking is that the cultural bridge was crossed when strategics decided to fire up their VC arms, and the jump to making acquisitions will therefore only be a matter of letting competitive dynamics take hold. But this process can take several years to unfold. For example, it is only relatively recently that Chinese tech giants became comfortable swooping on whole companies. Before that, they pursued strategic agendas through in-house development and a smattering of minority deals.

"LPs looking at VC funds in Japan will be more confident if they see multiple paths of exit, so that will continue to be a gating factor for a lot of companies and investors," says David Milstein, head of Japan at Eight Roads Ventures. "We're always cautious of that because there are a lot of external risks involved in an IPO. What is really going to tip this market is when the corporates move from strictly venture investing to actually becoming acquirers."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.