Australia co-investment: Too close for comfort?

Most Australian institutional investors want to participate in deals alongside private equity managers, but few have the bandwidth to do it effectively. Recruitment and risk controls are the key obstacles

Private equity has paid off for Future Fund. Unusually among institutional investors of its size, the Australian sovereign wealth fund has built a A$20.6 billion ($14.7 billion) portfolio that is heavy on commitments to VC and growth managers as well as to co-investments. These two areas accounted for nearly two-thirds of capital called in the 12 months ended June 2018. The 10-year return on PE is 17.3%, which has helped Future Fund comfortably beat its performance benchmarks.

Crafting this blend of exposure is not straightforward and expertise comes at a price. When three of the four most senior members of Future Fund's private equity team departed three months ago to launch their own consulting firm, compensation was said to have been one of the motivating factors. At a time when many LPs in Australia are looking to turn their co-investment dreams into reality, it raises the question of whether the industry is capable of recruiting and retaining the requisite talent.

"If you are a superannuation fund CIO, certain asset classes are easier to internalize than others. As you move up the spectrum and into more complex transactions and operationally intensive assets, you need more resources around origination," says Michael Lukin, a managing partner at ROC Partners. "If more areas get internalized, will the remuneration structures reflect what the private sector management industry pays people?"

LP interest in co-investment is a global phenomenon, driven by a desire to develop internal investment capabilities, exert more influence on the outcome of allocations to illiquid asset classes, and reduce the overall cost of private equity, assuming it is available on a zero-fee basis to LPs in the related fund. The emphasis on cost is arguably heavier in Australia than anywhere else.

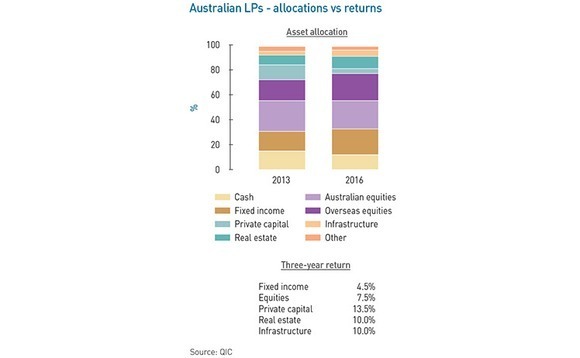

It is the world's fourth-largest pension market with A$2.8 trillion in assets yet the average allocation to private capital fell from 12% to 4% between 2013 and 2016, despite outperforming all other asset classes during that period. This discrepancy exists largely because more attention is directed to the fees external managers earn than to the returns they produce. Co-investment can help bring down the cost of private equity, but LPs need to find a way to get exposure to the asset class that works for them.

Modes of engagement

While the trend among larger institutional players is to bring more investment capabilities in-house, private equity is usually the last to be addressed – if at all. Cbus, for example, already has a team for direct real estate and more staff are being recruited for infrastructure and debt in order to ease reliance on third-party managers. IFM Investors is still responsible for most of the infrastructure portfolio, but the next step is for Cbus to be a part-owner and manager of assets.

The superannuation fund uses intermediaries to get private equity exposure, and even that is dwindling. While ROC Partners retains a mandate for fund commitments and co-investments domestically, allocations to international managers have ceased. "Given the extent of change we have committed around in-house investing I think we can get more bang for our buck by building up our infrastructure capabilities than trying to pursue private equity," Cbus CIO Kristian Fok told AVCJ last year.

Outsourcing to the likes of ROC is one option. Separately managed accounts – which now account for 80% of ROC's assets under management – offer a customizable mix of primary, secondary and co-investment exposure, drawing on the manager's network of relationships with GPs. Groups that don't want to pay the fees and prefer to go it alone can either buy a portion of the equity syndicated by PE firms once a deal is done or get involved in a live process and co-underwrite the transaction.

Few Australian LPs are capable underwriters, able to conduct due diligence and sign up to a deal within a relatively tight deadline. QIC and IFM, which manage some or all their capital on behalf of institutional clients, sit in this category, as do the likes of MLC Private Equity and Future Fund. Sunsuper and First State Super are described as more recent joiners, having hired people with relevant experience.

In most cases, co-investments are handled by the same team that makes primary fund commitments or by dedicated co-investment professionals who sit alongside these teams. AustralianSuper takes a different approach. Equities, whether public or private, are divided into tiers based on size, with portfolio managers and analysts responsible for each one. They assess PE co-investment opportunities, working with transaction specialists where appropriate, according to industry participants.

There have been two instances in the past 12 months where AustralianSuper – the largest player in the country's pension space with A$145 billion in assets – has leveraged its public markets heft to try and bring about private markets outcomes. When BGH Capital offered to privatize Healthscope and Navitas, the superannuation fund said it would vote its shares in favor of the bids and contribute additional equity. The first transaction failed while the second is in process, having won board support.

Coming into these situations with a detailed understanding of the companies and industries involved effectively meant AustralianSuper saved on time and resources. The intensity and nature of its engagement was different from that of Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan (OTTP), Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) and GIC Private. These three heavily resourced co-investors also took part in the Healthscope deal and dispatched multi-person teams to Melbourne to work on it.

"AustralianSuper is more opportunistic – if companies are underperforming or they like a certain theme, they might be open to privatizations," says one source who has worked with the superannuation fund on co-investments. "That doesn't mean they will aggressively chase lots of deals. They will do more than they have in the past, but at present they are not of a mindset to be like the Canadians or GIC."

Money matters

Being like OTPP or CPPIB is not a modest ambition. The two pension funds can commit resources to a co-investment from early in the process because they are willing to pay up for the right people. It is generally acknowledged that the compensation packages available at Australian superannuation funds are considerably smaller, and this could be the single biggest obstacle to the development of meaningful co-investment programs managed in-house.

"Compensation depends on the structure of the institution. If you are a public entity it can be very hard to pay market rates because you are very visible in terms of your accounts," says Marcus Simpson, head of global private capital at QIC. "Institutions are also aware that if they build a program that is specialized and manually intensive and the team leaves, they are stuck with it."

While the basic pay a principal or managing director receives at a private equity firm is likely to be more than they would get from a superannuation fund, the key differentiator is carried interest. The assortment of investment executives in Australia working on a deal-by-deal basis are testament to this. They generally don't have the management fee streams and supporting infrastructure of a traditional GP, but the pay-off from originating and managing deals on a stand-alone basis is reward enough.

In one instance, a superannuation fund hired someone from the GP side only to see him depart shortly thereafter; he had received a carried interest check from his previous employer and decided to enter semi-retirement. Not all PE executives have track records that are likely to deliver substantial windfalls, but such individuals might not have the skills to run a pool of co-investments. Hiring the wrong person could be more damaging than not hiring anyone at all.

There are workarounds to suboptimal compensation. Superannuation funds can look for talent lower down in a GP – targeting executives who are a couple of funds away from receiving meaningful carried interest entitlements – or bring in people who have done aspects of direct investing from accounting firms, law firms and investment banks. Together, they cover all the bases and then grow as a team.

However, the problem then shifts from recruitment to retention. In time, a successful team or individual might find that their track record can be properly monetized elsewhere. "These funds have salary bands and bonus bands they need to keep to, and they can't offer equity in their business," says ROC's Lukin. "There is that challenge of trying to retain staff when you can't necessarily use all the levers that a private business would use to retain staff."

The trickle of movement from the GP to the LP side suggests the message has been received. According to several investment professionals who have been approached about positions with super funds, compensation packages sometimes include a phantom carried interest component. Frazer Wilson, a partner with Heidrick & Struggles in Sydney, concurs that efforts are being made to "apply more innovation to a carry-like structure," but the level of activity varies by institution.

At the same time, money isn't everything. MLC and QIC have both built up sizeable private equity teams that include people with direct investment capabilities. Compensation is said to be structured with a view to narrowing the carried interest gap, but choosing to work for an LP is also a lifestyle choice.

"We've hired and interviewed people from the manager side and the cultures are often very different. On the manager side, you are working incredibly long hours and the pressure is high, but there are more red carpets, offices with windows, and dedicated parking spaces," says QIC's Simpson. "We attract people who are not just focused on economic outcomes. Our investment team get to evaluate opportunities in the US, Europe and China, as well as Australia, so they get a global outlook. We also do funds, co-investment, and secondaries as one team."

Institutional ballast

An established platform is another consideration. When Simpson joined QIC in 2005 there was no private equity portfolio. Building from the ground up was made easier by the existence of a substantial back office operation from more than a decade of direct investment in real estate. There were already internal teams covering risk, environment, social and governance (ESG), and economics, as well as staff who were familiar with legal and tax structuring.

Not all groups have the same foundations. One investment professional who operates on a deal-by-deal basis recalls presenting an opportunity to a superannuation fund and being told that it would be considered at investment committee. When pressed for more detail, the fund admitted that it had never assessed a private equity deal before and none of the processes or protocols were in place.

Even if there is real estate or infrastructure investment experience that can be drawn upon, it does not cover all eventualities in private equity. With an infrastructure project, there are upfront agreements between the investors, contractors and unions around costs, timing, and working conditions. PE investments have more moving pieces. If a superannuation fund has direct exposure to a company that decides to move its manufacturing from Australia to overseas, there could be political fallout.

"If you haven't been able to build a team internally to make decisions on funds, I'm not sure how you are going to be able to manage it with co-investments. The degree of complexity goes up significantly with co-investing, and then it goes up again with direct deals. The risk rises as well because you start bringing reputational risk into it on the frontline of transactions," says Steve Byrom, co-founder of Potentum Partners and previously head of private equity at Future Fund.

LPs that don't want to be so close to the assets must decide how much they are willing to pay others to do it for them, and on what terms. IFM wants to position itself in between direct exposure and the ROC-style separately managed account, where deal flow is largely dependent on what comes through the GP network and the level of discretion granted to the manager varies. The product is a managed account, but it only makes direct investments, and LPs can sign-off on which companies to back.

IFM, which is owned by 27 industry superannuation funds, already performs a similar function in infrastructure. It is essentially trying to take the leap into private equity that is beyond many of its clients by leveraging the existing IFM platform and hiring people from the GP side. Key aspects of the offering include: customization, deal pipeline visibility, and built in liquidity features so LPs have more control over what they are getting into and when they will get out; and fees set lower than the traditional 2% management fee and 20% carried interest.

Adrian Kerley swapped a GP for an LP role in 2016 in moving from CHAMP Ventures to Commonwealth Superannuation Corporation, and now he has returned to direct investment with IFM. He believes the conversation on co-investment has moved past fees, at least among larger LPs. If the illiquid portion of a portfolio has the greatest capability to generate alpha, it should be the most dynamic source of equity risk exposure. A blind pool fund doesn't allow for enough control over portfolio construction.

"Coming from the LP side, I saw the market was moving towards that – whether it is GPs giving dollar-for-dollar co-invest to fund investors, industry funds utilizing wholly-owned investment managers like IFM, or sovereign wealth funds looking to set up joint entities to do larger deals that are held for longer," Kerley says. "One of the attractions of IFM is the clients run alongside us with some level of control. It is a highly aligned business model."

The challenge is getting people to buy into the concept. IFM has completed only four direct deals so far and is said to have gained limited traction with investors. Critics question to what extent the model is about control rather than cost, noting that the fees paid for private equity exposure are not the key determinant of performance. IFM clients counter that they can recognize situations where there is a trade-off between cost and quality.

Competition also comes into it. A new entrant must establish itself as a credible player in the eyes of vendors, management teams, and the entire ecosystem of intermediaries and service providers who bring deals to private equity firms and ensure they transact smoothly. If the owner of a highly desirable asset instructs a bank to set up a limited auction with three participants, it is difficult to supplant GPs with 20-year track records from the top spots on the call sheet.

The people factor

This underlines how investment is very much a relationship-driven business – and it applies at the fund level as well as the deal level. The departure of a key individual might not be enough to disrupt a well-established LP private equity program, but what if that person spends four months of the year overseas and channels 50% of new commitments into co-investment?

Moreover, as the world's largest investors concentrate their efforts on a smaller number of top-performing GPs, looking to deploy more capital with each one, the battle for co-investment allocations is intensifying. Australian LPs that are not writing big checks for funds might struggle to get into deals.

By specifically targeting situations in which it can account for a significant percentage of mid-size funds, First State Super is said to have found a way to ensure that its voice is heard on governance issues and its name is first on the list for co-investment. But dealing with firms that might be earlier in their lifecycle, with less institutionalized processes, makes it even more important to have competent people overseeing these relationships.

Put simply, these are high stakes games and not everyone is ready to play – a view endorsed by MLC CIO Jonathan Armitage when asked why private equity is among the last areas in which LPs are considering in-house management and direct exposure. "I think that is because the dispersion of returns within private markets is much higher than other asset classes and so the cost, if you get it wrong, can be very high," he says. "It's important not to be just taking on more risk when making co-investments."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.