China's sharing economy: Shared dilemma

With Ofo teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, bike-sharing and the broader concept of the sharing economy in China is being called into question. The survivors will be sustainable and suitably differentiated

Not long ago, bike-sharing was lauded as one of China's new "four great inventions," sharing a platform with high-speed trains, mobile payments and e-commerce as the 21st century equivalents of ancient breakthroughs involving paper, the compass, gunpowder and printing. With such compelling evidence of an ability to develop innovative technology-based business models, the country could shrug off its unwanted reputation for copycatting ideas from overseas.

At the peak of the excitement, the state-owned People's Daily singled out Ofo, founded by Peking University postgraduate student Wei Dai, as a new generation national hero that had "stepped onto the global stage." Less than two years later, the same publication ran an editorial denouncing Ofo as the company's coffers ran so low that it struggled to refund deposits of customers who had paid to use its bikes. The episode cast light on weak governance at the start-up, and in the industry as a whole, People's Daily claimed.

This dramatic shift in attitude reflects the rapid turn-around in Ofo's fortunes. The sustainability of its business model – characterized by raising large amounts of private funding to produce hundreds of thousands of bikes, subsidizing users in certain locations in order to grow market share and offering no clear sightline to profitability – has been questioned too many times. It has left bicycle suppliers threatening legal action over unpaid bills and customers clamoring to get their deposits back.

Ofo owes at least 13 suppliers a combined RMB110 million ($16.2 million), while Dai has been listed as a defaulter and barred from taking advantage of executive perks – including flying business class and sending his children to expensive international schools – Chinese court documents show. Moreover, Dai admitted in a letter circulated internally that Ofo was on the verge of a bankruptcy and he now must "break every renminbi into three."

Before the business unraveled, Ofo and its direct competitor Mobike were champions of the sharing economy model, which sold to investors as having untold potential given the size of China's population and the untapped demand for various local services. Between 2015 and 2018, Ofo raised more than $2.2 billion across eight rounds, with Alibaba Group and CITIC Private Equity among the participants. Meanwhile, Mobike received over $1.1 billion from the likes of Hillhouse Capital and Sequoia Capital China, before it was finally bought last year by Meituan-Dianping for an equity valuation of $2.7 billion.

Now, though, investors are asking whether bike-sharing can be economically viable. There is similar disquiet about the broader sharing economy space – which attracted RMB216 billion in private funding in 2017 alone, In retrospect, the Mobike transaction represents a high point. Given the noticeable weakening in sentiment among public and private investors, hopes for trade sales or IPOs in the near term are slim.

"A lot of start-ups were playing this ‘pass the parcel' game, ignoring their fundamentals and simply expanding through the cash-burning model, and wishing someone could eventually bail them out at a good valuation," says Peter Mao, co-founder of Panda Capital, which backed Mobike for three rounds until 2017. "They couldn't carry on playing this game forever."

Hot wheels

Ofo and Mobike were both founded in 2015, though came about in rather different ways. The former started out as a student project aimed at fellow students and supposed to be restricted to campus. But by the end of 2017, it claimed to have rolled out services in 150 cities across four countries with 6.5 million bikes and 100 million users. The latter, launched by former business journalist Weiwei Hu, was always intended to be a mainstream commercial venture. By 2017, it also claimed to have 100 million users, as well as five million bikes in over 100 cities.

Ofo requires users to put down a deposit of around RMB99 to join the platform and are then charged RMB0.50 to RMB1 for every 30 minutes spent on one of its bikes. Mobike charges similar rates for its standard service and less for Mobike Lite version. The deposit system was scrapped last year following the acquisition by Meituan-Dianping.

The two companies are functionally the same. Customers identify a vacant bicycle through a mobile app, reserve it, and then use the same app to unlock the machine. On reaching their destination, they park and lock the bike, and pay for the journey through a mobile transaction. Company marshals are assigned different zones in a city, ensuring that bikes are moved from areas of low demand to high demand and broken machines are brought back to the warehouse for repairs.

The initial key differentiator was the cost of the bike: RMB3,000 for Mobike version RMB300 for Ofo. Mobike's machines came equipped with smart locks and GPS tracking systems, but they had to be cycled at least one hour a day to charge up the battery that powered these functions. Ofo minimized costs by using mechanical locks – customers scanned a barcode, received a code, and spun the lock to access the bike.

In theory, this meant one company returned the cost of capital invested in each bicycle faster than the other, but both ended up moving to a middle ground. The Mobike Lite arrived in 2016 with a lighter frame and battery, reducing the cost per unit to around RMB800. Meanwhile, Ofo introduced its own smart locks and tracking systems, increasing the outlay to RMB500. In addition, the companies must cover bicycle maintenance and the costs of running the technology platform, among other expenses.

Competition was fierce because bike-sharing is fundamentally an asset leasing business run according to a simple unit economics model: if they could achieve critical mass in terms of volume and usage, revenues would begin to outweigh costs. This was one of the reasons for expanding overseas so quickly. At one point, Ofo and Mobike were each in 20 or more countries, their colorful bicycles – in yellow and orange, respectively – found as far afield as Israel, Australia, the UK, Singapore and Japan.

However, last year they started to retreat from certain jurisdictions. Mobike's exit from Manchester in the UK attracted headlines as the company said that thefts and vandalism had made the business untenable. But the overriding issue, for Ofo and Mobike, was that they had sought to become too big too fast. They entered new markets before proving the model worked in their home market, and so the combined cost of expansion, maintenance and amortization far exceeded revenue.

"Some of the initial calculations made by investors were too simple. They expected that a bike could be used for three years to fully recoup the cost of it. However, it turned out the bikes couldn't last for more than six months due to many factors, so the costs have been hugely underestimated," says Maggie Tan, one of the founding members of Uber China.

A viable future?

Following last year's IPO of Meituan-Dianping, a picture of Mobike's operations has gradually emerged. The company generated RMB147 million in revenue from 260 million rides in April 2018, which works out at RMB0.56 per ride. But amortization and operating costs came to RMB396 million and RMB158 million, respectively, leading to net loss of RMB407 million. Fleet size appears to have declined as well – Mobike had 7.1 million bikes in April, compared to nine million in March – while there were only 48 million active users out of a claimed global registered user base of 200 million.

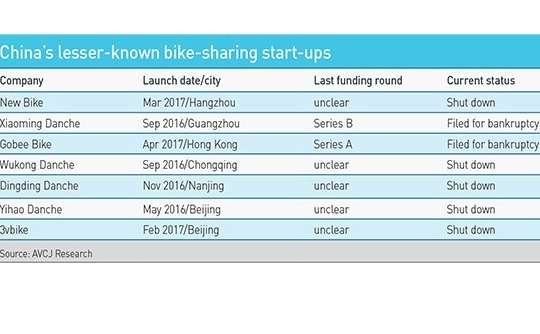

Still, thanks largely to their substantial private funding, Ofo and Mobike have outlived their peers. The number of bike-sharing start-ups in China peaked at an estimated 40 and there have since been some reasonably high-profile failures. Bluegogo, which at one point expanded into San Francisco, went bankrupt in 2017 and its assets were acquired by ride-hailing company Didi Chuxing, so its blue bicycles remain in operation. Dozens of others have either shut down or disappeared from the public view.

This does not mean bike-sharing has no future in China. Due to the heavy traffic in major cities, there is a need for alternative and flexible ways to commute. The percentage of journeys made by bicycle increased following the introduction of sharing services, suggesting that people were switching from other modes of transport to shared bikes. It also solves a pain point: riding to work on a personal bike means committing to a two-way journey; if someone wants to go out with friends after work, either they are the only person on a bike or they leave it at the office and they don't have it the next day.

"The demand for this service is still there. Imagine you want to go to a bank that is a 20-minute drive from your home but you cannot get a cab – isn't jumping on a bike the best solution? These services have solved the last-mile traffic problem. Meanwhile, the number of deposits could be four of five times the number of bikes, so companies can generate very healthy cashflows," said Panda Capital's Mao.

This raises the question as to what represents the best way forward for bike-sharing. Non-profit, government-run services have gained traction in China, much like other markets, although the machines are often of lower quality and not dock-less. For an independent player, an alliance with a larger platform, along the lines of the deal involving Meituan-Dianping and Mobike, makes sense to many industry participants.

"The Meituan-Mobike deal was good for all parties involved. Mobike found a good home for its assets and Meituan gained an important part for its ecosystem. Meanwhile, by having Meituan as a strong shareholder, Mobike can continue to finetune its business whereas Ofo is left to worry about where to get its next round of financing," says Jeremy Choy, head of M&A at China Renaissance, which advised on the Mobike-Meituan transaction.

As Ofo and Mobike grew, there were plenty of rumors about a potential merger. This had already happened in ride-sharing and online-to-offline (O2O) services once two dominant players emerged and large amounts of private funding was essentially being channeled into user subsidies. But a deal never happened and the speed with which bike-sharing became a proxy for the Alibaba-Tencent Holdings battle is one possible explanation.

Tencent is a shareholder in Meituan-Dianping, as well as a strategic partner and frequent co-investor. Given Tencent's early backing of Mobike, if Meituan-Dianping wanted to add bike-sharing to its O2Oservices offering, there was one logical choice. Meanwhile, Alibaba invested in Ofo and there have been repeated reports that it or Didi, which is seen as aligned to Alibaba, would buy the business.

However, Ofo's options appear to be narrowing. While Didi picked up the remnants of Bluegogo, Alibaba affiliate Ant Financial has invested so much in Hello Bike – a Shanghai-listed newcomer that targets mainly lower tier cities – that it is now the controlling shareholder. Dai's internal letter also noted that the company had failed to raise funding in the past six months. "While it's less likely that the company will continue to get financing, there could be an M&A or a disposal of assets but it's hard to say how and when these events could happen," says Jixun Foo, a managing partner at GGV Capital.

Strength in numbers

The fact that Didi was touted as a possible acquiror of Ofo is confirmation that not all aspects of the sharing economy are busts. The company's most recent documented funding round in late 2017 was completed at a valuation of $56 billion. Didi claims to be the world's largest mobile transportation platform, connecting over 450 million registered users with 21 million drivers in China and facilitating about 25 million rides every day. Short-term rental platforms in the style of Airbnb have also established themselves, with the likes of Tujia and Xiaozhu receiving considerable PE backing.

These companies differ from bike-sharing players in several respects. First, they are not leasing businesses, so a different set of unit economics apply. Rather than buying cars and hiring drivers, Didi is taking an existing resource and putting it to more efficient use. It could be argued that co-working space providers like WeWork and Ucommune have more in common with the Ofo model – they bear the costs of inventory – but the assets are of higher value and there are more ways to customize services.

"At the end of the day, sharing economy assets must make sense, which usually means they must be of high value. If the asset value is too low, then the benefit of sharing them and the value that is created by sharing them could be very low," explains GGV's Foo.

Indeed, businesses lower down the value chain than bike-sharing have run into difficulty. The sharing model has been applied to umbrellas, power banks and clothes, largely without success. Horror stories abound. An umbrella-sharing company lost every unit of its inventory within a day of launch, while two power-bank sharing businesses publicly attacked each other last month, with one accusing the other of misusing customer deposits and offering pirated Apple products, according to local media reports.

But it is not just a matter of value, but also basic functionality – a business model has to make sense. "The irony here is that while power-bank sharing companies adopt a similar approach to bike-sharing, allowing users to locate available power banks via a mobile app, the users that need this service probably have no battery power left in their phones, which poses the question of how they can use the app," says one China-based investor.

The key takeaway is that sharing economy businesses do make sense, provided they are sustainable once criteria such as capital investment, maintenance costs, addressable market size, and frequency of usage are considered. There is plenty of white space in China's O2O services industry, but so far relatively few can claim to have achieved sustainable critical mass. High-profile failures simply underline the importance of running thorough due diligence.

"LPs are becoming more cautious about where they are putting their money and this is driving change on the GP side," says Siew Kam Boon, a partner at Dechert. "We are seeing more ‘smart money,' meaning investors are going back to focusing more on companies' fundamentals."

Needless to say, the businesses that stand up to scrutiny will be those that are not pursuing a generic sharing economy model, but looking for ways to differentiate themselves from the competition. "I am bullish on verticals such as education," says Tan, formerly of Uber. "Bike-sharing is more like a standardized way of sharing because the bikes are the same, whereas in the education space, one could charge a premium by offering a more customized experience, such as a platform that connects users."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.