Venture capital: The battle to be different

VC fundraising has been on a roll in Asia as managers raise larger sums to address fast-growing investment opportunities. GPs must consider what – and how much – makes them stand out from the crowd

Xiaodong Jiang describes 2016 as the "winter of fundraising for China VC." After a decade at New Enterprise Associates, he had spun out to form Long Hill Venture Capital and the firm was on the road with its debut fund. Long Hill took six months to raise $125 million, but Jiang was peppered with questions about rising valuations and bursting bubbles from LPs that were wary of the China market.

The firm spent half as long raising more than twice as much money for its second fund, which closed at $265 million last July, but it wasn't necessarily easy. The message from investors was: everyone is fundraising, we don't have enough time. Long Hill had to fight for the attention of LPs preoccupied with re-ups for managers scaling up from $500 million to $1 billion.

While the dynamics are different, some themes are unchanged. "Two years ago, too much money was going in; this time, people are raising larger funds," Jiang told the AVCJ Forum in November. "Investors are becoming increasingly worried and they want to know how you are differentiated."

For Long Hill, differentiation comes through specialization – it focuses on early-stage tech-enabled healthcare and consumer plays. Other firms have different answers, but they are being asked the same question: What makes you stand out in a market characterized by abundant capital, ever larger rounds, and companies staying private for longer? GPs must think carefully about their positioning, the amount of capital they need, and where it comes from.

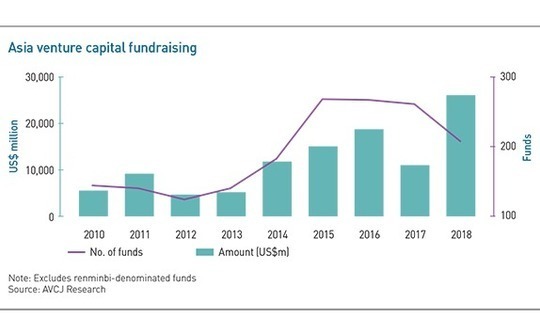

Asia-focused venture capital managers raised $34 billion in 2018, according to AVCJ Research. Strip out the renminbi-denominated funds and the total comes to a record $25.9 billion, nearly two-and-a-half times the 2017 figure. China, Japan, India, and Southeast Asia all saw new fundraising highs.

VC investment in the region, which includes activity by managers from outside Asia, reached $21.1 billion, down slightly on 2017. However, the amount of capital entering the broader technology space rose by over 50%. A total of $59.2 billion went into growth stage deals as private equity funds, sovereign wealth funds, hedge funds, and VC players with later-stage funds plowed money into new-economy plays.

Asia isn't the only region on a roll. "This year in the US we will do $40 billion of fundraising, which is reasonably good given we were above that two years ago and it does feel like things have tapered off a little bit," said Scott Kupor, a managing partner at Andreessen Horowitz. "But five years ago, we were doing $25 billion. As that number eclipses $50 billion and if we get back on a trend line where we are moving to the $100 billion number that we saw in 2000, there would be more cause for concern about how it might impact pricing."

Cyclical vs structural

While it is generally accepted that VC is cyclical, all kinds of structural factors are used to justify the phenomenal growth in activity seen in Asia.

For Tony Zhang, a partner at growth-stage tech investor Jeneration Capital, the maturity of the Chinese market is a source of encouragement. Investors have a decade's worth of data to work from, while entrepreneurs have evolved from business model copycats to innovation leaders. The likes of Australia and Japan can't match China for scale, but investors say these markets are at a tipping point, with a host of unicorns in the pipeline that have sought to establish a global footprint from inception.

India has surpassed the US in terms of internet users and smart phone users, while Flipkart sits at the head of a growing list of exits for local VC investors, through secondary sales as well as M&A. "When we started we didn't plan for companies reaching $1 billion valuations, we used to say anything in the $200-300 million range would be a good return," noted T.C. Meenakshisundaram, founder of Chiratae Ventures.

Southeast Asia has also overtaken the US by internet user numbers in the last year. Much like India, it can look forward to a period of rapid economic expansion unencumbered by the need to upgrade existing technology infrastructure – the relatively young populations of these countries are brought up mobile and digital. As many as 25 unicorns are tipped to emerge in Southeast Asia over the next five years, up from the current total of about 10, but a relative lack of competitive intensity might be even more significant for investors.

Ahead of its 2017 investment in credit-socring technology start-up Kredivo, Jungle Ventures mapped out the payments and consumer lending space in other markets. The GP found 200 companies in China pursuing a similar business model to Kredivo, of which 50 had VC investors. In India, 20 out of 43 comparable businesses had financial sponsors. Kredivo was the only company of its kind in Southeast Asia and now it has just one competitor.

"For every sector we invest in, we don't see more than one or two competitors," said Amit Anand, a founding partner at Jungle. "There is a scarcity of good quality assets, so once you see a company that scales quickly and executes well, every investor wants to ride that horse. There is a fair amount of euphoria on the downstream capital side and it's not going away. But as the ecosystem becomes more diverse, with more capital at the early stage, more companies and more unicorns, there will be a bit of a correction."

This intensity varies between jurisdictions in the region. China sees more competition than most and anecdotal evidence suggests that certain segments are under pressure. However, Wei Zhou, founding and managing partner at China Creation Ventures (CCV), claims "the panic is mainly from late-stage investors because there is too much money concentrated there." He describes China's VC space as an inverted pyramid, with far fewer funds of $300 million and below than $500 million and above. CCV closed it debut early-stage vehicle last year at $200 million.

Avoid the crowds

For investors that target growth and later-stage rounds, the objective is to avoid the crowds that congregate around low-hanging fruit. Jeneration, which is said to be raising an $800 million fund, categorizes start-ups into one of three stages of development: identifying the right business model, expansion, and the pre-IPO push for scale. It focuses on the middle stage, which until a few years ago didn't really exist because companies went public earlier in their lifecycle.

"We will see more and more companies staying private longer and the capital base will become more comprehensive as well," said Zhang. "We are a beneficiary of the mega funds and mega rounds. On one hand, these funds can provide an exit channel. On the other, these investors raising mega funds are not stupid. They are a fresh eye for us to underwrite deals within our firm."

While Jeneration is looking for the next generation of champions across e-commerce, content, and specific technology verticals, the likes of Warburg Pincus and China Everbright increasingly shy away from areas in which Baidu, Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings (the BAT) enjoy dominant positions and getting traction is expensive. The focus is more on enterprise solutions and finding ways in which technology can transform traditional industries.

"There are a lot of champions in the internet industry, which makes it hard for start-ups to grow and become the next Baidu. They would probably get killed or bought during their journey," said Victor Ai, a managing director at China Everbright. "The best way to invest is to find an opportunity to get around the BAT. There are still a lot of areas like agriculture and transportation that aren't disrupted by technology. Find the right companies in those verticals and they will become the next BAT."

This strategy applies to other Asian markets as well, even though they are less developed from a start-up perspective. Khailee Ng, a managing partner with 500 Startups, argues that the future unicorns in Southeast Asia will have business models that apply deep technology in areas where previously smart phones had no reach. For example, 500 Startups recently backed a company that develops smart feeding systems for fish farmers in Indonesia.

The challenge for venture capital investors is making sure they stay relevant to entrepreneurs and LPs in this changing environment. Post-investment services are increasingly part of entrepreneur engagement in Asia, whether it involves serving as a high-level sounding board to founders or utilizing internal resources and external resources to help with recruitment, marketing, and finance.

Asia isn't as developed as the US in terms of VC post-investment, and no one can match Andreessen Horowitz for scale – two thirds of its 150 headcount focuses on post-investment – but GPs in both markets still face some similar issues. According to Kupor, one of the difficulties Andreessen Horowitz faces is deciding which portfolio companies require additional help and how to scale back resources for those that do not. At the other end of the spectrum, London-based Balderton Capital must find the best way to leverage the knowledge and networks of a relatively small post-investment team.

These views were echoed by Shinichi Takamiya, a partner with Japan's Global Capital Partners. "As the competition gets fiercer, we are moving more towards the operation layer, but we don't want to be part of a company's operations because in the end, we must exit," he explained. "[At the same time], we have a value-add team, but we can't hire 100 people. We have to leverage outside experts."

Here to stay

On the LP side, it comes down to finding the right partners. Last year, GGV Capital raised $1.88 billion for its seventh China-US fund, which comprised separate vehicles for seed, venture and growth strategies. The undertaking was greater than Long Hill's fundraise, but both GPs prioritized efficiency – they wanted to concentrate on LPs that were genuinely interested while moving on from those that were not.

Transparency was the key. GGV, for example, put together a 100-page presentation that covered its investment history and followed up with a full track record in Excel format. "If an LP received the materials two months ago and then told us they were still looking at it and doing due diligence, that meant they weren't interested so we dropped them," said Teck Loon Goh, GGV's head of investor relations. "If an LP wants to spend time with us, we are there 110%, but you have to build in for some churn in the LP base and let people flow out elegantly."

Investors that are truly committed to understanding the asset class are also more likely to stay involved for the long term. One of the pitfalls in a bullish fundraising environment is it draws in "drive-by LPs" who just want exposure to something. Investors coming into venture capital for the first time, without considering the illiquidity challenges, are often the first to exit once the cycle turns. Asia might be going through an unprecedented period of technological innovation, but extreme volatility or liquidity drying up in certain markets could easily cause havoc.

"Fundraising will get tougher but if you have the returns and have done your work in terms of generating exits, those investors who like venture as a long-term asset class will be there," said Melissa Guzy, founder and managing partner at Arbor Ventures. "But there is an overarching trend that will impact venture going forward – mega funds versus specialty funds. We have seen groups raising mega funds and a convergence between venture and PE. If you aren't that, then you need to have some sort of differentiation that can be demonstrated to LPs."

Perhaps the worst thing a GP can do in these circumstances is try to be something it is not. Fundraising difficulties are often self-inflicted, and with managers raising ever larger pools of capital in a competitive environment, there is a temptation o conform to industry type – to "dress yourself up and say I'm just like the firm that raised a lot of money but I'm better in two ways," as Long Hill's Jiang puts it. But fakers will ultimately be found out.

"When LPs come in, especially to a first fund, they are looking at your passion, your knowledge, your views as to what is going to happen in the market," Jiang adds. "Because VC is such a long-dated asset class it is going to come out – and if you get a reputation for switching your story or misleading LPs, everything will fall to bits. You have to be genuine from day one, and then the right LPs will flock around you."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.