India PE spin-outs: Standing tall

India provides fertile ground for spin-outs by increasingly confident PE veterans, but LP skepticism remains a major hurdle. Managers must demonstrate their investment skills quickly or risk being left behind

The unmet opportunity in India's middle market crystallized for P.R. Srinivasan when he met a local entrepreneur looking for capital to add new product lines to his manufacturing business. Several other investors had taken their turn examining the asset, but Srinivasan, a former India head at Citigroup Venture Capital International (CVCI), soon realized his competitors had barely scratched the surface of the company's needs.

"I asked him how much capital had gone into plant and machinery, how much into tools, dyes, and fixtures, and what is the lead time for replicating the dyes and fixtures," Srinivasan remembers. "I was apparently the first investor who had asked those questions – but I'm an engineer, so I understand how production processes work. And now the entrepreneur remembers me from the five or six private equity funds he has met."

Situations like this were the reason Srinivasan and several former colleagues from Citibank and The Carlyle Group launched Xponentia Fund Partners earlier this year. The GP, which is currently raising its first fund, plans to provide both expansion capital and guidance to promising middle-market companies that the team's previous employers pass on due to the relatively small check sizes involved.

Xponentia is one of a growing number of Indian GPs led by founders aiming to use their experience in prominent venture capital and private equity firms to target emerging opportunities in the country. However, raising capital has proven to be challenging for many managers, with LPs often reluctant to back new outfits no matter how compelling the narrative. Launching a franchise in the face of this hesitation requires variety in fundraising strategy and innovation in communicating competencies.

Trust issues

Paragon Partners is in some ways typical of India's GP spin-outs. Established in 2015 by Sumeet Nindrajog, an entrepreneur, and Siddharth Parekh, a former investment principal at Actis, the firm targets the lower middle market, which is seen as underserved. The founders believed that Nindrajog's first-hand understanding of the difficulties that small businesses face would be a significant advantage when combined with the financial expertise and LP connections that Parekh had formed in his previous role.

"Actis was a well-known brand in emerging markets, and particularly in India at the time, with a long track record," Parekh says. "So those interactions were helpful, and when we met similar investors they were aware of the Actis story."

But Parekh also acknowledges that Paragon faced significant challenges when raising its first fund, which reached a final close last November at $120 million after more than two years in the market. When it came to leveraging those established relationships into fund commitments, the partners found that in some ways they had to begin building trust all over again.

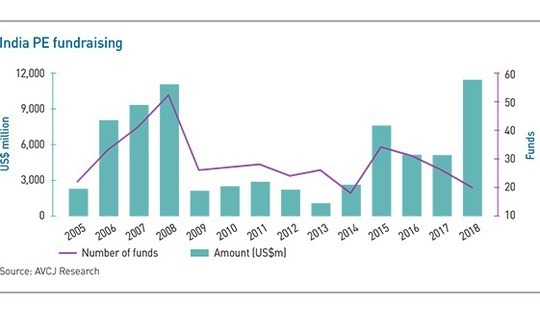

Such headwinds are a common story among India's GP spin-outs, among which prolonged fundraising processes are normal. Data from AVCJ Research bears out anecdotal evidence of LPs' reluctance to join a new manager: while fundraising in India this year has already hit $11.4 billion in final closes – surpassing the previous record of $11 billion set in 2008 – that capital is spread among just 20 funds, the second-lowest annual total since 2005.

Of the managers achieving final closes in 2018, four – accounting for $435 million in commitments – are first-timers: Sealink Capital Partners, founded by former executives with KKR; Helion Venture Partners co-founder Kanwaljit Singh's Fireside Ventures; Iron Pillar, launched by alumni of Morgan Creek Capital Management, Draper Fisher Jurvetson, and Citigroup; and Waterbridge Ventures, founded by a veteran of Actis and Providence Equity Partners. The rest are either from established or overseas investors, such as the pair of $1 billion impact investment funds from UK-based Social Finance India.

"The consensus view seems to be that nobody needs a first-time fund in India, whether it's a spin-out or not," says Niklas Amundsson, a partner at placement agent Monument Group. "International LPs haven't backed these firms to the extent that we've seen them backing spin-outs in China, for example, where it almost seems like anyone leaving a brand-name GP to set out on their own has no issues raising capital."

Diligence questions

LPs are not categorically opposed to spin-outs, as the successes of Sealink, Fireside, and the rest show, and many investors agree that professionals who have cut their teeth at established PE and VC operations are the most logical choice to start new teams. Not only are these individuals already familiar with the PE business model, but their experience can give them crucial insights that would be lacking in someone with an investment banking background.

The difficulty comes when institutional investors are asked to move past the abstract and contemplate the reality of backing a team that has stepped out from its previous support structures to go it alone. In a market characterized by a relatively small population of firms and high turnover compared to other markets, a new manager asking LPs to have faith in his track record will always be met with skepticism.

Assessing a track record with a prior GP remains a tricky proposition. Most founders these days can legitimately claim investment experience, unlike in previous decades when firms might be launched by individuals completely new to the industry. However, the bare facts of a PE professional's career reveal very little about how his character and performance have developed through the years. An investor may have served on the board of a particular company, but what was his actual contribution to its growth, and how relevant is this experience in a rapidly changing market?

"We recently came across a team of individuals that are very well-known in the market, having worked at the mega-funds previously and regrouped to set up a new firm," says Monument's Amundsson. "When we looked at the track record they brought with them, there was quite a heavy skew toward deals that were done 15 years ago, versus deals that were done in the last five years."

In some cases, an LP will have at least some acquaintance with the professional by having invested in funds managed by his previous employer. Depending on the quality of the monitoring, this might be enough to assess the individual's gifts, but in many cases the organization of the GP makes it difficult for the investor to interact with any one person enough to form a suitable impression.

The next level of assessment is to reach out to industry sources to get independent verification of the professional's performance. A wide range of sources can contribute, from members of a portfolio company's management to bankers, advisors, and counterparties involved in a deal. Indeed, Monument aims to contact at least three people to verify the contribution to any given transaction. Investors still need to weigh the responses they receive carefully, however.

"In India you will rarely get a negative reference from anybody, because it's such a small world and people hope to get a favor in return for a good reference," says Nupur Garg, South Asia leader for private equity funds at the International Finance Corporation (IFC). "So as LPs we need the ability to read between the lines, look for inconsistencies, and connect the dots in similar conversations over time."

After all this effort, in most cases the biggest question remains unanswerable: how will an investment professional, used to working as part of a team, handle himself when asked to take on a much larger role as the founder of a new firm? No matter how impressed an LP is by a track record, an investment narrative, and a series of reference checks, in the end deciding to commit to a fund involves taking a gamble.

"Even if the principals have a good track record, there is limited history of them having managed a firm or a fund entirely by themselves in many cases," says Sunil Mishra, a partner at Adams Street Partners. "There are very few people who can say they were the key principals working on end-to-end things, and they will do the same in their new fund."

Of course, investment always involves an element of risk, and LPs acknowledge that seeking absolute certainty of a fund manager's abilities will lead to them missing more good deals than bad. But they also believe just as firmly that the burden remains with the GP to justify their involvement in the fund.

Chicken and egg

Spin-out managers are aware of these concerns and take a variety of approaches to reassure potential investors that they are a good destination for capital. The primary goal is to demonstrate an ability to source and execute transactions, thus showing that they can function outside the umbrella of a large fund.

The contradiction here is obvious – a private equity firm cannot invest without capital. To get around this, a GP may try multiple approaches, each difficult in its own way. Xponentia, for instance, closed its first buyout deal before it began raising its first fund. The founders committed their own capital to the transaction, essentially taking a leap of faith that it would entice LPs to support their vehicle.

Partnering with an existing industry player is another option for a new manager to gain credibility. Kedaara Capital, founded by former Temasek India head Manish Kejriwal and General Atlantic alumni Sunish Sharma and Nishant Sharma in 2011, was buoyed by an early support from Clayton, Dubilier & Rice (CD&R) that was viewed as a vote of confidence that drew institutional investors into the debut fund.

Other founders prefer to wait for commitments from LPs before starting to invest, counting on their personal brands to draw investors into a first close. Once that stage has been reached the firm can start to deploy capital and attract a fresh set of investors.

"Unlike when companies raise money, fundraising is not a one-time exercise: there are multiple closes on a fund," says Rahul Chowdhri, a former partner at Helion and co-founder of Stellaris Venture Partners. "When the people who believed in us earlier gave us our first checks, we could start making investments while we were fundraising, and that becomes a good validation for the next set of LPs."

Meanwhile, an increasing number of Indian spin-out GPs have come to see the country's domestic investor base as a particularly attractive source for a first close. India still has few institutional investors capable of supporting a large fundraise, but commitments from high net worth individuals (HNWIs) and family offices can constitute a powerful endorsement of a new firm, particularly if the investors have some expertise in the GP's target industry or a previous connection with the leadership team.

"If a fund manager raises domestic capital from promoters and entrepreneurs that they have backed in the past, then I think that really boosts their credibility," says IFC's Garg. "On the other hand, if they raise capital from a domestic institution where the primary mandate is deployment, that doesn't really add to the credibility – it does mitigate the fundraising risk, but that's all."

For many Indian GPs, the role of domestic investors is more important from a strategic standpoint than a financial one. Family offices and HNWIs will never represent a large portion of a fund's capital commitments, but they can help to answer the most important question for any fund manager: why should institutional investors support them, and what sets them apart from the competition?

"India is a crowded market, and you really have to identify how you can be different – what value proposition, skills and expertise do you bring to the table that will allow you to generate better returns," says Paragon's Parekh. "That's what investors want to see from a new fund, because otherwise they will continue to back the more established players."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.