India PE outlook: Momentary frights

Investors see potential in India as valuation concerns ease, but exits and the macro picture present challenges in the short term

India's non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) have been a darling of the country's private equity industry for several years. These institutions, which are widely seen as an innovative link between underserved populations and the formal banking system, have garnered considerable investment from various investors, and a number of GPs have even set up their own NBFCs to capture the opportunity.

That enthusiasm was shaken when reports of liquidity issues recently arose in the Indian media, and particularly after Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Service (IL&FS) filed for bankruptcy last month. The government reported that many such institutions suffered from unsustainable business practices, and the State Bank of India has since stepped in to buy nearly INR53 billion ($719 million) in loans from various NBFCs to stabilize the industry.

The unexpected drama around what had been considered a booming area spooked the public and served as a reminder that India is still an emerging economy, but GPs remain confident about investment prospects in the country. "The last couple of months have left people feeling somewhat bruised and battered," says Gopal Jain, co-founder and managing partner at Gaja Capital. "I think when things settle down, people will realize the Indian macro is in a relatively strong position, and I would say one of the stronger macro stories in the world."

PE investment in India has remained strong this year. AVCJ Research has records of 728 deals so far in 2018, on track to outstrip last year's total of 770. Venture rounds continue to dominate, but there has been a notable uptick in buyouts, which have risen from 22 to 30.

Still more impressive is the amount of capital committed across these deals, which stands at $23 billion for 2018, up from $22.7 billion last year and significantly higher than 2016's total of $11.4 billion. Buyout activity grew from $2.8 billion last year to $8.2 billion this year, while VC funding dropped from $8.5 billion to $6.4 billion.

Investors have noted the fall in VC commitments with a degree of relief, not to mention hope that the trend will reflect a much-needed correction in valuations. The increases in recent years have met with growing skepticism. Indian venture investors often continue to support their portfolio companies into the growth stage; investees may see this as a manifestation of their loyalty, but some peers suspect a more mercenary motive.

"When companies come to us for growth capital, we see a round or two by the early investors beyond what should have been done, simply because they're trying to support earlier valuations," says Gaja's Jain. "It will be hard for those investors to make VC-type returns because the earlier rounds were clearly mispriced."

The valuation correction is one aspect of a trend in which Indian VC firms undergoing a reorganization, like Sequoia Capital, have begun to reconsider their investments in the country. Often such firms find that a number of the deals led by departed team members fell outside their core mandate, due to overenthusiastic reactions by the professionals in question to a fad sector.

"Of course, good companies will always tend to attract more investors, and therefore receive rich valuations," says Shilpa Kulkarni, a managing director and co-founder of Zodius Capital. "But when you see everything in the market getting done at rich valuations for even average companies, that's when you need to be disciplined and either sit it out or sell."

This kind of reexamination process can result in investment opportunities for growth capital and private equity investors. As VC firms withdraw their attention from non-core sectors, the companies affected – most of which are fundamentally strong – will seek new sources of capital. GPs often find they have more freedom to negotiate in these situations.

"Valuations in some sectors seem overstretched, but I wouldn't characterize all companies or all sectors are overpriced at this point," says Gaurav Ahuja, a managing director at ChrysCapital. "Private equity is a lot more of a micro than a macro business to us – while macro is important, we have to focus more on individual companies and their market positioning."

Liquidity lags

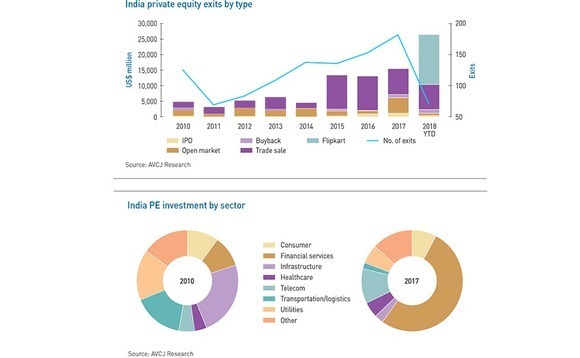

One possible trouble spot in the India PE landscape is exits. The industry has struggled to shed the image that attached to it following the global financial crisis of a country where investors would struggle to realize their investments, and in recent years it seemed to be succeeding. According to AVCJ Research, exits grew steadily from 69 in 2011 to 181 last year. Investors realized $15.4 billion in 2017, up from $3.1 billion in 2011.

"I believe that we can see the India private equity story as being the story of exits for the last two years," says Sanjeev Krishan, India private equity leader with PwC. "With valuations rising, most of the funds active in the market have used this time to exit their portfolio companies."

That story may have hit a snag, however, as AVCJ Research has recorded just 71 exits so far this year. Total capital returned passed $26 million, significantly above last year's total of $15 million – however, this number is skewed by Walmart's purchase of Flipkart in May. Remove this transaction and the total drops to just over $10 billion. Transaction volume has dropped significantly across all exit types, but most precipitously in open market sales and IPOs.

Investors see the growing difficulty with exits as representing in part the effects of broader concerns about the economic situation in India and the broader world. While fears about the growing trade tensions between the US and China are muted due to the considerable opportunities in India's domestic market, some investors are apprehensive about the health of that market.

A common concern is the upcoming general election, which is widely seen as a referendum on the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Uncertainty about the future of the government's aggressive development agenda has made investors reluctant to commit to areas that until recently had seen strong growth.

"There is caution around sectors that have implications from government spending and the like – you are seeing valuations moderate and the number of transactions coming to market start to slow down, especially in areas like infrastructure," says Bobby Pauly, a partner at Tata Capital. "In areas like logistics, which depend on infrastructure, you are also seeing people become more circumspect, even in the listed company space."

Welcome reforms

Despite concerns about the future of the economy, faith in India's growth story remains strong. Reforms like the Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code, introduced last year, are expected to pull double duty for PE by helping reduce the level of nonperforming loans carried by financial institutions while also creating investment opportunities in underperforming companies.

"For a large, complex geography like India to exhibit improvements in ease of doing business, consistency of regulatory reform and the like, I think it still presents a very good opportunity," says Pauly. "The financial inclusion of a vast majority of the Indian population, growing consumerism, and the aspirational mindset of many Indians, all augur well for a very fundamental demand-led India growth story, in spite of the global uncertainty."

Meanwhile, institutional investors, though assured of India's ability to withstand a larger economic storm due to its underlying strength, caution that bets based on overall growth prospects are bound to falter. As always, GPs that can work within India's particular market restrictions and provide unique value to the companies will be the ones that succeed.

"Just because the economy's growing at 10% does not mean that private equity will do well – you still need to see whether the industry structure allows private capital to flourish, and whether there are experienced investors who have the energy and skill to translate that economic growth into healthy returns," says Sunil Mishra, a partner at Adams Street Partners. "On the other hand, while just looking at macro is not enough, if the macro is not good then we'll have a lot of questions."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.