Separately managed accounts: Bespoke buyouts

Co-investment alongside a single strategy is the most common function of separate accounts in Asia, but establishing parameters that meet the needs and rights of all stakeholders can still be challenging

If the concentration of capital amongst larger institutional investors has cleaved the private equity industry into a classed society, few structures underline the division between gentry and proletariat like a separately managed account (SMA). They give LPs who write the largest checks license to write their own ticket: a tailored mandate that could cut across or carve out different asset classes, strategies, geographies, and co-investments.

"When negotiating the terms of a fund, two of the guiding parameters are market practice and legal framework. In general, reasonable limits have developed over time around what is or is not ‘market,'" says Chris Churl-Min Lee, a counsel with Cleary Gottlieb. "With separate accounts, those limits are wider. It is harder to say something isn't market as there is often a high degree of customization. This could lead to many different types of arrangements. There is a lot more room for managers and investors to define the terms of their relationship with each other."

However, this evolving connection between GP and LP does not happen in isolation. The relationship might be defined in bilateral terms, but it has implications for other, typically smaller investors as they assess the strength and nature of their commitment to a manager. With every new SMA, the compliance burden could become disproportionately heavier as the cocktail of governance provisions intended to contain potentially competing interests grows ever more complex.

"We are mindful of separate accounts because they can skew the traditional GP-LP dynamic. Understanding that dynamic is an important due diligence point for us," says Eric Marchand, an investment director with Unigestion. "If it's an evergreen-style account with a guaranteed check over and over, is the alignment the same as for normal LPs? It could lead to a two-tiered approach to how LPs are treated. These concerns would have to be legislated for in any agreement."

Viva variety

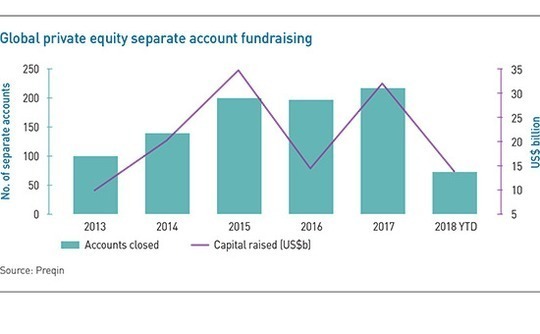

Bain & Company has classified SMAs as shadow capital because they exist outside the traditional fund structure and can have a distorting effect on investment. It estimated last year that SMAs comprise almost 6% of private capital raised, up from 2.5% in 2006. Meanwhile, Preqin found that a record 216 SMAs closed in 2017 – more than double the 2013 figure – with $31.8 billion in aggregate capital.

These datasets present a general picture rather than offering specific insights. No distinction is made as to whether the responding investors are interested in SMAs launched by GPs or fund-of-funds providers offering a combination of primary, secondary, and co-investment. Moreover, the variety of separate accounts is arguably more important than the overall number of them.

Two of the most famous SMAs involve Teacher Retirement System of Texas, which signed up KKR and Apollo Global Management in 2012 to manage assets across private equity, real assets and credit. A tactical opportunities vertical was added three years later. As of August 2017, the two programs had a combined net asset value of $5.1 billion, with commitments totaling $10 billion. The capital is said to be deployed across a range of funds, co-investments and other strategic initiatives, with the pension fund having some say over allocations and preferential treatment on fees.

At the other end of the spectrum, an Asia-based venture capital firm with a few hundred million dollars in assets under management (AUM) was recently approached about a SMA. The manager already offers co-investment in follow-on rounds and several of its larger LPs are interested in setting up a pre-approved pool of capital, so they don't have to go through their investment committees every time an opportunity arises.

Excluding global firms that have a presence in Asia, few GPs offer the scale and multi-strategy scope that lends itself to SMAs along the lines of Texas Teachers-style long-term strategic partnerships brokered at the CIO level. PAG, for example, has been running private equity, real estate and absolute returns businesses for longer than most. Some LPs are said to have made sizeable commitments to a couple of these strategies in the past, but they wrote separate checks.

"We have not seen a lot of examples with leading Asian sponsors. This is possibly because Asia is less mature as a PE market with fewer large multi-strategy sponsors," says Justin Dolling, a partner at Kirkland & Ellis. "At the same time, as pan-regional funds are getting larger, sponsors are more focused on increasing AUM within their main funds. If a sponsor is looking to double the size of its main fund, it won't necessarily have a lot of capacity or appetite for separate accounts."

As such, while fund formation lawyers claim to have seen an increase in SMAs in the region, most are essentially co-investment arrangements within a single strategy. Typically, an LP wants to tie in some co-investment to its fund allocation and the SMA guarantees that right at a time when GPs are wary about giving binding commitments in this area.

"What we often see in Asia is an account co-investing alongside an existing fund or with a slightly different strategy to the existing fund," says Gavin Anderson, a partner at Debevoise & Plimpton. "Sometimes people do a bit of juggling, it depends on how much capital you are managing and big your opportunities are. If you are doing a lot of larger deals, you are going to the market for co-invest in any case, so it's not that much of a stretch to have a handful of separate accounts alongside you. For a smaller manager, that would be overkill."

Special treatment

Even within this relatively constrained remit, there is room for customization – and it can work to the benefit of both sides. For the LP, fees and terms might be more attractive than those available in most co-mingled funds; they can demand bespoke reporting; they might enjoy greater flexibility regarding termination of the agreement and modification of the investment remit; and they are able to exert more control over the activities of the manager.

Private equity firms, meanwhile, see the merits of building alliances with large investors that could become important partners. A separate account brings in additional capital through which a GP can develop its track record and pursue larger deals in conjunction with their main funds. In addition, opportunities often gravitate to these LPs, which means they can become valuable sources of deal flow.

Indeed, these arrangements are sometimes favored by LPs with no direct involvement in them. "There are situations in which a large investor in a fund has preferential access to a sidecar on a no fee, no carry basis. I don't mind that. It's a sweetener for larger investors," says Unigestion's Marchand. "These sidecars also enable funds to stay at the same level as before but retain the ability to do large deals. There are many variants on that. It all comes down to how it is structured."

The optimal approach might be to allow every LP to participate in the sidecar, but this isn't always practical. For example, an investor's pro rata allocation to a deal might be too small to make it worthwhile, but once the GP has reallocated the equity, there is not enough time left for the remaining investors to take part in the deal. A more workable approach is to open the sidecar to LPs that put in above a certain amount or come into the first close on a fund. It reflects the reality that not all investors are the same and so they cannot expect equal treatment.

"Smaller LPs are always nervous that these guys are getting better terms. But a large LP will get a fee break anyway, whether it has a SMA or is an investor in the main fund. That should be clearly identified – a $10 million LP is not going to get the same terms as a $1 billion LP," says a partner with a global private equity firm. "They aren't going to get better carry than the other investors. It's more about the flexibility."

Standard practice at this firm is to allow a couple of separate accounts alongside each flagship fund. The partner identifies the three main motivating factors for LPs as confidentiality, securing terms without having them apply to other investors covered by a most favored nation (MFN) clause, and speed of deployment. On the latter point, some LPs ask that their capital be deployed over three years rather than five, which means they are given a larger percentage allocation to early deals.

The question for smaller investors considering a commitment to a GP's main fund is whether they are comfortable with any preexisting separate account arrangements. Opaqueness is the red flag. Inquiries as to the identities of the account holders and the economics of the accounts might be rebuffed by the manager, but they are generally obliged to disclose any information that would have a material impact on the main fund.

"There is always a line. Sometimes the GP pushes back and says the terms on the SMA won't affect the fund, so it doesn't have to disclose," says Lorna Chen, a partner at Shearman & Sterling. "But it is very important for lawyers in the due diligence process to assess potential risks. If there is a renminbi fund with an overlapping strategy, we ask what it does and whether it will compete for deals with the US dollar fund. In the same way, if there's a managed account, we ask who it's with, how long it lasts, and what it does."

Allocation issues

The key considerations around how a SMA functions concern the allocation of investment opportunities. An LP friendly provision would state that the main fund has first call on all applicable deals and other vehicles only get involved once its appetite is satisfied. A watered-down version might respect this core principle but allow for some flexibility in how the GP makes allocations to vehicles with overlapping mandates, perhaps to the point of complete discretion.

"Some GPs and a lot of separate account managers have moved away from a main fund concept," says Wen Tan, co-head of Asian private equity at Aberdeen Standard Investments. "A co-mingled vehicle becomes one of many pari passu vehicles. You have multiple mandates at any given time and whenever an investment opportunity arises you assess which mandates it fits into and then allocate between them. Best practice is for this to be under an objective formula rather than a subjective one."

A private equity firm might find itself in a more difficult position when seeking to establish a SMA after the fact. The separate account could be stopped in its tracks if there is sufficient overlap with an existing comingled fund such that the new vehicle is designated a successor fund, which can't be launched until a certain percentage of its predecessor has been deployed.

Meanwhile, tightly-worded existing provisions can be problematic in that they prevent senior executives from spending time on the SMA because doing so could trigger a key person event on an existing fund. Much the same applies to deal allocation. If the duty to offer is exclusive to the preexisting main fund, the GP might not have the flexibility to include another vehicle in deals that fit both mandates.

And then compliance doesn't necessarily eradicate suspicion. "Even if a GP is generally comfortable that it has discharged its duties to the main fund because it has taken its full allocation of any investment opportunity, potential conflicts of interest still exist where the GP is taking carry or other economics from the SMA," says Kirkland's Dolling. These concerns are exacerbated if performance of the fund lags that of the SMA. The GP would be incentivized to favor the SMA because there is a better chance of getting carried interest from it.

Most fund formation lawyers that spoke to AVCJ claim to have drawn managers' attention to areas where there is too much overlap for comfort. One solution is to try and preempt these obstacles by ensuring contract provisions are wide enough to accommodate future plans, but there is still likely to be pushback from LPs coming into those funds that want to ensure their interests remain aligned with those of the GP.

Despite these complications, SMAs appear to be gaining traction with a wider selection of managers in Asia. If separate accounts are inappropriate for most small firms and already part of the furniture for large-cap players, Cleary Gottlieb's Lee notes that many of the interesting developments are taking place in between these two poles. An increasing number of middle-market private equity firms are talking to investors about their options in terms of SMAs.

"The theoretical purity of one-mandate-at-a-time investing doesn't really exist now for part of the industry. That model has been chipped away by the multiple mandate approach," adds Aberdeen Standard's Tan. "This is a reality and there's no moving away from it."

SIDEBAR: The LP angle - NZ Super

New Zealand Superannuation Fund's (NZ Super) approach to investment underwent a fundamental change in 2010 with the introduction of a reference portfolio in place of a strategic asset allocation model. The reference portfolio sets a base allocation and specific investment opportunities - across different asset classes - are considered in terms of whether they can improve returns or reduce risk. Then the team figures out the best way to access these opportunities.

Separately managed accounts (SMAs) have come to play a significant role in this strategy largely because of the flexibility they allow. "It gives us control over the allocation of capital and risk. If we are invested in a fund, the capital could be locked up for as long as 10 years and over that period the investment environment might change in its attractiveness. We want to structure clauses that allow for greater flexibility," says Del Hart, head of external investments and partnerships at NZ Super.

This flexibility is manifested in the right to turn off capital calls on SMAs with as little as 90 days' notice. (With more liquid strategies, NZ Super can liquidate its position on a monthly basis compared to a quarterly basis for co-mingled funds). SMAs are also favored for the scope they give in negotiating fee discounts and bespoke reporting terms.

Another aspect of the transition to a reference portfolio was the pursuit of fewer, but deeper, GP relationships. NZ Super's minimum size for a SMA is typically $250 million. Due to the smaller scale of the New Zealand market, an exception was made for allocations to three domestic growth equity managers in 2016 via sidecar vehicles that offered more flexible terms.

These allocations were also exceptional in that NZ Super has steered clear of traditional global private equity in recent years due to its view on the attractiveness of this space relative to other available investment opportunities.

Hart admits that NZ Super's preference for flexible SMAs necessarily leads the group to larger managers that have sufficient recurring fee income that they can absorb the shock of a large commitment suddenly being turned off. Moreover, some GPs prefer not to work under such an arrangement.

"We have calls with the shortlisted managers to test whether they have the appetite and ability to offer us separate accounts, so it becomes part of the selection criteria," she adds. "There are some capable managers that have been successful raising successor funds and they have no appetite for separate accounts."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.