Korean project funds: Lines of sight

The prevalence of project funds in Korea is routinely linked to local institutional investors’ innate discomfort with blind pool vehicles. But is this dynamic holding back middle market managers?

Project funds – vehicles conceived to hold a single asset – are a fixture of the Korean private equity landscape. They account for the bulk of funds raised by the approximately 500 GPs registered with the country's securities regulator. ACE Equity Partners is one of them, and David Ko, who spent a decade with SkyLake Investment before establishing the firm last year, has no plans to change tack.

"If I have a good deal, it's no problem raising money through project funds. I was able to close four transactions within a year, entirely through project funds and mostly with repeat LPs. I'm working on three more, larger in size, that should close in the next couple of months," he says. "I don't like blind funds and there are no plans to raise one because we are doing well with project funds."

Ko is one of numerous Korean PE executives that have departed established firms and struck out on their own; he estimates that 100 new GPs, including spin-outs, have been formed in the last year, all of which are focusing on project funds. Unlike Ko, most are looking to build up track records with a view to raising traditional blind pool, or comingled, vehicles. It is unclear whether a relatively immature LP community is ready to support a young industry in making this jump.

Avoid the unknown

Asked to explain the rise in project fund activity in recent years, a Korea-based international LP offers three reasons: the emergence of a new generation of GPs, a relaxation in regulations that has made it easier to set up asset management firms, and the sheer volume of capital local institutional investors must put to work. "They have more money than they can deploy in the traditional market," he says. "There is a lot of pressure on teams to find ways to deploy their domestic allocations."

But the longer-standing and arguably more pervasive explanation is a wariness on the part of these investors to participate in blind pool funds. Real estate and infrastructure come more easily because capital can usually be deployed faster and starts coming back sooner in the form of yields.

Even when there is a willingness to back a local blind pool vehicle, the lifespan is shorter than normal. Korea's National Pension Service (NPS) has lengthened the time horizons on the fund tenders it issues from six to nine years, and once this behemoth agrees to anchor a fund the other investors must accept the same terms. But in the absence of NPS, other investors will routinely shave years off the total, according to industry sources.

Local private equity firms are also hampered in their efforts to raise blind pools because the industry is less than 15 years old, which means few have experienced the full fund cycle. "LPs, especially public, state-owned institutional investors, are reluctant to commit to funds with no track record," says Jong-Gun Seo, head of the investment division at Korea Growth Investment Corp, a domestic fund-of-funds. "New GPs are naturally forced to form the project funds to establish track records."

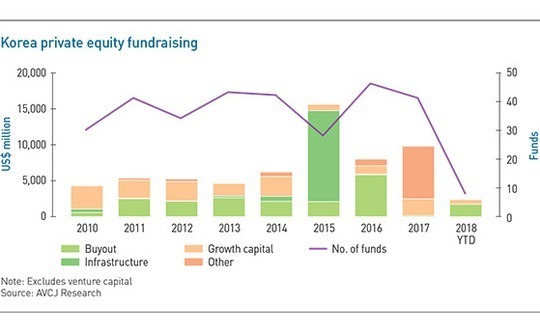

Several locally registered firms with international heritage or led by teams that have preexisting overseas LP relationships have managed to get traction with local investors beyond NPS. However, Jason Shin, a managing partner at VIG Partners, estimates that no more than 20 managers have succeeded in raising capital for comingled funds, excluding venture capital.

As a purely domestic firm, VIG was unusual in that it launched comingled funds from the outset. Shin credits his co-founder, Yangho Byeon, for winning over investors. Byeon, a career civil servant with the Ministry of Finance & Economy is known for being jailed – and then cleared – as part of a corruption investigation into the politically fraught sale of Korea Exchange Bank to Lone Star in 2003. But in 2005 he was synonymous with the country's post-global financial crisis restructuring efforts.

Financial institutions made up the entire corpus for Fund I, a consequence of both limited local LP activity in the market and strategic positioning. VIG, then known as Vogo Investment, had experience in financial services and made clear its plans to pursue deals in the sector. Similarly, SkyLake Investment, which was founded a year later by the ex-head of the Ministry of Information & Communication, raised blind pool capital from day one in part due to its tech-focused strategy.

New order

Other local GPs, such as JKL Partners and Crescendo Equity Partners, have since graduated from project to blind pool funds based on performance rather than founder credibility alone. Crescendo, which was seeded by PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel in 2012, took three years to close its first comingled fund with a modest corpus of KRW74 billion ($67 million). The firm recently consolidated its position in the middle market with a second fund of KRW450 billion, but the transition hasn't been easy.

"It's a whole new level in terms of what LPs require," says Kevin Lee, a founding partner at Crescendo. "They aren't just looking at a single deal, but at you: they conduct thorough due diligence on the GP itself, the team, its history, track record, and strategy. You must meet all these requirements to raise a blind pool fund. If you want to raise a project fund, the process is not as rigorous."

One of the more recent additions to the blind pool cohort is Glenwood Private Equity, which raised KRW453 billion for its debut fund on the back of two deals: consumer appliances manufacturer Tongyang Magic, acquired with NH Private Equity in 2014 and sold to SK Networks in 2016; and construction materials business Halla Cement, bought alongside Baring Private Equity Asia in 2016, with the stake exited to the pan-regional GP the following year.

This adds credence to an assertion that GPs are increasingly being fast-tracked into the comingled space, but these managers may have very different pedigrees based on the type of investments they have made and the characteristics of their project funds.

ACE Equity and Orchestra Private Equity – an advisory-turned-investment firm founded by Jay Kim, formerly of The Riverside Company and PineBridge Investment – differ from most in that they primarily focus on buyouts. "There are some other younger funds like us doing buyouts on a project fund basis, but probably no more than half a dozen," Kim adds. "Project funds in Korea tend to be for special situations investments and they feature convertible bonds, often with put options."

Ko claims six-plus-two years is the standard life for his project funds, while Orchestra's Kim cites five-plus-two years. Management fees and carried interest are 1-1.75% and 10-30%, respectively. The lower the level of expertise a deal requires, the shorter the fund life and the less appetizing the economics. Asked for a snapshot of the uncomfortable end of the spectrum, several industry participants suggested three years and a 0.5% management fee, but it depends on the target asset.

Convertible bonds or redeemable convertible preference share-based instruments serve as a downside protection mechanism for project funds, enabling them to opt out of equity exposure in minority deals. In buyout situations, project fund managers have been known to take minority equity positions alongside strategic partners but with a preferred waterfall-style structure, so they get paid out first when it comes to exit.

"These are mezzanine structures designed to deliver single-digit returns. The equity kicker on the convertible bond could take you into the high teens or a partner guarantees to cover a certain percentage return but takes most of the upside if it exceeds the threshold," says one local investor. "These LPs are IRR-driven rather than cash-on-cash driven. They are happy with quick flips that beat their 6-8% hurdle rate."

Help or hindrance?

Some managers have the project fund process down to a fine art. Having negotiated a deal with the seller, they package up the proposition and the due diligence materials in a way that makes it presentable to an LP investment committee. Downside protection and upside potential are obligatory. Initial contact might be made with a prospective anchor LP, with a view to making other participants term takers rather than setters. Letters of intent are collected and the deal closes.

Moreover, there is no shortage of interested participants. For example, Orchestra's second project fund, which financed the KRW61 billion acquisition of a majority stake in Seoul Vision, a post-production house for TV commercials, closed in less than four weeks earlier this year. It helped that real estate accounted for half the deal value, offering an attractive downside protection mechanism.

"These tend to be mid-tier LPs, like agricultural cooperatives, mid-size endowments, and foundations," says Kim. ACE Equity is seeing strong demand from financial institutions, but the common factor is that these investors have risk profiles that restrict the scope of their involvement or little experience of the asset class.

The broader question is whether these vehicles are helping or hindering the development of Korea's middle market. On one hand, an executive spinning out from an established firm with a couple of deals in his or her pocket can use project funds to deploy capital immediately and begin working towards a blind pool. On the other, they could be enabling a version of private equity – short holding periods, minority positions, limited value add – that does not deliver optimal returns.

A short fund life means a GP is under pressure to deploy capital quickly, and so they become less discerning in deal selection and then have limited time to try and realize value in what they do invest in. Some industry participants blame this dynamic for a lack of local GPs that are skilled in buyouts. The likes of Hahn & Co. and Anchor Equity Partners were founded by Korean executives who worked for foreign firms and they have yet to raise any capital from domestic LPs.

For the same reasons, project fund managers are likely to find it harder to win allocations from foreign investors. "When we see project funds in Korea, they are often new GPs that are just setting up and there's a deal they have been cooking for a while," says the Korea-based international LP. "Often these GPs don't have a really deep or proven skill set. Unless there is a strong strategic reason, it is hard to commit to a project fund."

All these issues should be viewed in the context of an industry that is barely 15 years old. "Maybe it is just a growing pain, a way for these guys to get more exposure and experience investing in private equity funds," says VIG's Shin. "There will be a few project fund guys who outperform others and they will get seeded and become bigger. It's an evolving process."

The near-term future of project funds is assured, simply because this evolution will be gradual. Industry participants claim they are seeing change at the margins of the LP universe: project fund tenures being lengthened; a recognition that blind pools should play more of a role in investment programs; and an expectation that greater exposure to offshore private equity will see international practices become ingrained in the domestic market.

The counter view is that deeper structural reforms are required so that CIOs are shaken free of the IRR-driven mindset. And even if there is greater sophistication at the top of the market, the volume of capital coming in at the bottom from smaller LPs that are new to alternatives would slow the overall pace of change.

But to some it is a case of when, not if. Steve Kim, CIO at LP advisory firm Castling Investment Group, likens the Korean market to a barbell, with plentiful activity in big buyouts at one end and venture capital at the other, but less happening in the middle. He believes the situation is fluid, though. "This market is moving all the time," Kim says. "If you asked me the same question in a couple of years, it's quite likely there will be more entrants in the middle market by then."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.