Autonomous vehicles: Driving ambition

Asia’s driverless car space has become an increasingly popular investment destination in recent years, but a number of significant challenges must be resolved for the sector to gain widespread social acceptance

"Move fast and break things," the former motto of Facebook, is often cited as a guiding principle for the technology industry as a whole. Earlier this year, however, the mantra took literal form in the most tragic way possible, when a self-driving car developed by Uber struck and killed a 47-year-old woman in Arizona who crossed the street in front of it.

While this was not the first fatal accident involving an autonomous vehicle, the crash alarmed many observers because it seemed to have no logical explanation. The victim had been clearly visible prior to the collision, but the car did not change direction, made no attempt to decelerate and failed even to notify the safety driver (who was later determined to have been looking away from the road at the time). Moreover, the incident occurred on a clear night, in an area otherwise free of traffic, a situation that should have presented the artificial intelligence (AI) driver with no challenge.

Uber's autonomous vehicle fleet has yet to reach wide deployment – the car involved in the Arizona crash was part of a nationwide program intended to gather data on real-world traffic situations to help the company improve the performance of its driving software. But the fact that it flunked such an obvious test suggested that the company hadn't put its millions of training miles to proper use.

"When you're running your data set, it's not the normal data that matters to you," says James Ieong, chairman and managing partner of China-focused Pagoda Investment. "It's outliers and emergencies that you're looking for. And you need that information, because you need to be very safe – if there's an accident where somebody dies, that could set back the industry for a very long time."

The Uber incident shows that despite the excitement with which many start-ups and their investors view the field of autonomous vehicles, there are still obstacles to widespread adoption both from a regulatory and a cultural perspective. In addition, the nascent stage of the industry means the various players have yet to agree on a single model for safety and performance.

Cautious start

Asia, where driverless vehicles offer relief to congested cities and regulatory bodies can often move more quickly than their Western counterparts, may prove to be key to establishing autonomous driving as a viable industry, and investors are working to develop the region's technology talent. But long-term success depends on the ability of stakeholders to make a convincing argument for the paradigm shift.

Autonomous cars have a long history in Asia – the first crude driverless vehicle, which used cameras and an analog computer to stay within lane markings, was developed in Japan in 1977. However, until recently most of the headlines in the industry were generated by companies in Silicon Valley, such as Google's Waymo project and Apple's electric car initiative.

By contrast, investment activity in Asia gives the impression of a region slow to jump on the bandwagon. According to AVCJ Research, in six of the last 10 years no more than two investments were recorded, and only two years saw three deals take place. However, more recently this trend has dramatically reversed, with 17 transactions in 2017 and 10 so far this year.

Of these deals, 20 involved Chinese companies, not counting the likes of JingChi, a start-up based in Silicon Valley and focused on developing technology for autonomous cars in China that received a $50 million investment from Qiming Venture partners last year. These China-focused investments reflect the country's growth in technical talent, as well as an expected move by consumers toward technology that can free up their time for leisure or business activities.

"I think we're at a point of transitioning into a smart car generation, where a car will be not simply a utility, but a moving space," says Jixun Foo, a managing director at GGV Capital, which participated in an extended Series B round for road sensor and mapping software developer Momenta last year alongside Pagoda and has also supported US-based driving system maker Drive.ai. "It will still be able to take you from point A to point B, but it also has other possibilities while you're in that space."

Autonomous cars have been increasingly viewed as fertile ground for investment because they incorporate so many different types of technology, including software, processors, sensors, and communication equipment, that no one company can monopolize the field. This means that there is no shortage of promising start-ups to which GPs can commit capital and help in their development.

The diversity of technology developers has also created a broad range of investors, with corporate venture investors joining VC firms in backing companies active in areas that are relevant to their underlying businesses. For example, Intel Capital, the captive VC arm of Intel Corporation, sees the AI and data processing needs of driverless cars as an attractive use-case for the computer chips made by its parent, while GM Ventures, for obvious reasons, focuses on the role that autonomous technology can play in its own product line.

"The greatest source of value that we can provide to GM, other investors, and our portfolio companies is to commercialize a start-up's technology with the intent to be their first customer," GM Ventures President Jon Lauckner said at the Intel Capital Global Summit earlier this year. "That means we only invest in start-ups that have technologies that we are likely to implement in our vehicles, our plants, or our operating businesses."

Strategic players have also become active supporters of start-ups in the space – in the case of Ascent Robotics, a Japanese start-up developing AI technology for driverless cars, the company has agreements with several domestic car manufacturers to provide its software to them by 2020. Mobileye, a developer of road avoidance technology based in Israel to which Sailing Capital committed $50 million in 2015, was acquired by Intel earlier this year.

However, despite investors' enthusiasm for the sector and these aggressive moves, the ultimate test of the driverless car will be with ordinary consumers and whether they trust their chances in a vehicle over which they have absolutely no control.

Consumer concerns

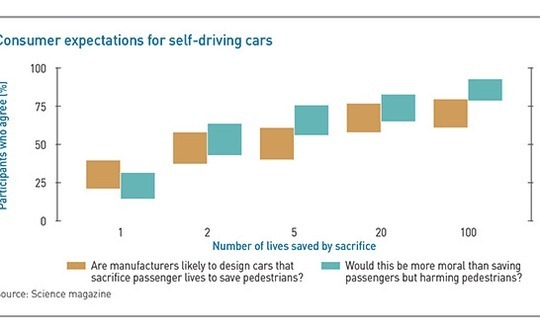

A survey of US consumers in 2016 provides some insight into the customer mindset. When asked whether autonomous vehicles should be programmed to sacrifice the lives of their occupants if it would mean avoiding a collision with innocent pedestrians, most agreed that this would be the moral thing to do as long as the number of pedestrians saved outnumbered those in the vehicle.

The number of participants who approved of sacrificing the passengers rose with the number of pedestrians at stake – though in almost all cases more participants approved of such a system than felt that car makers would actually implement it.

This pattern changed significantly when respondents were made to imagine their own lives in the equation – specifically, when asked if they would buy a car programmed to sacrifice its occupants, they preferred a vehicle that would save its passengers even if it meant killing pedestrians. In addition, more than 50% of respondents said they were more likely to buy a car that was not legally required to save others at the cost of its occupants' lives.

The study suggests that regulating autonomous vehicles could be a tricky proposition. If the majority of the population approves of a self-sacrificing model in principle, this could create pressure on regulators to require such behavior in all driverless cars. However, a consumer could be less likely to buy a vehicle that he feels will let him or his family die to save a stranger's life.

The question of whose safety a car is designed to prioritize is the main impetus behind the RSS model (responsibility, sensitivity, and safety), a project under development by Mobileye. The goal is to create a set of formal guidelines that define when a car is in danger, direct it to the appropriate response, and ensure that the car's systems are never directly responsible for an accident.

"I think without such a model, autonomous cars will remain a science project. It will never make it into mass production," says Amnon Shashua, CEO of Mobileye. "When there is an accident with an autonomous car, who's liable? It's not the passengers in the car, it's the supplier of the technology. And if there are tens of thousands of accidents those suppliers will go bankrupt very quickly."

This approach does create new questions – most notably whether a car programmed to avoid liability is as safe as one designed with the goal of preventing all deaths and injuries. Shashua believes that the advantage of the former is that it is achievable. While there is no way to guarantee that a car can avoid all accidents, a manufacturer can claim that its products will not be the cause of a mishap.

The RSS guidelines are also intended to be easy to implement across the industry, creating a uniform set of safety standards. Ideally, with all manufacturers operating from the same guidelines, all cars will generally behave the same way, and customers will gradually get a feel for how autonomous vehicles will react in any given situation.

However, all the safety standards in the world will not help if a car cannot analyze its surroundings properly. In the case of the Uber crash, sources close to the company's investigation have indicated that the victim was detected by the car, but that the control software incorrectly regarded the warning as a false positive and failed to react.

Even in this event, Uber's practices called for the safety driver in the vehicle to watch the road and stop the car in the event of a mishap. The company's cars are not intended to operate fully autonomously – currently they are limited to level three autonomy, in which drivers can take their hands off the wheel and feet off the pedals but are expected to pay attention at all times and retake control if needed.

The problem with this approach is that human drivers have a hard time telling the difference between level three and level four, in which vehicles are designed to perform all safety-critical driving functions and monitor roadway conditions for the entire trip. Safety drivers in level three cars have been observed to let their attention drift, and even to take their eyes off the road – as the Uber driver did.

Reaching level four and five, in which a vehicle's performance is equal or greater than that of a human driver across all environments, has proven to be the biggest challenge for the autonomous car industry. But some observers note that finding a solution through real-world training is inherently limited since it can only be carried out in certain locations such as Arizona and California, where the traffic regulators have given permission.

"Weather conditions are always beautiful in Arizona, streets are not congested, and the road is already determined," says Masayuki Ishizaki, CEO of Ascent. "Solutions developed for these areas are not going to scale, and especially won't be good enough for driving in a congested street and in most of the cities in Asia."

Asian angle

Ascent is developing a new way to train driverless car software that primarily uses simulated environments controlled by AI. The AI creates random scenarios to help the software build its experience level at a much faster pace than it could in real-world driving, while also keeping pedestrians safe.

The company sees Asia, and Japan in particular, as an ideal location for it to develop its software. The proximity to Japanese auto makers is one reason, but Ishizaki also feels that the lower cost of living compared to Silicon Valley allows it to attract skilled employees from all over the world, while its Japanese clients' high expectations for quality mean that the company can be confident its products will be accepted worldwide.

While Japan is known for its openness to technological change, industry professionals are confident that autonomous cars will gain acceptance in Asia as a whole, provided they can be adapted to the unique characteristics of each market's driving culture. Based on the rapid adoption of smart phones in the region, Asian consumers are viewed as open to considering new approaches to old problems and sufficiently unbound by traditional thinking.

"I think we may see this tech adopted more quickly in Asia, because there's less systemic baggage here to limit the growth trajectory of what's possible," says GGV's Foo. "For example, people argue that facial recognition is an invasion of privacy, but what that shows is that there can be faster innovation and development in a somewhat chaotic environment."

SIDEBAR: Autonomous flight - Watching the skies

Traffic congestion in Asian cities has prompted a number of solutions, from traditional public transport to newer approaches like automated taxis. Now a handful of VC-backed start-ups, among them US-based Joby Aviation and Germany-founded Volocopter, hope to literally leapfrog the competition by taking to the air.

Both companies have received significant venture backing – Joby raised a $200 million Series B round earlier this year from a group of investors including Singapore's EDBI and Intel Capital, while Volocopter has been backed by Intel Capital and Daimler. EDBI, the investment arm of Singapore's Economic Development Board, believed Joby offered an exciting vision

"With a growing population and more than one million vehicles on the roads, the challenge lies in optimizing the use of our limited space for more efficient, safe, and reliable transportation," says a spokesperson for EDBI. "Joby's aircraft can help augment existing local transportation to deliver safe, efficient and cost-free travel that can help move Singapore toward a car-light vision."

Joby and Volocopter's products resemble nothing so much as helicopters crossed with drones, with a mass of rotors surrounding a central pod for a pilot and passenger. The unusual design is dictated by the need to keep sound levels and therefore rotor speed as low as possible in urban environments. Multiple rotors also provide safety – Volocopter's vehicle can reach its destination with as many as six rotors out of service.

The company envisions fleets of the all-electric flying taxis conveying passengers to predetermined landing points. While the vehicles currently include a joystick and control panel, the plan is for them eventually to operate fully autonomously. Florian Reuter, CEO of Volocopter, says that this is the biggest hurdle after proving the helicopter's flightworthiness, since most autonomous driving software is intended for cars.

"In general, we're tapping into the same technological universe, but we have specific requirements – primarily the 3D aspect of it," says Reuter. "Many things in cars use the ground as a reference, and we don't have that when flying. So we really need to think about what's the technology logic behind it, and whether it will work in the third dimension."

Because the vehicle and the idea of autonomous operation are so unusual, Volocopter sees maintaining positive relationships with civil aviation authorities as of paramount importance. The company is currently flying test routes in Dubai and is negotiating with Singapore's regulators to do the same.

"No matter where we look, whether it's EASA [European Aviation Safety Agency] in Europe, FAA [Federal Aviation Administration] in the US, or any other jurisdiction, they are very open to talk with us and try to understand what they are dealing with," Reuter says. "But the level of implementation of modern rules really differs from jurisdiction to jurisdiction – while EASA's really cooperative, for example, they will never be as quick as Dubai or Singapore."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.