Australian superannuation reform: Efficiency drive

With proposed changes to Australia’s superannuation system emphasizing performance rather than just cost, more money could be directed into expensive yet high-performing asset classes like private equity

Hostplus, the A$24.7 billion ($18.2 billion) industry superannuation fund responsible for hospitality, tourism and recreation, was last week named Australia's number one MySuper plan, having delivered a net return of 12.5% for the 2018 financial year. The fund's leadership identified two key reasons for this strong performance: size and long-term outlook.

"The not-for-profit super sector has a long history of pooling long-term assets to achieve greater scale and long-term investment returns," CIO Sam Sicilia observed. Meanwhile, CEO David Ella highlighted the contributions made by positions in unlisted infrastructure and property as well as a shift towards niche or bespoke investments in private equity.

Industry superannuation funds, which differ from retail funds in that they are run solely to benefit members, dominate the SuperRatings rankings based on one-year and 10-year returns. Exposure to unlisted assets is certainly not the only driving factor, but it is a significant one.

The Productivity Commission, which recently published a draft report on the superannuation system, came to a similar conclusion. It developed two benchmark portfolios: one to replicate the generally higher unlisted assets allocations of industry funds; and another, with a lower target return, that was listed equities-heavy in order to mimic the traditional retail fund approach. Industry funds beat their benchmark return over a 20-year period, while retail funds fell below theirs.

The report is significant in that it assesses the need for reform to deliver greater efficiencies in the management of Australia's A$2.6 trillion in retirement savings, the fourth-largest such pool in the world. Although it is unlikely to have an immediate impact on asset allocation, the proposals point to meaningful change in the system – and the emphasis on performance, rather than just cost, is encouraging for those in relatively expensive asset classes like PE.

"There is clear understanding that the goal is net returns, not low fees for the sake of low fees," says Geoff Sanders, a partner at law firm Allens. "Hopefully this has put to rest concerns about a race to the bottom in terms of fees."

Further reform

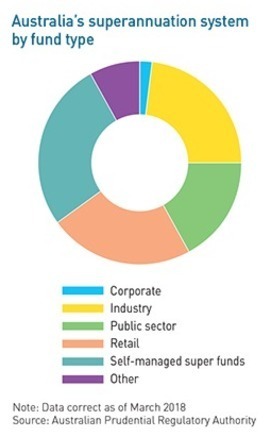

The MySuper reforms of 2011 delivered a class of easily comparable products with a competitive focus on net costs and returns. They account for 38% of the A$1.7 trillion held in funds regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA). Cost remains a concern – the commission observes that fees remain a drain on net returns, despite trending down in recent years – but now attention is also being paid to structural flaws that create a wide dispersion in fund performance.

One of the report's key findings is that the system is failing members who are defaulted into MySuper funds chosen by their employers because they do not exercise their right to choose a superannuation provider on starting a new job. A full-time worker in median underperforming MySuper product would retire with a balance 36% lower than if they were in a median top-10 fund.

If all products delivered returns in line with the top performers – and there were no unintended multiple accounts, which are often the result of people changing jobs and being re-defaulted into products – members would collectively be A$3.9 billion better off each year.

The shortlist – subject to renewal every four years – would comprise up to 10 superannuation products selected by an independent expert panel according to a clear set of criteria. Members who fail to make a choice within 60 days would be defaulted into one of the 10 products, via sequential allocation.

This is a draft proposal, so many practical issues are not fully resolved. It is unclear, for instance, how the independent panel would be selected and what selection criteria would be used. Moreover, the government might not accept the model as it stands in the report or the recommendations could be impacted by the ongoing royal commission into financial services, which includes superannuation.

Even if there were wholehearted support, the legislation might not make it through parliament in time. Australia will have a federal election next year, and should this result in a change in government, reform could move in another direction.

But the commission's report is still being taken seriously as an independent perspective on the future of superannuation. And if a version of the shortlist proposal were to be enacted, the implications for those that fail to make the cut could be dire indeed. "There are a couple of hundred MySuper funds with products for default money. It would be very hard to survive for four years if you have no default money coming in," says Nathan Hodge, a partner at King & Wood Mallesons.

Scale proposition

The expectation is that industry funds would be well represented in the shortlist, given their track record of performance. Allens' Sanders sees it as an endorsement of their approach and "probably good in the long term for private market managers, whether it's private equity, infrastructure, or real estate."

There is also a belief in some quarters that reforms could lead to rising alternatives allocations across the board if the government achieves its broader goal of boosting member engagement with the superannuation system, particularly in the younger demographics. Anyone who is willing to consider how his or her savings are invested – as opposed to being allocated into a default product – might decide their needs are suited to a more aggressive approach.

"If we were to make significant progress on engagement, I think it would alter the appetite of pension funds for different strategies," says Yasser El-Ansary, CEO of the Australian Private Equity & Venture Capital Association (AVCAL). "Once individual members of pension funds are actively involved in selecting their investment strategy and voting with their feet, I think we could see many of the pension funds allocate larger amounts of capital into strategies such as private equity."

One reason industry funds have greater exposure to unlisted assets than retail funds is that the latter are usually attached to large financial institutions that have their own, predominantly liquids-focused, managers. Another reason is size. As Hostplus observed, industry funds have larger pools of capital at their disposal, which means they can be more flexible and long-term in outlook.

In allowing the bulk of new money to flow into a concentrated group of funds, the shortlist system would inevitably allow the big to get bigger. "There will be winners in that top 10 list and there will be losers who have less money coming in and are subject to greater scrutiny from regulators as to why they are a standalone fund," says Sanders. "There will be fewer, larger funds, but it will take 5-10 years for this to work through the system."

Consolidation in the superannuation space has been on the agenda for some time, although about half of all funds overseen by APRA have less than A$1 billion in assets. The government wants to increase the pressure on smaller funds to fold into larger counterparts, and the shortlist system should support this effort. There is a similar rationale behind expanding the scale test currently used to assess MySuper products.

The plan is to establish an outcomes test that requires trustees to determine annually, in writing, whether the financial interests of members are being promoted "on a basis that goes beyond the number of beneficiaries or the amount of assets in the fund." The commission's report adds that the results should be independently verified every three years. Funds that fail to meet the conditions or underperform their benchmark for five or more years would be stripped of their MySuper status.

It is also proposed that trustees be required to disclose any attempt at a merger to APRA and explain why any failures to strike a deal were in the best interests of members.

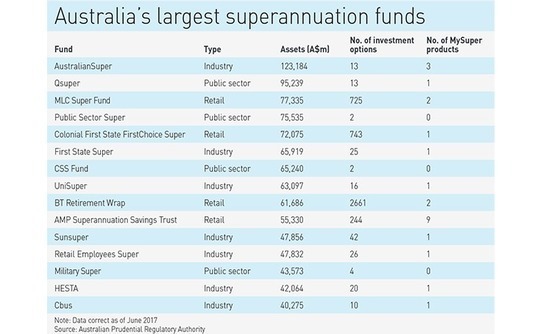

"Assuming APRA gets more active in enforcing the scale test, I would expect it to become more influential in encouraging small funds that are underperforming to merge," says Kristian Fok, CIO of Cbus, an industry fund. "The challenge is what do you bring as a merger partner. If a fund brings some new capability it can be strategically beneficial to your business. If it's a small fund in a declining industry and cash flow negative, it is harder to find entities interested in a merger."

Going direct?

While private markets managers might be expected to benefit from the emergence of larger industry funds that like unlisted exposure, it remains to be seen what impact increasing size has on the insourcing of operations. Cbus is an example of a player trying to use scale to its advantage. The $40 billion fund wants to bring more of its domestic coverage in-house, having reasoned that it cannot keep adding managers to accommodate net cash inflows of A$2 billion a year.

Cbus already has direct real estate exposure through its own property management business and it is in the process of hiring additional people to do the same in infrastructure and private debt. Private equity, however, is less of a priority because Cbus believes there is more value in building up its infrastructure capabilities.

This corresponds to the view of AVCAL's El-Ansary that an increase in super fund size doesn't signal a wholesale movement of investment in-house. While these larger players will explore new ways of deploying capital and accumulate expertise, this goes hand-in-hand with a greater appreciation of the challenges involved in executing private markets strategies. This may result in enhanced levels of co-investment and syndication, not necessarily more direct investment.

"I speak to many LPs here in this market who are clear on their appetite for a more dynamic and evolutionary approach to PE investment, and as part of that they want to see a change in the way they engage with their GP base on both fees and structure and performance reward," El-Ansary says. "But there is nothing in front of us to indicate that PE managers will be on the endangered species list anytime soon."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.