Outsourced CIO: Secret sauce

Teams spinning out from US endowments are competing in an increasingly competitive market for outsourced investment mandates from institutions. Scale and differentiation are the key selling points

David Swensen, the Yale University CIO credited with revolutionizing the endowment business model, has identified two primary reasons for his program's robust returns: asset allocation and manager selection. In 2013, he put a number on it. Over a 20-year period, Yale had outperformed the median endowment return by 5.1 percentage points – of that, 40% was attributed to knowing how much money to put in each asset class, and 60% to picking managers that could add value.

Swensen's 20-year return, which stood at 12.1% as of June 2017, is based on pursuing portfolio diversification and taking on more illiquidity risk. Half of Yale's assets are in PE, VC, real estate, and natural resources. This allocation is easy enough to copy but the return is far harder to emulate, especially given the dispersion between top and bottom quartile managers.

Various teams have spun out from endowments in the last 10 years and set up as independents, claiming they can bridge that gap. They are specialists in an OCIO (outsourced chief investment office) market that has become crowded as asset managers of all kinds seek to leverage the growing receptiveness of institutional investors to using hired help. But can the endowment secret sauce really be bottled and sold to the mass market?

"It's all in the execution, application and intelligent innovation. The roadmap is not the secret sauce. Even if you knew every manager on Yale's list you probably couldn't get into most of them. And then finding the next batch of great managers is ongoing – these aren't static portfolios – so you need the talent and resources to do that," says Dave Burke, CEO of Makena Capital Management, which was formed by a team from the Stanford University endowment.

There is one other advantage that Burke sees as equally significant: scale. Makena was founded in 2005 and has $19.5 billion in assets under management (AUM) in a relatively mature, cash-generative multi-asset portfolio. Burke says it would take market entrants a decade to reach a size where they have meaningful exposure to leading existing managers and can write big enough checks to be appealing to new GPs.

Size matters

This analysis is specific to endowment-style OCIO, but scale is one of several themes that resonates across the industry. The reality is a great many asset owners are subscale – which generally means having an AUM of less than $1 billion – and don't have the resources to build in-house teams capable of managing sophisticated investment portfolios. Some also carry the scars of poor past performance.

"Legacy portfolios have had huge amounts of exposure to the macroeconomic cycle because they invested largely in equity markets. Over the last 10-20 years, there's been a realization that they are too exposed to these risks and perhaps their investment experience has been more volatile than they would have liked," says Paul Colwell, head of the Asia advisory portfolio group at Willis Towers Watson (WTW). "There is a preference for a better investment profile and a smoother journey."

Outsourcing to a group that aggregates the portfolios of multiple investors creates the possibility of exposure to a wider variety of asset classes as well as bring down costs. In this context, the typical small university model of "a treasurer's office with one person who spends half their time on investments and an investment committee that meets once a quarter and is staffed by alumni who may not know about investment," is no longer viable, one former endowment employee observes.

While outsourcing by endowments has contributed to the expansion of the 15-fold expansion in the global OCIO market in the last decade, the substantial movers in the US in recent years have been corporates, which are outsourcing pension plans because they aren't core activities. The UK is going through the same transition. A 2017 KPMG survey found the number of fully outsourced defined benefit pension plans had risen to 546, up from 28 in 2007; they now account for 17% of the market.

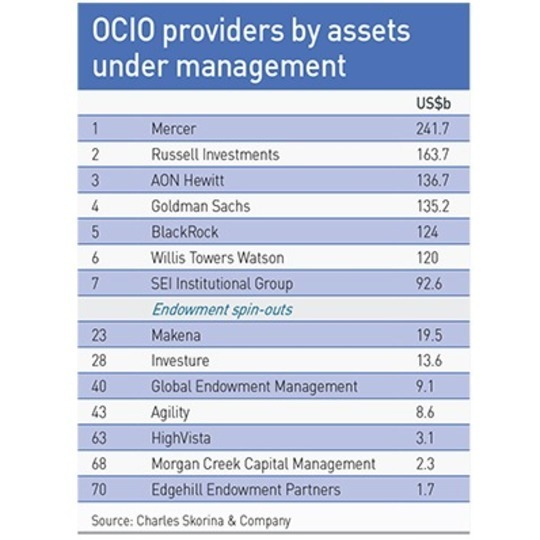

Charles Skorina, a US-based headhunter who specializes in placing CIOs and senior investment officers, argues that it is difficult for an endowment OCIO to get traction in the current climate. "Virtually all endowments and foundations with over $1 billion in AUM have internal managers and most that would outsource have already done so," he says. Meanwhile, US corporate pensions have little appetite for alternatives and tend to outsource to mainstream asset managers.

Skorina sees Edgehill Endowment Partners as a case in point. Established by the former CIO of Carnegie Corporation and the ex-deputy CIO of TIFF Investment Management, the firm recently secured a $1 billion mandate, but it has taken six years to reach an AUM of $1.7 billion. Mercer, Russell Investments, AON Hewitt, and WTW manage $662 billion between them, accounting for one third of the $1.9 trillion held by 80 OCIO providers that Skorina tracks.

Asked whether it's possible to bottle the endowment secret sauce, Skorina says yes but it's hard to attract clients and entry into the space would only be possible for a select few. Erick Odmark, a consultant who advises institutions on how to manage their investment programs, also answers in the affirmative, although his caveat is "the flavor might not be as good."

This refocuses the debate on whether these OCIO providers can deliver endowment-style exposure. Odmark's due diligence would address factors such as track record, fees, and potential conflicts of interest, but the onus is on the size and quality of the team. Edgehill is set up to work with a limited number of clients and is resourced accordingly. Makena is a bigger beast, but its clients still expect to get a diversified global portfolio that delivers strong returns over extended periods of time.

It should come as little surprise that the firm's investor base is split roughly equally between sovereign wealth funds and large pensions, family offices, and endowments and foundations. And only one third – principally endowments and foundations – fully outsource to Makena. The rest use the firm to top-up their existing programs.

Investors also gravitate to CA Capital Management, Cambridge Associates' OCIO business, in the knowledge that the firm has longstanding expertise in the alternatives space. While most clients outsource their entire program, a significant number of large institutions like pension funds and family offices seek a partial OCIO solution.

Custom fit

Broadly speaking, there are three open architecture OCIO models: comingled pools that offer uniform exposure to multiple asset classes; asset class-specific pools that are comingled but can be used as the building blocks for a portfolio that reflects individual risk-return objectives as well as legacy exposure; and portfolios that are fully customized on behalf of each client.

Makena has a flagship evergreen fund that is intended to function much like a diversified endowment portfolio and then single asset class vehicles for private equity and venture capital, real estate, natural resources, and hedge funds. Meanwhile, Investure, which was set up by the former CIO of the University of Virginia endowment, has $13.6 billion in AUM divided into a dozen portfolios, each one customized for a different endowment or foundation.

CA Capital is much the same but – with nearly $30 billion in AUM – on a larger scale, leveraging its global research platform. "We don't offer comingled pools or model portfolios, we invest each portfolio in a customized way. Clearly, there are better economics for a firm that does have a model portfolio or a pooled vehicle, but we don't think that is the best approach to investing for institutions that might have very different underlying needs," says Margaret Chen, the head of CA Capital.

These needs can vary enormously by size, remit, and geography. Makena has more than 200 client relationships, but the 10 largest account for 60% of AUM. While these groups aren't necessarily outsourcing their entire investment programs, they receive a highly bespoke service. This includes embedding professionals with Makena for months at a time to study the endowment model.

"CEOs and CIOs like to sit around a table with us and some of their peers, hear what everyone is doing, and discuss ways in which they can collaborate. They can benchmark their own assets classes against what they are seeing in ours," Burke adds. "And they love to hear deal flow ideas, manager ideas. We might work on something and there's room for a few other investors or they will tell us about a smaller manager who isn't going to get on a plane and come see us."

The firm's sovereign wealth fund clients are likely to fall into this category. Singapore's GIC Private is said to be a Makena client, while QIC – an investment manager controlled by the Queensland government that also manages third-party money – has in the past committed capital to Makena and Global Endowment Management (GEM). GEM was set up by the former CIOs of the Duke University and University of Florida endowments.

In each case, the OCIO relationship could be seen to complement well-established global private markets programs. Notably, they offer exposure to US venture capital, enabling the clients to establish relationships with hard-to-access managers – ultimately with a view to investing directly – or participate in funds that are below their minimum check size threshold. Australia's Future Fund took a similar approach, using Greenspring Associates as its partner in building a US VC portfolio.

Out of Asia

GIC, QIC and Future Fund are among the most sophisticated institutional investors in Asia, so their strategies are not indicative of LP behavior across the region. However, the notion of outsourcing a single asset class, or even just a geographical portion of that asset class, has gained traction. Fund-of-funds and separately managed accounts in the alternatives space are a good example.

"In Asia, my impression is they are most interested in specialized mandates," observes CA Capital's Chen. "They also see OCIO slightly differently to the US in that Asia is more comfortable with the fund-of-funds approach, although that is changing over time."

Plotting a developmental trajectory is difficult in markets, particularly Asia ex-Japan and Australia, where OCIO is still in its nascent stages. There is a clutch of very large institutions that might opt to manage everything in-house, perhaps issuing some advisory mandates, or outsource certain segments because they are accumulating assets so quickly and under pressure to deploy. Most OCIO providers have tried to engage government-linked asset owners on a strategic basis.

Beyond that, industry participants see potential in different areas. CA is reasonably bullish about the prospects for endowments and foundations in Asia, citing a correlation between the amount of interest and the creation of charitable institutions in the region. High net worth individuals and family offices are another target group. WTW, meanwhile, doesn't spend much time with family offices, preferring to focus on endowments, sovereign wealth funds, and pensions.

WTW's Colwell draws parallels with the evolution of OCIO in the UK. Outsourcing initially focused on segments of the portfolio that were difficult to manage and gradually encompassed entire programs, driven in part by a recognition that the collective approach was the best way to manage risk. While he acknowledges it will take time for Asia to move in the same direction, there are signs of consolidation in private markets.

"Unless you are talking about very large players, it tends to be more global than regional in terms of the mandate," Colwell says. "Rather than just PE, it might be private markets – which includes real estate, infrastructure and possibly private debt and natural resources – because they want a cross-asset investment portfolio that can take advantage of the opportunities that arise across the space."

Discussions are ongoing in markets like Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and Korea as asset owners become increasingly aware of what their peers are doing in other geographies and consider the implications for their own portfolios in terms of scope, scale, fees, and risk-managed investment performance. Two-thirds of Makena's capital comes from outside the US, including clients in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Australia. Burke admits to being surprised by the uptake.

"We thought it would be small US-based foundations and endowments that need the same results as Stanford but are subscale and cannot afford any people or can only afford a consultant and they will never be an important client for that consultant," he says. "That group showed up, but so did others from around the world."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.