Japan robotics: Friendly faces

Japan’s home robotics industry is still in its early stages, and considerable work is required to create devices that can both appeal to everyday consumers and meaningfully contribute to their lives

Robotic servants have long been staples of science fiction, representing the possibilities of technological progress for making life easier. But the concept has proven difficult to translate into reality. Even in Japan, where the idea would seem an easy sell due to the country's long cultural affinity with robots, developers have struggled to marry their technological innovations to mass-market appeal.

"I've been to various home robot competitions where devices designed like the Terminator were doing chores," remembers Kensei Demura, robotics teacher and founder of personal robot developer DKT. "This was crazy to me, because children would get scared. Home robot design can't be the Terminator or Gundam style; we need to make a robot that's cuter in order to be accepted in Japan."

Aesthetic appeal is the most obvious challenge for entrepreneurs trying to leverage Japan's leadership in industrial robotics in a domestic setting, but industry insiders say creating an attractive robot is likely far easier than finding something for it to do. Even high-profile humanoid robot projects like Pepper and Asimo have yet to make a compelling case for themselves beyond the novelty factor.

While there is an active home robotics development community in Japan, in the absence of a killer app many perceive the industry to be limited to enthusiasts pursuing passion projects rather than serious entrepreneurs. As a result, personal robotics start-ups have struggled to gain traction, with VC investors reluctant to commit capital to companies without a clear near-term path to monetization. This is likely to remain the case until the industry has some success stories.

"For all the hype about robotics and all the inquiries I get from journalists about it, there are surprisingly few robotics start-ups in Japan. I see maybe one a month, if that. Out of 35 companies we've invested in since launching our fund, only two are involved in robotics," says James Riney, head of 500 Startups Japan.

Data from AVCJ Research bear this observation out: of nearly 160 investments in robotics-related start-ups across Asia over the past 10 years, only 35 were in Japanese companies, and Japanese start-ups accounted for $206 million from the total of $1.1 billion invested across the region overall. By contrast, 62 investments were recorded for start-ups in mainland China, with $582 million invested overall, while India saw 31 investments for a total of $252 million.

Moreover, only six of the deals in Japan involved commitments of $5 million or above – the same as India – while 22 investments in China were for at least $5 million. No investments were recorded in Japanese robotics start-ups prior to 2014.

Unmet needs

The data suggest an industry still in its youth, but robotics has a long history in Japan. For decades, the country has led the world in the development of industrial robotics, and a casual observer might expect the technological expertise from this area to transfer easily into home applications. However, in practice it can be difficult to adapt equipment designed for one customer base to serve a different market.

In the case of Laundroid, a laundry-folding robot developed by the start-up Seven Dreamers, the company had to design the three robot manipulators in the device from scratch, because existing technology would be unacceptable from the standpoint of price, safety and appearance.

"A factory can have robot arms out in the open, or perhaps in a cage for safety. But to handle clothing our robot arms needed to be very strong, and that can pose a danger for pets or children," says Shin Sakane, founder of Seven Dreamers. "So from the beginning we had to keep all the robot arms in a box, like a piece of furniture or a home appliance."

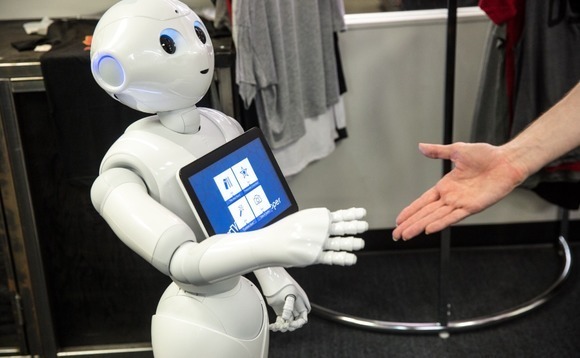

This last group provides another application for robots in the form of companionship. Pepper, designed by SoftBank subsidiary Aldebaran Robotics, is the most well-known example of a robot intended to create a social bond with human users: with its large eyes, smiling mouth and relaxed posture, the device is almost the opposite of the threatening mechanical men in decades of science fiction movies.

Japanese culture is in some ways uniquely suited to foster an appreciation of humanoid robots. The country has a long history of friendly robots in movies and TV, and DKT's Demura recalls hearing discussions of long-running series such as Doraemon and Gundam between robotics engineers ranging from 20 to 50 years old.

"Doraemon and the Terminator are both robots sent back from the future, but one is sent to help while the other is sent to kill. These portrayals play an important role in shaping perception of new technologies," says 500 Startups' Riney. "That's probably why robots in Japan tend to be humanoid. Alexa is more useful than Pepper, but it also looks like HAL from 2001."

Utility for end users is where Pepper and many other humanoid robots fall short compared with more specialized designs. Pepper has found popularity as an automated shop attendant, and SoftBank touts its flexibility in that users can create their own applications. But many developers feel the manufacturer's emphasis on aesthetic appeal has resulted in compromises. For example, Pepper's arms and hands have difficulty even in picking up small objects. The robot can gesture while it talks, but helping with chores is another matter.

The golden mean

The ideal that many robot developers are pursuing is a device that combines the relatability of Pepper with the utility of more specialized hardware. However, this requires both hardware and software expertise, the latter of which is difficult to find in Japan.

In the case of Laundroid, for example, Seven Dreamers found recruiting engineers to be relatively easy. The real challenge was building a team to write software to help the robot recognize what type of clothes it was handling and fold them without damaging the items.

Laundroid's long development history – Sakane first conceived of the robot in 2005 and is currently planning to launch it next Spring – suggests the deep commitment of time and capital required to make a viable home robot. Even a device that does only one job can take over a decade to bring to market, and after its launch it still needs to find a user base.

Naturally, VC investors are reluctant to commit to companies with such an uncertain payoff. The bulk of Seven Dreamers' support has come from partnerships with appliance maker Panasonic and home builder Daiwa House. Investment in the industry largely remains limited to early-stage rounds for companies like Connected Robotics, a cooking robot backed by 500 Startups.

One of the few exceptions is Groove X, a company founded by the development leader of Pepper that is currently developing an empathetic robot called Lovot. Innovation Network Corporation of Japan (INCJ) and Mirai Creation Investment, a fund operated by Sparx Group, invested JPY6.4 billion ($57 million) in Groove X last year.

"I think the big challenge for a service robot is, what's its purpose? It's cute, it's cool, and it's fun to interact with, but if it's really going to be capable, it's probably going to be expensive enough that you can't sell a lot just based on the fact that it's cool," says Brian Gerkey, CEO of Open Robotics, a US-based developer of open-source robotics software. "It should have some really useful function, and that is the thing that people haven't quite cracked yet."

Opportunities for home robotics may improve given time, as Japanese developers can build on others' achievements. For example, DKT's educational robot Happymini runs on the Robotic Operating System (ROS), developed by Open Robotics to give robot developers a universal platform that can handle common tasks on multiple hardware configurations.

Industry observers expect the availability of universal tools like ROS to ease the burden on Japanese start-ups of writing their own software. Entrepreneurs instead can focus on the concepts that set them apart from their competitors and create unique robotics platforms.

"The potential market is so huge that we don't think of it as winner take all," says Shunichi Ozasa, a spokesperson for Sparx. "Like automobiles or watches, we expect many kinds of robots to appear for consumers to choose from. In that sense, there is still a lot of room for smaller developers to enter the market."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.