Portfolio: Allegro Funds and Carpet Court

Carpet Court’s attractive growth plan was held back by its structural weaknesses. Under the ownership of Allegro Funds, the company has new focus as the leader in New Zealand’s fragmented flooring industry

Allegro Funds is used to looking for problems to solve in its portfolio companies. When approached in 2013 by Carpet Court, a troubled New Zealand flooring retailer looking for an acquirer, it was ready for the challenge. But negotiations hit a snag when Flooring Brands, which owned the company at the time, claimed its assessment was too negative.

"We took a quick look under the hood and saw that the business was pretty broken and needed a tremendous amount of work to build on its foundation and get to a level of operational excellence," says Fay Bou, an investment director at Allegro. "That difference of opinion with the vendor, who thought it was a well-performing business, meant that we couldn't agree on value. Two years later we turned out to be right."

A second chance came in 2015 when, after years of sluggish growth by Carpet Court, Flooring Brands' bank Westpac lost patience with the company and mandated a sale. The circumstances meant that not only did Allegro have more leverage to insist on its preferred valuation, but the additional two years meant the shortcomings of the owners' original business plan were in even sharper relief.

As a result, the GP had scope to implement the changes that it wanted, principally removing the mental roadblocks that stood in the way of Carpet Court's success in the fragmented New Zealand flooring industry. Three years on, Allegro is looking to pivot to new opportunities in the broader home improvement market, along with improving the company's business with corporate customers. There is an overriding sense that confidence has been restored and Carpet Court has the momentum to carry these plans to a successful conclusion.

Poor execution

While Allegro disagreed with some of Flooring Brand's assumptions about Carpet Court, the firm saw the company above all as a failure of execution. In fact, Allegro concluded that Carpet Court's business plan was fundamentally sound: the brand had sought since its inception in 2005 to become New Zealand's only nationwide chain of flooring sellers and service providers.

This was an enticing proposition in a market dominated by independent operators with one or two outlets. Furthermore, big-box retailers like Mitre 10 and Bunnings had shown little interest in flooring. Carpet Court's owners planned to buy these smaller operators and build a strong domestic platform, and when it approached Allegro in 2013 it had acquired 60 stores. But the management had fallen short in the critical work of streamlining operations across its network.

"While we think that's a good thesis in a fragmented cottage industry, they did very little if anything in terms of integrating those operators into a broader platform that was sustainable," says Bou. "In fact, they'd left each operator largely independent of the core, and that's problematic when you're trying to build a scale operator."

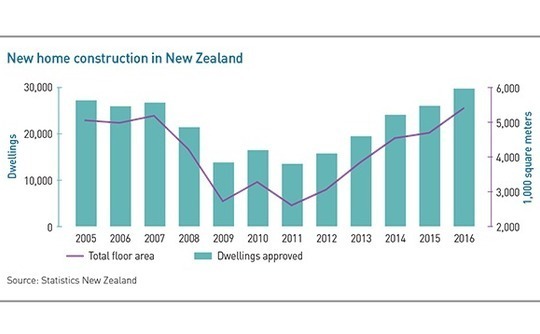

Allegro pointed out in 2013 that inefficiencies created by this oversight had limited the company's growth in critical ways, but the owners pushed back against this assessment. Rather, Flooring Brands blamed sluggish growth on the long-term slump in the overall housing market: approvals for new housing construction had fallen in six of the eight years since Carpet Court's founding, reaching a 30-year low of about 13,500 in 2011 and recovering only slightly as of 2012. Creditors were duly convinced that Carpet Court's business would pick up as activity returned on the construction side.

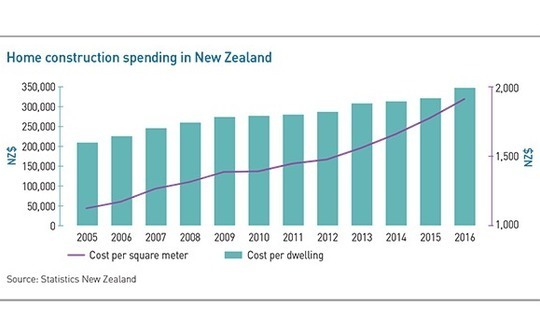

Two years on, New Zealand's housing industry was booming: construction approvals reached 24,000 in 2014 with a total floor area of 4.5 million square meters. Spending on home construction had also resumed its growth after nearly stagnating from 2009-2010. Average cost per dwelling reached NZ$312,000 ($225,000) in 2014 and cost per square meter grew to NZ$1,655.

In its reassessment of Carpet Court in 2015, Allegro found that the problems it had identified two years earlier were still present. At the root was a failure to understand the effort required to build a real nationwide retail chain. The company had made dozens of acquisitions, but management had done little work to organize the stores into a unified platform.

Correcting this deficiency would require overhauling the company's internal structure, which lacked crucial positions such as a CFO and was understaffed in key areas. The GP also wanted a new CEO capable of carrying out its plans. It turned to Bryn Harrison, a former executive with Australian construction materials manufacturer Fletcher Building.

"They have a clear vision about what they want the business to be, and where they see opportunities to address some of the operating inefficiencies that the business has labored under," says Harrison. "And they were looking for someone with my background of distribution, building materials and operations and management to try and deliver those gains."

Customer care

The top priority for Harrison and his management team has been delivering a consistent customer experience across Carpet Court's 60 stores. Cosmetic revamps are part of this, but more important are behind-the-scenes improvements.

For instance, before the takeover Carpet Court had largely allowed its stores to keep their original financial and inventory systems and report to the central office on a monthly basis. This not only led to needless duplication of effort, but also meant that management couldn't assess market pressures or opportunities and respond quickly enough.

To address this issue Carpet Court has designed new computer systems to automatically collect the necessary information and report it to management on a real-time basis. Harrison and his team expect these systems, which are scheduled to go online by the middle of 2018, to expand their options considerably.

"It provides us a platform to do some much more powerful things around customer experience mapping, ensuring that customers are being contacted right through the purchase process and installation process rather than relying as we currently do on a lot of manual intervention," says Harrison. "A consistent information platform gives us the ability to drive business in lots of different directions that really have been limiting us until now."

Another of the company's goals is to clarify the relationship between head office and individual stores. Until now the chain has followed a mix of ownership models, including franchises, joint ventures and company-owned stores, set up on an opportunistic basis – another legacy of the previous owner's ill-thought-out acquisition strategy.

Harrison and his team are following up on this unfinished integration work by buying out franchisees and JV partners in some geographies and divesting to partners in others. The goal is to create a system wherein stores in metropolitan areas are directly managed by the company, while more remote locations are run on a franchise model.

In addition to enabling management to implement these reforms, Allegro has also put in place key performance indicators (KPIs) to replace the entrepreneurial decision-making process of the previous management with a more scientific, data-oriented approach.

One of the scores emphasized by Allegro is the "delivery in full, on time," or DIFOT metric, which measures the ability of a retail company's supply chain to fulfill its commitments. At the time of the acquisition Carpet Court's DIFOT stood at 60%, considered extremely unsatisfactory; as of the most recent assessment, it had improved to 99%, putting the business on a much better footing.

"It ensures that we've got the right stock for our 60 stores to sell; that when they want to order it we've got the key lines available; and that we can get it to them in time so they can service their customers," says Bou. "It's pretty basic stuff, but in a large business with a lot of operational complexity, it's not easy to achieve."

The other key metric introduced by Allegro is net promoter score (NPS), a measure of customer satisfaction based on surveys that ask clients whether they would recommend a product or service to friends and relatives. Scores range from minus 100, indicating uniformly negative views, to 100, indicating uniformly positive.

Allegro had experience with NPS from its ownership of Australian train operator Great Southern Rail and felt it would help with assessing performance in the heavily customer-centric world of home improvement. By this metric too, Carpet Court appears to be on track, having improved from a moderately positive score of around 20 to a result in the 50s, indicating highly favorable views.

Growth initiatives

With these building blocks in place, Carpet Court plans to leverage its unique strengths to achieve further growth. Its most notable advantage is its scale – despite the integration issues, its 60 locations make it by far the most widespread brand in New Zealand's flooring industry. This gives it a market presence unmatched by any other provider and should also drive business with larger corporate clients that prefer dealing with a single supplier rather than contracting with a different service provider in each location.

Carpet Court's scale also helps it with its stock. While most of New Zealand's flooring companies source their material from one of two domestic suppliers, Carpet Court has a partnership with US-based Mohawk Industries, one of the world's largest manufacturers of soft and hard flooring products. This means the company can offer customers a much wider range of options.

The final new initiative is to add other home improvement business lines. Customers are likely to need multiple products and services along with flooring, and the company believes it can sell these as a natural extension to its traditional offerings. Carpet Court has already introduced window finishing to its business and expects to add more options in the future.

"That industry shares a lot of similar characteristics to floor coverings – a lot of independent small operators, an inconsistent customer experience, big-box players that are involved but probably not delivering a high-quality experience," says Harrison. "You can go even further into places like other interior decorating and finishing trades, such as paint, plaster, and those sorts of things."

Allegro is pleased with Carpet Court's performance so far, but still sees considerable room for improvement before the company is ready for exit. The firm has already received inquiries from strategic players, and it expects other financial sponsors to be attracted as well. The key is to build a robust organization that can handle itself well under any owner.

"At Allegro we believe in better, and that means looking at best practices in whatever businesses we're involved with to ensure that our portfolio companies are sustainable," Bou says. "If we do that, we believe value will solve itself."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.