Long-term capital: The patient play

Permanent and long-term capital structures are an attractive proposition for a wide range of players in Asia’s PE market, but bringing them from theory into practice presents numerous challenges

For Eric Solberg, founder and CEO of EXS Capital, the elephant in the room for Asian private equity is expressed in a single chart comparing the last 30 years of the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the Hang Seng Index. "I basically can cover the long-term line representing the Dow with my pencil and it tracks almost perfectly. It's a very smooth curve, with a bit of a bump in 2008," he says. "But when you look at the Hang Seng, or any market in Asia, they are like a roller coaster in comparison."

Public market volatility in Asia is no secret, but Solberg sees this feature as more than a challenge for individual investors. To him, Asia's constant boom and bust cycle is a systemic issue that cripples the viability of the PE model itself, which locks GPs to strict time frames for investment and fundraising. While this is not an issue in markets where growth is historically steady – if slow – in regions with high volatility even the best managers can fall victim to market downturns that are beyond their control.

"On the Dow Jones line it doesn't really matter when you raise your fund, when you make your investments, and when you get out, because it's a relatively stable curve. What matters is if you're making good investments and managing them well," says Solberg. "But in Asia you might look great for one three to five-year period and bad in the next."

His is not an isolated opinion. In recent years, various market participants have expressed increased dissatisfaction with the traditional 10-year private equity fund structure, stimulating interest in vehicles that go beyond its perceived limitations. Longer-term and permanent capital structures are recognized by a growing cohort of GPs and LPs as having the potential to address some of their most persistent concerns about investment performance.

But reports of mounting enthusiasm for longer-term capital pools must be balanced against the reality that so far, few such vehicles have emerged in the region. This is due to a number of factors, particularly the relative youth of the industry in Asia, which exacerbates LPs' uncertainties about whether managers can handle a vehicle outside their comfort zone. In the end, while many believe there is a place for permanent or long-term capital structures in Asia, actually filling that niche may require a leap of faith on the part of GPs and their investors.

The global dynamic

The slow adoption of longer-term funds can be puzzling given these structures seem to enjoy wide support. In a global private equity market survey by Intertrust last year, more than 50% of LPs said they expected permanent capital structures and funds with a duration of 15-20 years to grow in popularity over the coming five years. This appeal is driven by the flexibility of being able to hold portfolio companies over longer periods of time and continue to add value, the ability to invest in sectors promising longer-term investment horizons was also highlighted, and better liability matching.

Several global GPs have responded by introducing funding structures that allow them to deploy capital over a longer period. KKR, The Blackstone Group, Apollo Global Management and The Carlyle Group all have such pools: KKR said that its permanent capital vehicles accounted for more than $5 billion of the $39 billion it raised in 2017, while Apollo raised $16 billion for its permanent capital funds last year out of $60 billion of net asset growth.

Some of these vehicles target specific asset classes that are seen to benefit from longer hold periods: Blackstone and Apollo both manage real estate vehicles with a permanent fund life. Others are intended to complement existing PE strategies. Carlyle Global Partners (CGP), established by Carlyle in 2014 with $3.6 billion in investment capital, is focused on control and non-control investments in attractive companies that can benefit from a holding period of at least seven years. It targets sectors where the GP already has considerable experience, with a geographic focus on North America and Europe.

"Our goal was to set up a fund that actually is intended to access longer duration (i.e. different) deals, not to try and make those deals fit into a traditional mold," says Eliot Merrill, a managing director and co-head of CGP. "We think traditional buyout funds are fit for a huge number of companies, but we also think there are companies where duration can make a difference. If we have a vehicle with a longer duration, we can then access those deals for our LPs."

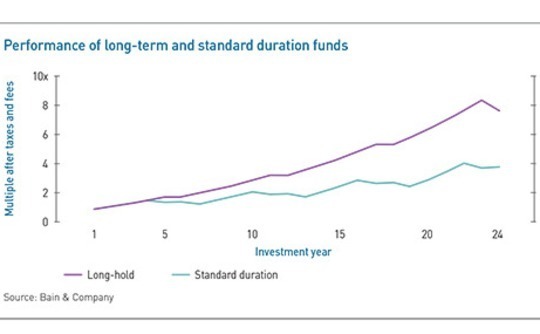

A recent study by Bain & Company would seem to justify investors' enthusiasm. In its most recent global private equity report, the firm modeled the performance of a long-term PE fund exiting a company after 24 years, versus a typical PE investor purchasing and exiting four companies through multiple funds over the same period. It found that the long-hold fund reached almost twice the total returns of the short-duration vehicles over the same period.

What LPs want

This does not mean that longer-term structures are inherently better managed than traditional funds. Bain's analysis assumed that the portfolio companies performed in an equivalent manner during the period of review, with the improved returns coming from eliminating transaction fees, deferring capital gains taxation and keeping capital fully invested. But for LPs, particularly larger investors, these findings are significant.

"What you find is that these substantial pools of long-term capital would prefer a consistent return, a regular deployment and working of their money, and protection of their principal," says Mounir Guen, CEO of placement agent MVision. "They don't want you coming back to market every two years, and to have to reassess whether they're going to support you or not. They'd really like their money to be tied up and put to work."

Another motivator for LPs can sometimes be simple convenience. In particular, certain sovereign wealth funds and pension plans – which are short-staffed based on the amount of capital they have to deploy – can easily feel that their time is taken up with decisions that are largely made on autopilot.

Lorna Chen, a partner at law firm Shearman & Sterling, recalls working with an Asian GP on designing a long-term capital structure five years ago. That fund never got beyond the planning stages due to lack of LP demand, but from 2016, the firm started to receive inbound interest from LPs looking for investments that could streamline some of the more time-consuming aspects of the business.

"In recent years their capital has kept increasing, but their teams either remained the same size or at least did not increase as quickly as their capital grew," says Chen. "The burden to deploy capital is so big, and they usually decide to top up after a quick discussion anyway. So why not just give the money and not worry about topping up?"

Along with convenience for LPs, adding longer-term structures to Asia's investment mix could help build strength among the region's fund managers. Asian GPs are still largely perceived as inexperienced on an institutional level compared to their Western counterparts, and some market participants suspect that the explanation lies with their marriage to a business model that is poorly suited to the characteristics of their market.

"The success rate of GPs in Asia, on both a relative and absolute basis, has been surprisingly low," says Solberg of EXS. "And it's not because there aren't talented people out there. It's got to be because of some kinds of structural reasons in terms of the market working differently. In our view, the simplest explanation is how different this market is in terms of volatility."

Solberg claims to have seen Asian GPs fall victim to public market volatility in several ways. First, if a manager finds it easiest to raise capital when the markets are performing well, this will influence his pace of investment. He may find himself under pressure to deploy capital soon after closing – to alleviate the j-curve effect – which means investments are made when the market is peaking. The danger is a downturn comes towards the end of the holding period, assets are exited at the bottom of the market, and returns suffer. Fundraising becomes that much harder the next time around.

"You want a vehicle that can almost trade around the closed-end funds," says Solberg. "You can exit to the closed-end funds, because in the market today they have more capital to put to work, and their argument internally is we're not being paid to sit around – we're being paid to allocate capital. But with a permanent pool you could sell into that, and then when markets go into crisis you can buy."

A longer holding period by itself would not completely counter the issue of volatility, as money still needs to be deployed and assets need to be exited to generate returns, and market downturns are a regular issue. But a GP that is not facing pressure to exit immediately could wait for a more opportune moment and divest its assets when the market is on the way up again.

"Having a three or four-year fundraising cycle doesn't necessarily match their capital requirements. It's just a consequence of the traditional PE fund model," says Justin Dolling, a partner at Kirkland & Ellis. "Certain investors have also expressed frustration with investments being flipped multiple times between different PE sponsors, and there's a clipping of the ticket each time investments are flipped."

Going public

So, if there really is an appetite for longer-duration private equity structures among Asian GPs and their investors, why have these models have so far failed to gain traction in the region? Industry participants see the primary problem as a lack of precedent.

While established GPs have set an example of a permanent capital approach, it is not feasible for smaller investors, since these larger firms also have several other vehicles through which assets can be acquired. For a GP that is currently on its second or third fund, selling LPs on a new vehicle just to hold companies over a longer period, locking up their capital for longer, can seem daunting, even if the proposition seems reasonable.

Private equity firms may instead create listed vehicles that can raise money on the public markets, as KKR and Singapore's Symphony International have done. This type of structure can offer more freedom for both the GP and its investors, who can trade in or out of the fund at any time.

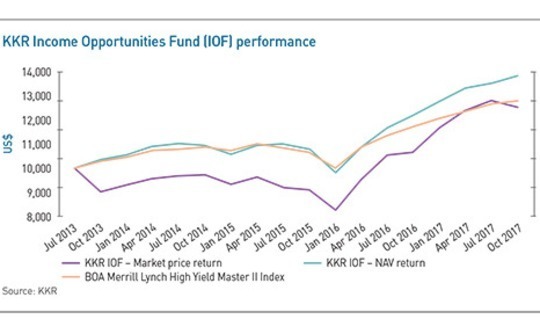

But the structure poses its own challenges, chiefly that investors seem to consistently undervalue them. For example, KKR's Income Opportunities Fund, a listed vehicle that invests in credit instruments, has traded at a significant discount to net asset value (NAV) since its launch in 2013, as has Symphony. Observers attribute this to a fundamental lack of transparency inherent to the private equity model.

"In a typical hedge fund, it is easier to mark to market the portfolio as the underlying investments are usually more liquid than a typical PE fund, giving LPs a relatively high degree of confidence in the NAV marks," says Dolling. "In contrast, where a fund has a relatively small number of illiquid investments whose value can vary significantly on exit, it becomes much more difficult to determine a reliable NAV at any point during the term of the fund. This is challenging in the context of an open-ended fund where the sponsors economics and entry/exit of LPs is usually based on NAV throughout the life of the fund."

The very fact that KKR, Apollo, and other global GPs have these vehicles can also discourage adoption by the wider private equity industry. These vehicles, with a built-in pedigree, have the potential to monopolize investors' attention, particularly from the largest LPs who are most interested in the long-term investment opportunity but are unlikely to risk their investment on a relatively new manager trying an unproven strategy.

This reflects on the primary barrier to the adoption of long-term funds in Asia: despite the possible advantages to LPs, managers in the region are for the most part perceived as being simply too inexperienced and risky to let them venture far from the typical PE approach.

"A lot of the pros can be flipped around into cons. If everything's going well, that's great, it saves hassle – but if things aren't going so well, suddenly you're locked in for a very long time," says Gavin Anderson, a partner at Debevoise & Plimpton. "Also, even at the most stable and well-run shops, you get personnel changes, and issues can arise. If you've got a fund that's running for 20 or more years, the likelihood of things happening during that period can be a bit higher."

Liquidity matters

Structuring can be a challenge for permanent vehicles too, particularly around the issue of liquidity. In a traditional PE fund, investors gain liquidity at the end of the fund life, but this is not possible with permanent vehicles for obvious reasons. One solution is to allow LPs to choose to exit the fund at certain points – for example, every five years – and if they choose not to exit they must stay in until the next liquidity period.

This approach works in most cases, but it has its own complications. For example, LPs will likely expect a clawback provision to ensure that the GP has not taken too much of the profit pool. In a traditional structure this is simple, because all LPs receive their clawbacks at the same time. But when some LPs joined at different times than others, calculating who is due what becomes harder.

"On the one hand, the LPs will still be looking for a clawback, but knowing that this is a relatively permanent type of product, they cannot expect to claw back forever," says Shearman's Chen. "Deciding how far back you go when you negotiate the clawback period is very challenging, and it varies from product to product."

Long-term structures are immune to some of these problems, since they can be based on traditional fund models with a longer holding period. But negotiation will be required here as well, since LPs may justifiably expect some flexibility on fees given that the attraction of the structure is based on a perception of lower risk.

The issues around structuring largely come down to the fact that permanent and longer-term models are still in the conceptual phase in Asian private equity – they may be cleared up when managers begin to introduce these funds in earnest. But many market participants remain skeptical that this will come to pass, due to the hesitance among GPs to take the first step. Most believe the waiting will continue for the foreseeable future.

"There's a lot of interest in the concept, and certain sponsors/investors can definitely see the attraction of such funds. The issue is that when people drill down into the detail and try to get their head around some of the practical issues it becomes difficult. It really requires a sponsor and group of likeminded LPs to make the commitment to work through these issues to get it done," says Dolling.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.