New Zealand PE: Hidden gem

Private equity is taking a bigger piece of New Zealand’s small economic pie. Investors must act opportunistically to exploit substantial potential in an inconspicuous but engaging middle market

Investment professionals in New Zealand sometimes characterize the country as on track to be the Sweden of Asia Pacific – a traditionally parochial and agricultural economy that now resonates with sophisticated global consumers through high-value brands. For local private equity players, this is a promising setup.

Wellington-based Pencarrow Private Equity offers a recent example of how this scenario is playing out with the sale of outdoor winter apparel company Icebreaker to VF Corporation, a US-based competitor that markets under household names such as The North Face and Timberland. Transaction details have not been disclosed, but the big picture says much about how private equity can help New Zealand‘s understated growth stories attract international attention.

Icebreaker was already active outside of New Zealand when Pencarrow and government-controlled investor Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) bought a 38% stake in 2015 for NZ$124 million ($90 million). However, the company needed help improving margins and resolving supply chain inefficiencies. Pencarrow saw what is considered a quintessentially New Zealand value-add opportunity.

"We invest in companies that are under the radar of offshore private equity investors but can be built up through a combination of organic growth and bolt-ons until they are attractive to overseas PEs and strategics," says Nigel Bingham, a managing partner at Pencarrow Private Equity. "We not only grow EBITDA and revenue – we're actually very likely to get a significant multiple increase as well. That's why funds targeting businesses under NZ$100 million in enterprise value tend to do particularly well in this market."

Far-flung

New Zealand's low global profile contributes to its appeal as a private equity hunting ground in a number of ways. Perhaps most noticeably, the country's geographic isolation tends to prohibit international players from swooping on businesses as they graduate to the growth-stage sweet spot that local GPs are targeting. From an economic view, more nuanced cultural factors appear.

The market capitalization of all companies on the New Zealand Stock Exchange typically represents less than half of the national GDP. US and Australian stocks, by comparison, fluctuate above the 100% mark, sometimes eclipsing 140%. In New Zealand, this ratio is often evoked to imply that local businesses are undervalued, but more incisively, it flags a prevailing preference for private economic activity.

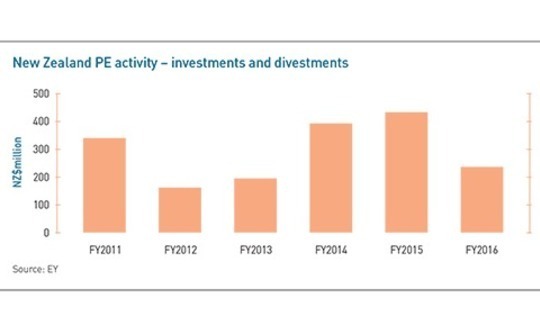

The opportunity set for private equity in this context is further supported by a relative lack of professional capital supply. According to EY, total mid-market PE activity, including investments and divestments, has fluctuated in a modest range of NZ$160-430 million during the five years through 2016. Fundraising across all private equity and venture capital topped the NZ$1 billion mark for the first time in 2016.

Pencarrow and Auckland-based Direct Capital jumpstarted this evolution around 1993-1994 in a financial environment now seen as anachronistic. Early funds were required to be listed so institutional investors could track then on a daily basis. Buyouts were regularly transacted with no professional sell-side advisory whatsoever.

"I recall the first investment I ever worked on, the discussion with one of the few banks we could interest in partnering with us focused acquisition debt on asset backing alone. There was no concept of cash flow lending," says Gavin Lonergan, a director at Direct Capital. "It's quite humorous looking back. Today all of the banks have teams that are set up to work with private equity sponsors – likewise with the professional services firms, each of whom has well-established corporate finance teams."

As banking and professional service firms responded to the emergence of private equity, the maturation process accelerated. The prevailing theme of the past 10-15 years has been substantial increases in the number of managers and in the diversification of their LP bases. Middle market deal flow during this period has been underpinned by overseas expansion ambitions and demographics-driven succession issues.

Sizing the opportunity is a firm-by-firm process. Direct Capital has identified around 950 potentially investable companies. Its most recent fund closed at NZ$375 million and is claimed to be large enough to address the upper half of the domestic middle market. In a given 12-month period, Pencarrow monitors about 100 midcap companies out of a field of 5,000.

Younger firms targeting this space include Maui Capital, Waterman Capital, and Pioneer Capital, with the latter looking at about 150 small to medium-sized enterprises (SME) a year with a strong focus on export-oriented businesses. Among the most recent generation of entrants is Milford Asset Management, which launched a NZ$150 million PE fund in 2016 and scopes a target market of 2,500 businesses with annual revenue of NZ$20-200 million.

Differentiating factors

Despite this proliferation, industry professionals insist that head-to-head competition remains relatively rare. This also reflects the intimate nature of the M&A market. Deal activity is personal and the use of financial engineering is less aggressive. Although a handful of larger Australian firms – such as Pacific Equity Partners (PEP) and Archer Capital – play at the top end of the market, the bulk of the opportunity set is being carved up discretely by local investors with minimal outside participation.

"The number and size of the funds out there is small relative to the overall stock of investable capital," says Joshua Pringle, a partner at Chapman Tripp, who has worked with a number of local GPs. "It doesn't feel like there are too many PE players chasing the same opportunities, particularly given the often proprietary nature of deals in the New Zealand mid-market and the differences in philosophy between the funds."

These differences in philosophy are also critical to the latest generation of GPs on the LP side of the equation. Since the bulk of PE fundraising has traditionally appealed to only two firms, ACC and New Zealand Superannuation Fund (NZ Super), managers have been under significant pressure to present a unique story.

For Pencarrow and Direct Capital, the differentiation factor is size and reputation. Other players are obliged to be more creative. Pioneer's export focus, for example, has leveraged advantages in overseas businesses experience to curate a portfolio that generates 95% of its aggregate revenue offshore. One of the country's newest GPs, Oriens Capital, positions itself as a specialist in regional companies and partnered with Pioneer on its first investment.

"The larger private equity firms have been really welcoming to us because they know that we are filling a niche in the market that's not really a competitive threat to them," says James Beale, CEO at Oriens. "We've had partnership discussions with quite a number of the larger New Zealand private equity firms around transactions that perhaps we had better insight into because they were regional businesses, but we may not have had the capability to fulfill the transaction."

Oriens has secured about NZ$50 million for its debut fund with a view to making minority and buyout transactions in companies operating outside major urban centers with enterprise valuations of NZ$10-50 million. Last year, it joined Pioneer to take a combined 55% stake in Rockit, a company that sells tubes of specially bred miniature snack apples across a number of international markets.

The basic arbitrage with regional SMEs is analogous to the New Zealand strategy globally – acquire positions in assets invisible to the larger players and scale them for an exit to strategic investors and later-stage GPs. Nevertheless, local investors report that PE penetration at this level of granulation remains challenging due to the defensive posture of small companies unaccustomed to welcoming new shareholders. The effect is doubled in New Zealand's rural South Island, where Christchurch-based Genesis Private Equity claims a hyper-niche advantage.

"Being based down here, we've got proprietary contacts that a lot of the bigger firms in the North Island don't have and don't really bother with because they're interested in bigger businesses," says Nathan Mills, an executive director at Genesis. "Right throughout the country, that's one of the reasons none of the investments we've made so far have been contested. We're operating in a different sort of geographical area with stronger networks and targeting a different range of opportunities."

Genesis closed its debut fund in 2016 at NZ$11.9 million and has made three investments to date, including two technology companies and a holiday homes operator. Fundraising was initially hampered by a downturn in the dairy industry that spooked rural LPs, but ultimately, the untapped nature of the jurisdiction's scattered investor base has proven an overriding factor.

Local money

PE firms have reported a dramatic expansion in the overall LP base in recent years from a narrow dependence on NZ Super and ACC to a range of small charitable trusts, religious endowments, family offices, high net worth individuals, and international groups. Pencarrow, for example, closed a bridge fund in 2016 at NZ$80 million with two Australian LPs and has received interest for its next vehicle from US investors.

Due to their small size, however, New Zealand funds invariably lean on domestic players by scraping together large numbers of small checks. It has become common for local managers to tally up to 150 LPs, mostly micro investors, in a single fund. This is not just a theme for the unproven first-timers – Waterman closed its third fund in 2016 at NZ$200 million with more than 100 LPs and no participation from its previous anchor NZ Super.

The unique aspect of this trend is the emergence of a wealth base among the indigenous Maori people, which represent some 15% of the total population and have secured substantial government settlements in the past 20 years. These investors, known as iwi groups, are increasingly recognized as sophisticated, patient and attuned to regionally-based growth opportunities. Pioneer closed its third fund last year at NZ$210 million, achieving almost one-fifth of the corpus by tapping this resource.

"New Zealand Maori groups like private equity because they like real assets and the resources and specialist skills that a GP brings," says Randal Barrett, a managing director at Pioneer. "It suits them as an asset class because they're very long-term investors as well, so they can handle illiquidity. I would anticipate that all New Zealand private equity funds will wind up with iwi investment in them, and that the 17% we secured in Fund III will soon become the normal level."

Diversification has also been an important indicator of maturity in the exit market. Trade sales, while still the preferred path, are now far from the sole realistic option for many of the branded, value-added technology and export-ready consumer sectors coloring the modern PE landscape. New momentum in secondary sales to international GPs offers a case in point, with PEP acquiring a number of businesses from local GPs in recent years, including Manuka Honey, a health food company considered well below the Australian investor's usual targeted range.

IPOs have also evolved to encompass a wider range of company sizes, with enterprise values of NZ$50 million now seen as having the potential to go public. Direct Capital offers a standout track record in this space, with robust floats in recent years for food companies King Salmon and Scales and a runaway success with Ryman Healthcare. The firm invested Ryman at an equity value of NZ$23 million in 1996 and listed it in 1999. It is now worth about NZ$5.3 billion.

The traditional sector preferences of these IPOs, however, betray a persistent provincialism that even the largest players must negotiate with care. This in turn reflects the intimate nature of the overall business environment as well as the need for patience and a personal touch in the processes around building trust.

"New Zealand s a smaller market and the six degrees of separation common in other markets is more like two degrees of separation here," explains Direct Capital's Lonergan. "Reputation counts for everything and we have worked hard throughout our 24 years to ensure that the partnership DNA we have continues. It is a core part of how we judge ourselves."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.