VC holding periods: Delayed gratification

The traditional IPO exit timeline for early-stage investors is being pushed out as technology companies raise additional private funding rounds. A more thoughtful approach to securing liquidity is often required

Nexus Venture Partners will host LPs at its annual general meeting later this month and outline plans for its next fundraise. Wooing investors historically hasn't been a problem for the Indian venture capital firm. Its fourth fund closed at $450 million in 2015, with most of the capital coming from existing LPs. Nexus is one of India's best-known local GPs and early guidance given to investors suggests it expects a similarly smooth fundraising process. However, Snapdeal remains a problem.

Nexus first backed the e-commerce company in 2010 and ended up supporting it across several funding rounds. The VC firm had opportunities to make partial exits as Snapdeal soared to a valuation of $6.5 billion in early 2016, but it resisted calls from several LPs to generate liquidity, according to sources familiar with the situation. Twelve months later, the Snapdeal story had turned on its head. SoftBank, another investor, agitated for a trade sale to direct rival Flipkart at a valuation of $1 billion.

The deal never went through and Snapdeal remains a fraction of its former self. Nexus had marked the position as high as 13.9x based on $39 million of invested cost and $548 million in unrealized value. The most recent valuation suggests the VC firm will get its principal back plus a little extra. The fund that accounted for the bulk of the investment was on course for a 5x return. Now it stands at 2.7x.

Nexus is not the only early-stage investor to take a hit on Snapdeal, but two of the others, Kalaari Capital and Saama Capital, at least made partial realizations. The situation is seen by many as a lesson in how a longer holding period can come back to haunt a VC firm. With IPOs being pushed back in favor of additional private funding rounds, it has resulted in closer scrutiny of a GP's ability to manage an exit well: securing liquidity to cover the downside while retaining enough equity to enjoy future upside.

Questions such as "How long is too long?" and "What price justifies an exit?" reverberate around the industry. There are no right answers. However, VC investors must still try and strike a careful balance between meeting the sometimes conflicting needs of their investors and maintaining relations with founders who wield considerable influence over the timing of exits.

"It further amplifies what the issues about VC have always been – potentially high TVPI [total value to paid in] if you pick the right funds but delayed DPI [distributions to paid in]. The current trend we are seeing in terms of delayed IPOs and further private funding rounds is uplifting the potential TVPI and also pushing back exits," says Wen Tan, co-head of Asia Pacific private equity at Aberdeen Standard Investments."

Indian angst

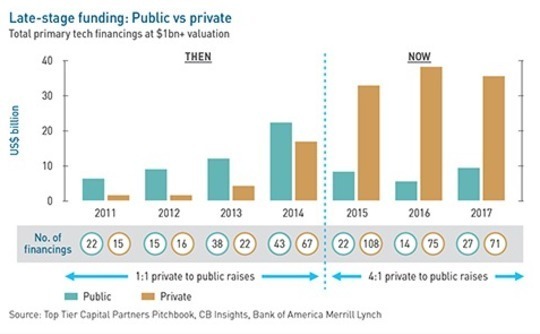

The challenges presented by delayed distributions involving companies that have achieved unicorn status through progressively larger rounds featuring hedge funds and private equity are not restricted to India. The holding period for many early-stage investments globally has extended from 5-7 years to 9-13 years, leaving plenty of unrealized assets from 2005-2007 vintage China funds, for example.

Snapdeal stumbled because, like several of its local consumer internet peers, it reached scale but didn't have a market-leading position. The company needed more capital and no one was comfortable enough to participate at the requested valuation, effectively trapping the early-stage investors. Situations like these are exacerbated by the lack of a robust domestic M&A environment and public markets that are not yet attuned to technology plays.

"While we have seen the beginnings of some M&A from the bigger unicorns, it's predominantly in stock. Only two acquisitions of $100-500 million in the consumer space in the last five years have been for cash. And we don't have the metrics to back up large public exits, even on NASDAQ," says Karthik Reddy, co-founder and managing partner at Blume Ventures. "We have struggled to show those massive exits."

Blume was an investor in TaxiForSure, which previously occupied second place in India's ride-hailing market, behind Ola and ahead of Uber. Ola purchased the business in 2015 for $200 million, one quarter in cash and three quarters in stock. Blume took out some money at the time of acquisition, but there has been no liquidity since then. While Ola returned to the market last year and raised $1.1 billion, the valuation was lower than in previous rounds. Reddy explains that the company was unwilling to consider allowing secondary sales "until it had settled the issues around primary money."

"We have seen several situations where the GP is willing to sell because their mark-to-market is pretty healthy and can take a substantial discount to the previous round. But the company itself needs to raise primary capital, which means the founder is not aligned with the GP because they are fighting for the same pool of funding," adds Praneet Garg, a managing director at Asia Alternatives.

Limited rights

This highlights the difficulties early-stage players can encounter even when they want to exit and a replacement backer is standing by to enter – through a new round of funding that includes some primary capital or the direct sale of shares to a secondary investor. While most investment agreements come with a redemption mechanism, these are seldom activated: if a right is triggered on one round then all other investors can redeem as well, creating a domino effect that neither founders nor VC backers really want to see. The preferred option is to secure the founder's blessing.

"It's all down to communication and explaining what you are trying to do. Founders don't want too many VC guys trying to exit because it creates negative sentiment, so you have to work with them. They understand that we are in the business of generating returns, so you have to make sure these points are discussed in a thoughtful and open manner," says Vertex Ventures CEO Kee Lock Chua.

Situations in which founder and investor are unaligned can create reputational damage as well. Venture capital firms don't want to be seen as belligerent partners because it could ruin their relationships with founders – who might be serial entrepreneurs with plans to spawn dozens of other companies – and dissuade other start-ups from working with them.

These considerations must be weighed against the need to return capital to LPs, but there are all manner of other factors. Jireh Li, chief representative in Commonfund's Asia office, recalls asking a VC firm if it had considered selling just 1% of its 15% stake in a start-up. The principals said they had but were reluctant to pursue the matter for fear of upsetting the founder. At the same time, they thought there was much more upside to the company and did not want to forgo potential higher returns to LPs or upside in carried interest.

Furthermore, it may be impracticable to complete a secondary transaction without the cooperation of a company's board, its management, or existing preferred investors. Some investment agreements include lock-ups on share transfers, restrictions on transfers to a company's competitors, right of first refusal and tag-along rights for the benefit of the company or other shareholders. While in the US, VC investors will strenuously object to contractual restrictions on transfer, Thomas Chou, a partner and co-head of Morrison & Foerster's Asia PE practice, notes that the practice is more varied in China.

"With the top-tier companies raising capital in China, management is often successful in imposing some restrictions on an investor's ability to transfer," he explains. "The most common would be a restriction transferring such shares to a competitor of the company. In a minority of deals where the company enjoys very strong demand, investor transfers may be subject to a right of first refusal or a tag-along right. In extreme cases, the investors may be forced to (reluctantly) agree to a straight lock-up for a fixed period of time."

It helps to time partial exits so they coincide with the entry of strategic players: this might be seen as counterbalancing the departure of early-stage backers with the arrival of supporters equipped to take companies through the next stages of their growth. In the absence of new capital – where existing shares are sold to a secondary investor – transactions can be a tougher sell.

"If you do a secondary direct into a company they may not entertain you performing financial due diligence because you are not injecting new money. You are a substitute for another investor and a founder might see that as a less appealing proposal," says Paul Robine, CEO of secondary investment firm TR Capital. "You need to convince them that you bring them something different. The future winners in the secondaries space will be those who not only buy at attractive prices but also show they can add value."

The Xiaomi story

Early-stage investors are increasingly turning to the secondary market as a source of liquidity, resulting in all kinds of portfolios of unicorns or single positions being shopped around. The former tend not to require founder approval, while the latter do. "They are starting to realize they have to take money off the table. They can't sit and wait for the final outcome because it's distorting IRRs and investors can't tolerate waiting 15 years," says David York, CEO and managing director at Top Tier Capital Partners.

However, the exit timing game works both ways. Chinese mobile phone manufacturer Xiaomi raised equity funding in late 2014 at a valuation of $45 billion, but two years later the company's rapid growth had caught up with it: handset sales were down, supply chains were challenged, and ambitious plans for international expansion weren't delivering. Industry sources said early last year that stakes in Xiaomi were available at valuations of $20 billion or below, but some insisted they wouldn't buy at any price because it was impossible to properly assess what the company is worth.

Xiaomi is now being touted for an IPO at a valuation of $100 billion. This turnaround is based on an offline retail strategy and an investment portfolio constructed with a view to creating a technology ecosystem. Several hundred stores have been rolled out offering Xiaomi's core consumer electronics as well as products manufactured by at least 20 hardware start-ups in which the company has invested.

"E-commerce is 15% of retail and penetration is increasing by one percentage point a year. You can wait for the online market to grow or you can try offline retail. Having so many products from the Xiaomi mall, it has been positive from the get-go," says Hans Tung, a managing partner at GGV Capital. "The company is now a combination of Apple, Amazon and Cosco. It's like when Amazon first started it was selling books; no one knew it would become a Hollywood studio too."

Tung invested in Xiaomi in 2009 while working for Qiming Venture Partners. The VC firm provided seed funding and subsequently re-upped, but then made a partial exit from the company during the round prior to the one at a $45 billion valuation. LPs are complimentary rather than critical about Qiming missing out on what seems likely to be additional upside.

They note that Qiming was also the only investor to make money on Vancl, an online clothing retailer that was poised for a US listing in 2011 before an expansion strategy intended to build up market share went painfully wrong. The venture capital firm generated a 2x return on its investment by taking some money off the table when the opportunity arose. Vancl is still operational but it has been written down to close to zero in most funds that have exposure to it, according to sources familiar with the company.

"Things can change very quickly. Some folks were pointing fingers and saying Xiaomi was going through a rougher patch two years ago, but now bankers are pitching themselves to be its IPO champion," says Commonfund's Li. "I never go back to a GP and ask, ‘Why did you sell?' We as LPs have to trust our GPs' judgment. If a GP is upset that it could have made another $100 million, that's when you remind them that situations like Vancl and Snapdeal do happen so you just have to make a decision based on existing knowledge and foresight. This industry is, after all, about disruption."

Using influence

Ultimately, it is not necessarily an LP's place to tell a venture capital firm when to sell a position: they have entrusted capital to the GP based on a belief that it knows how to manage a portfolio of companies better than they do. The onus is on suggestion rather than direction, but even though exchanges might be increasingly frequent as holding periods lengthen, feedback from investors is seldom uniform.

This is exacerbated by the contrasting natures of LPs often found in venture capital funds. The investors who were most vocal about Nexus' position in Snapdeal are said to have been fund-of-funds. These groups often have executives based in Asia – so they might have a clearer viewpoint than LPs who aren't as close to the ground – and they also want to show returns to their own investors. Endowments and foundations, which focus on long-term accretion, represent the other extreme.

Edward Grefenstette, CIO of The Dietrich Foundation, a US-based charitable foundation with strong exposure to Asia, admits that he advises GPs not to be unduly influenced by the DPI benefit. He tells them: "You work hard to invest in and develop an asset that is initially a ‘black box,' of sorts. After 3-4 years, you now presumably know that asset considerably better. Thus, trust your judgment if you have visibility on turning a 5x return into a 7x if you hold the asset a little longer, because the risk-return profile associated with that incremental 2x is likely much more attractive than a fresh investment."

The key skill required in this context is portfolio management, and Grefenstette argues that it is becoming easier to single out the more sophisticated operators as the Asia market matures. For him, the acid test is whether a GP has the conviction to explain to LPs that it is forgoing a 5x cash offer for a company because it expects the exit environment to be even better in two years' time, rather than sacrifice long-term returns to bolster DPI ahead of a fundraise.

It is an assessment tailored to the needs of a foundation and unlikely to be endorsed by all LPs – notably those that believe a fair number of Asian venture capital firms still lack portfolio management experience and find it hard to walk away from assets when they see significant upside. Nevertheless, a GP with conviction in itself, the makings of a track record, and the ability to rationalize decisions about longer holding periods, is more likely to be given the benefit of the doubt.

For example, it has been suggested that Paytm could cause a similar amount of economic and reputational damage to SAIF India as Snapdeal has inflicted on Nexus. Certainly, there is a lot of unrealized exposure – amounting to more than $1.3 billion across three funds – in a business that saw its valuation hit a reported valuation of $7 billion last year. But SAIF has also locked in realizations of $360 million, or 5x its invested cost. That is enough to assuage LPs' concerns, at least for the time being.

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.