India LPs: Patient capital

Despite favorable regulatory moves in recent years, Indian financial institutions remain reluctant to invest in private equity. Investors see room for optimism, but they know they are in for a long wait

Ascent Capital knew it faced a tough sell. Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC), the state-backed insurance fund, was one of the GP's most reliable backers, having supported its first three vehicles. But returning to market last year with Fund IV, Ascent recognized that the world of Indian private equity had changed. A re-up was by no means guaranteed.

"It took much more time across the command chain. We had to pursue the entire set of decision makers there," says Subhasis Mujumder, a director at Ascent. "But finally they decided to invest in our fund, albeit at a much smaller size than they had before. We consider that a positive sign, because at least they have not shied away from the asset class."

While Ascent's pitch was ultimately successful, the difficulty it faced securing LIC's commitment points to a broader challenge for the private equity industry: the continued reticence of domestic financial institutions to back Indian investors. Despite regulatory changes intended to encourage investment in the asset class, the fundraising scene is still dominated by high net worth individuals (HNWIs) and family offices.

Industry participants insist there is interest in private equity from the institutional investor community – and a certain degree of participation – but the overriding sense is one of wariness. This is rooted in the turbulent history of the asset class in India as well as a lack of familiarity with it. Change could come in venture capital, where smaller fund sizes may be more attractive to investors looking to get their feet wet. However, the consensus view is it will take several more years before domestic institutions consistently make up a sizeable portion of the country's fundraising scene.

Attempts to mobilize

This minimal representation is not for lack of trying. Several recent regulatory measures have aimed to loosen up India's alternative investment fund (AIF) regime, which was first set up in 2012 to make it easier for managers to domicile investment vehicles in India than the previous venture capital fund system. The AIF structure gives PE and VC funds tax pass-through status, meaning that income is taxed at the investor level rather than the fund level.

"Traditionally we didn't have a local pooling mechanism that was tax-efficient if you had foreign investors coming in from offshore jurisdictions to invest in a pool," says Pratibha Jain, a partner at Nishith Desai Associates. "When the AIF regime came in, the first effect was to promote the family offices and high net worth individuals to invest in these vehicles."

While family offices and HNWIs were the first to benefit from the new structure, it was never the government's intention to stop there. Subsequent changes to the AIF regime have encouraged institutional players to take part. Insurance firms were given permission to invest in the funds in 2013, and the National Pension System (NPS) followed in 2016. Banks, meanwhile, were temporarily barred from investing in Category II AIFs (which includes most private equity funds) by the State Bank of India in 2016, but this restriction was lifted last year.

These investments are not without limits. Pension fund managers under the NPS can only invest in funds with a corpus of at least INR1 billion ($15.7 million) and cannot account for more than 10% of the total fund size. In addition, AIFs can make up a maximum of 2% of the pension's total portfolio. Insurers face similar restrictions on commitments to individual funds; also, life insurers can only invest 3% of their portfolios in AIFs, while general insurers are limited to 5%.

But such restrictions are seen as a minor hurdle by an industry eager to gain access to this' capital. The year before the NPS gained permission to invest in AIFs it had more than INR1 trillion in assets under management, which if invested up to the limit would provide over INR20 billion for private equity industry. The question for many is why institutions have shown little interest in rising to the occasion, and even reduced participation from previous levels.

"Ten years ago the banks were more active in Indian private equity. Today they are not doing that much, though they might back a couple of GPs with whom they have good relationships, that they want to continue to support," says Sunil Mishra, a partner at Adams Street Partners. "Outside that type of relationship I would be hard pressed to believe that there is a lot of domestic institutional LP demand in India to support private equity fundraising. It's mostly high net worth individuals and family offices."

Mishra's observation is echoed by other industry participants, who say managers can still gain commitments from institutions with whom they have an established history – as with Ascent and LIC – but GPs looking for support from previously untapped investors find it nearly impossible to make their case. Managers looking for domestic capital largely rely on investments by individuals and family offices.

Unfortunate past

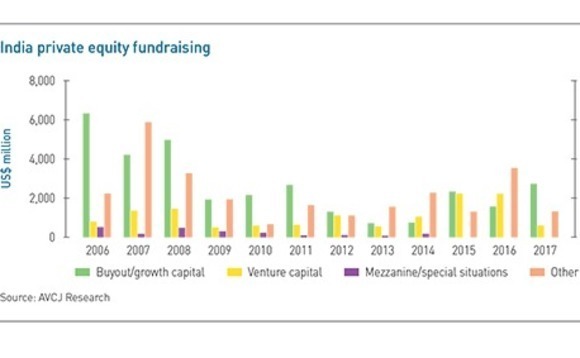

A good deal of blame for this institutional reticence is placed on the shadow cast by private equity's rocky history in India, particularly the funds that raised large amounts of capital in the 2007-2008 vintages but had significant difficulty delivering satisfactory returns. Investors who remember those challenging times say it might be for the best that India's institutions are taking their time with the asset class rather than jumping in with both feet before they are ready.

"While some very good fund managers came out of that experience, there were clearly some managers that shouldn't have been seeded in the first place," says Nupur Garg, head of South Asia private equity funds at the International Finance Corporation (IFC). "Periods of high euphoria can lead to an increased probability of mistakes and poor judgment calls."

Venture capital is the exception to the rule of institutional reluctance to commit to AIFs. Once again it is the government that is leading efforts to catalyze investment, though in this case it is acting more directly, supporting VC managers through the Startup India initiative and measures such as the India Aspiration Fund, a INR100 billion fund-of-funds announced in 2016 and run by the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) and its investment arm SIDBI Venture Capital.

The extent to which government participation is advisable over the long term is debatable. The segment has its own attractions compared to growth capital – "Venture investment does make for a more glamorous conversation at tea parties and cocktail parties," as one industry participant put it. Additionally, some express concern that participation by the government, whose priorities are more socially than fiscally oriented, could end up distorting the market.

However, observers acknowledge that SIDBI VC, which claimed to have disbursed over INR17 billion by the end of 2016, has become a powerful force in the industry. Moreover, the government believes that as an anchor investor in funds by VC investors such as Blume Ventures and Innospring Capital it can encourage reluctant institutional investors to take on the asset class.

"SIDBI has become a first port of call for most of the new funds being launched. After that it's insurance companies, and in some cases, banks have also started seeking exposure to such products," says Munish Randev, CIO of multi-family office Waterfield Advisors. "Insurance companies are targeted because their investment horizon matches the long-term horizons for these funds."

The government has also begun to support the growth equity market through the National Investment & Infrastructure Fund (NIIF), launched in 2015. Here too the goal is to pursue developmental goals through direct investment while mobilizing additional investors to contribute.

But the extent to which this strategy has paid dividends is debatable. Outside of growing interest by banks in venture debt vehicles, participation by the country's financial institutions in venture capital and private equity continues to be limited.

For GPs that do manage to secure backing from these groups, the reluctance can be a positive. Ascent's relationship with LIC has helped it gain access to other public insurers, which are reassured by the larger firm's vote of confidence. While access to sources of capital that are denied to other managers can be a huge advantage in fundraising, support from a traditionally wary constituency is not absolute. If one leading institution cuts back its commitments others might follow suit.

The long game

Most observers remain optimistic that India's financial institutions will find their way to the private equity market. GPs say that although commitments have been slow to materialize so far, their contacts with institutions such as banks and insurance firms claim to be making plans to get involved.

However, they still need time to create investment plans and build confidence in potential investees. In addition, the major institutions have enough investment opportunities at present that there is no pressing need for them to branch out into other asset classes.

"With demonetization a lot of money went into the banks and other financial channels, and they will be looking to invest that money. But I think their first goal will be to invest in listed equities," says Adams Street's Mishra. "Once they build their public exposure, the next step may be building private exposure. It is still early days, but I think as financial assets continue to accumulate that will lead to a higher level of demand for the domestic alternative investment industry."

Managers on the ground emphasize that they see institutional capital as a long-term development. In addition to the inherent hesitance, GPs must also keep in mind that when these investors do enter the market they will still be relatively inexperienced. Even if they come equipped with well-researched investment plans, they will be wary of committing large amounts of capital until they have gained more experience.

"At the end of the day, out of the money that gets invested here, a large part will still come from large global funds," says Vishal Tulsyan, managing director and CEO of Motilal Oswal Private Equity. "I expect at least five to 10 years will pass before we see a good amount of participation coming from the domestic institutional pool, though I do feel the domestic HNWI and family office pieces are really becoming large."

Despite the likely long wait, investors active in India remain eager for the arrival of institutional investors – and not only the GPs. Other LPs look forward to working alongside domestic institutions, both for the support they can bring to the private equity ecosystem and for the confidence they can mobilize for global investors who have their own reasons for holding back from India.

"For the longest time all of us in the emerging markets have been complaining about the global sentiment towards this country – there was a period when India was off many investors' charts," says IFC's Garg. "The availability of this domestic capital will help to reduce that fundraising risk, and when domestic institutions with a long-term view of the economy are willing to take a long-term illiquid position, it can create a very positive signal for the market."

SIDEBAR: HNWIs and VC – The personal touch

The LP universe in India is diversifying as high net worth individuals (HNWI) and family offices continue to institutionalize and executives at professional investment houses pursue fund commitments in their own capacity with increased frequency. Perhaps unsurprisingly, venture capital has represented the vanguard of this evolution.

The most fundamental explanations for the shift are a reduction of bureaucratic barriers to business-building and that fact that the fast growth of the technology space is becoming an increasingly powerful drawcard for investors across the board. However, LP diversification has less to do with macro transitions and more to do with nature of the investors themselves.

For example, while HNWIs are prone to back funds due to their lack of PE experience, they are also typically characterized as entrepreneurial types who are keen to take risks at the cutting edge of their respective domains of expertise. Angel group and family offices are also becoming increasingly professionalized, hiring dedicated staff and launching formal investment programs. More money is consequently entering the start-up ecosystem, pursuing direct deals and backing VC funds.

Bengaluru-based venture investor 3one4 Capital recently highlighted this effect with a INR2.5 billion ($39 million) final close on its second fund. The fundraise exceeded its target of INR1.5 billion thanks to a raft of domestic LPs including institutions, independently active fund managers, and family offices such as that of entrepreneur Mohandas Pai – whose sons Pranav and Siddarth Pai are 3one4's founders.

"This may be the only fund I've seen with such a large GP participation," says Pranav Pai. "Having shown LPs that we're putting our own money at risk the same way they are, and what the outcomes we're optimizing for look like – that's what convinces them. It's not just about ‘I know him' or ‘she knows him'. That has never worked actually."

Fund II raised INR1.5 billion within three months last year and exercised a greenshoe option to add another INR1 billion through hand-picked LPs with strategic capabilities and networking value in core investment areas. Notably, the vehicle was supported by four co-founders of IT consultancy Infosys, where the elder Pai worked as CFO, including Narayana Murthy, who participated via Catamaran Ventures.

Other investors included executives with Indian backgrounds at offshore firms such as Westpac International and Amansa Capital, as well as veteran domestic institution Reliance Ventures and Madhusudan Kela, who stepped down as chief investment strategist at Reliance Capital last year. The reveal: the new wave of local LPs driving Indian venture funds isn't necessarily as inexperienced as one might expect. They were simply waiting for the right moment to strike.

"What we've seen as LPs, and what LPs we've worked with have told us, is that the right set of circumstance has now converged," Pranav Pai explains. "The explosion in Indian participation in venture is not because LPs were unsophisticated – it's because they were sophisticated enough to know the timing wasn't right even two years back, but it is now."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.