Fund placement in Asia: Beyond beta

Not all PE firms in Asia are benefiting from the fundraising boom. Placement agents must sift through a bifurcated market and identify managers with potential and mandates that are economically viable

CDH Investments is every bit the blue chip Chinese private equity firm. It is a pioneer in the country's alternative assets space, having accumulated more than $17 billion across multiple strategies. Investors have generally been more than happy to add to the private equity capital pool. Funds III and IV, for example, were among the largest ever seen in China yet they closed in a matter of months.

By the time CDH launched its fifth US dollar-denominated fund in 2012, though, conditions had changed. The GP was seeking more capital than for the previous vintage and investor sentiment had weakened. Once fundraising gathered momentum it finished strongly – the hard cap of $2.55 billion was hit in early 2014 – but the entire process took nearly two years.

This time around CDH is leaving little to chance. It is targeting $2.5 billion for Fund VI and movement is expected in the LP base: the share of capital from fund-of-funds and endowments that were among the firm's early backers is likely to recede as contributions from pension plans and sovereign wealth funds increase. A placement agent has been hired to help manage this transition, and to make it happen fast.

For Park Hill Group, it is an intriguing mandate. CDH is a brand-name GP that has never previously sought third-party assistance in raising a flagship fund. But there is still an element of risk. Park Hill started working with CDH a year before the fund launched and could be engaged on the project for another 18 months. This removes it from contention for any mid to large China mandate for three years. Park Hill is just as keen as CDH for the final close to come quickly.

Debates over how best to deploy time and resources are routine for placement agents. However, those decisions have arguably never been more crucial. The fundraising environment is bifurcated: managers at the top end of the market are raising larger funds at short order, but for those in the middle market the outlook is less certain. No one wants to work on a mandate where the hours, or years, put in far exceed the economics taken out.

"It's a bit like the deal side. In the past people have taken a beta bet on the market and the rising tide means everything does well. But in the placement agent world you now have to be extremely careful in terms of which mandates you take on," says Niklas Amundsson, a managing director with Monument Group. "Even though it's a good fundraising environment overall, you have to maintain discipline and not get overexcited about opportunities because things can change very quickly."

Size matters

CDH, thanks to its scale and track record, remains a major player in a shallow China market. It can attract investors that write large checks – and size is a key factor in the current fundraising boom. The past four years have been Asia's most productive in terms of attracting capital, but a disproportionate amount of it has gravitated to two areas: renminbi-denominated funds and large-cap US dollar vehicles.

"Global fundraising has been incredible, almost pre-2008 levels. When you come to Asia, fundraising has been increasing overall, but when you look at it on a currency basis, the US dollar share has dropped in the last couple of years and the top 10 funds are an increasing percentage of the pie," says Chris Lerner, a partner at Eaton Partners. "When you combine those factors, it has created a very competitive and challenging market for mid-size funds."

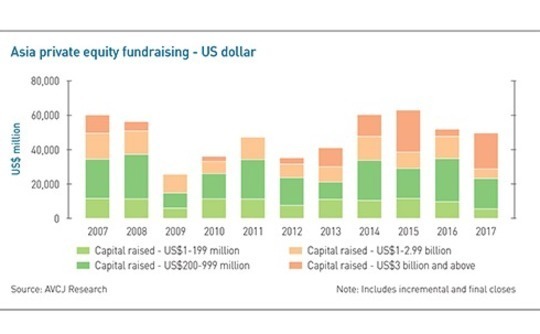

This prognosis is borne out by the numbers. Strip out the renminbi portion – it is beyond the reach of mainstream placement agents – and 2015 is the high point with $62.5 billion raised. Commitments have fallen off since then, reaching $49.4 billion last year, according to AVCJ Research. Since 2014, funds of at least $1 billion have accounted for 46% of all capital raised. In 2015 and 2017, the share going to vehicles of $3 billion or more alone topped 39%.

KKR and Affinity represent the two extremes at the top end of the market as far as placement agents are concerned. The former has a large investor relations team working on multiple strategies; it has no need to outsource. Affinity, which raises capital once every 3-4 years and therefore has little need for substantial in-house IR resources, does. Other large pan-Asian players that are indigenous to the region, like Baring Private Equity Asia, MBK Partners, and PAG Asia Capital, also tend to use agents.

The basic rationale behind the placement agent's role is unchanged. With a full-service offering, much of the work takes place ahead of the fund launch. Duties may include advising on the positioning of the fund, helping map out the existing LP base – establishing which groups are likely to re-up and which could be difficult – and figuring out how to fill strategic gaps in the LP base. This is followed by initial approaches to investors, gauging appetite for the product.

"If you are focused on fundraising every four years, it makes sense to deal with a specialist that is always in the market. Placement agents are much more up-to-the-minute on what LPs are looking for. They allow you to focus your time efficiently and productively," says Nick Bloy, managing partner at Navis Capital Partners. "We've never seriously considered bringing the function in-house."

Once the groundwork is completed and the fundraising process officially begins, the onus switches to project management: opening data rooms; issuing private placement memorandums; setting up meetings with LPs and making sure the relevant people arrive prepared and on time; addressing regulatory and compliance issues; and dealing with the flood of documentation and follow-up questions that arises during due diligence.

"Some of this isn't hard, but when you're getting 100-page due diligence questionnaires and requests to provide clarification, the IR person is swamped. This is particularly the case when dealing with pension funds that have fixed committee dates and templates," says one middle-market manager. "Also, sometimes you just want someone to say no – if you don't want to let an LP into your data room or you think they are asking inappropriate questions."

Varying needs

However, the prevailing market environment means that the needs of PE firms vary greatly. As one first-time GP explains, hiring an agent was a no-brainer; none of the principals had hands-on fundraising experience from their previous roles. Dealing with the uncertainty that surrounds a first-time fundraise was especially challenging. LPs professed interest but were hesitant about committing, simply asking to be kept informed of the progress. Even one month before the final close, it wasn't clear who was for real.

The likes of Affinity sit at the other end of the spectrum. The Fund V process was expected to move swiftly with a high proportion of re-ups. A number of other LP relationships were managed directly by the GP. According to a source familiar with the fundraising, Affinity's priority was finding an agent to help shoulder the back office burden. One prerequisite was that the group had a global network, so it could facilitate GP-LP relations efficiently in different markets.

As a result, mandates such as these are not necessarily the most lucrative. Agents usually only receive a performance fee for new money brought into a fund, and if re-ups and carve-outs are numerous, there is little scope for additional participants. In some instances, a private equity firm might abandon the tradition of paying a percentage fee based on capital raised and opt for a flat fee instead.

While there is a tradition in Asia of certain managers using the same agent for consecutive fundraises, these relationships evolve over time as the GP becomes more institutionalized. "In the beginning, we were building the brand and developing a core LP base," says an agent who has worked with an Asia-based manager across multiple vintages, stretching from multi-million-dollar to multi-billion-dollar vehicles. "For the last two funds our role was limited. We were there for diversification and speed."

The economics tend to reflect this changing dynamic, yet many agents see value in retaining the business: the two parties are familiar with one another; fundraising is swift, so despite the reduced fee, it represents a reliable source of income; and being associated with a successful PE firm is good for their brand. The latter two reasons might also prompt a rival agent to try and steal the mandate by submitting a very low bid.

Competition for mandates and compensation that is geared toward accelerated project management have squeezed margins in this segment of the market. A partnership committee might recoil at the prospect of earning as little as $1 million on a $3 billion fundraise, but it is a function of resources and opportunity. Is that mandate more desirable than working on a full-service offering with a riskier mid-market player, such as a first-time GP or a manager that needs to rebuild its LP base?

Even among managers in the latter group, the traditional model of a meaningful retainer plus a 2% commission on all new capital raised is seen as past. However, variations on the structure still exist. Several agents say they receive around 1.75% across all funds with all manner of clauses baked into an agreement. These are intended to reflect both the challenges and priorities of the fundraising in order to preserve an alignment of interest between agent and manager.

For some mandates, compensation is no longer linked to reaching a certain amount of capital or number of LPs in such a binary way. An agent might receive a flat fee for processing a pre-agreed volume of commitments, based on the GP's expectations in terms of re-ups by existing investors, and then larger bonuses if the fund hits its target and then its hard cap. Adjustments can be made upwards or downwards in response to the re-up rate.

"We want to be in a situation where, irrespective of how a fundraising has gone, both parties walk away thinking it was a good outcome," explains one placement agent. "We want to avoid situations where an agent has ended up raising nothing but the fee was based on the fund size so they get $10 million and the GP hates them and rubbishes them to the market."

Changes in fee structures are the consequence of a more sophisticated market. The perception that fund placement is a rolodex business – a private equity firm raises what it can from its own network, achieves a first close, and then pays an agent 2% for whatever they bring in on top of that – persists in some parts of Asia, but attitudes in general have evolved. Greater emphasis is placed on strategic advice provided ahead of the fund launch and its impact on the overall outcome.

Selection issues

Nevertheless, raising capital for these funds is harder than before. "You need a blended and diversified portfolio of funds and that blend is constantly changing in response to evolving market conditions. Assume a quarter of funds are easy to sell, a quarter of them are hard to sell, and the other two quarters in between these two extremes are of varying degrees of difficulty. The issue in this current cycle is that the upper two quarters are generally shrinking and the bottom two quarters are expanding," says Vincent Ng, a partner at Atlantic Pacific Capital.

As a result, every agent is spending longer on manager due diligence, prioritizing bottom-up research over macro plays. Beyond that, there are three general strategic initiatives: go zero-risk, go niche, or go direct. An agent's response is largely dictated by the number of mandates it can take on globally at any one time and the number of strategies it is permitted to cover.

Eaton Partners, for example, opted for the niche approach in China, abandoning generic growth capital managers in favor of groups that are more specialist in nature. The five final closes it had in the region last year included Hosen Capital, C-Bridge Capital, and GenBridge Capital – three China GPs that focus on food and agriculture, healthcare, and consumer, respectively. Other agents seek to capture different market cycles and dynamics by increasing their exposure to real estate, real assets, and credit.

Among most industry participants, there is a wariness of taking on placement mandates for direct investments, although this is tempered by a recognition that there is both supply and demand for such products in Asia. Some agents, usually those affiliated to larger financial institutions that have an investment banking arm, can't do them. Others restrict their involvement to servicing GPs with which they have a pre-existing relationship.

MVision is the exception. Direct investment mandates, typically in the form of separate accounts backed by one or two LPs, account for about 30% of its pipeline business and CEO Mounir Guen expects that share to grow. He gives two reasons for this. First, there are not enough talented managers in Asia to absorb the quantum of capital that large international investors want to deploy in the region. Second, he is not convinced the traditional 10-year fund structure is best suited to the needs of these investors.

"I really expected a higher rate of new entrants. It isn't happening because there isn't enough capital to make it work," Guen says. "Big chunks of capital are available from large investors, but you need products. I would like nothing more than to create new GPs. We are no longer mapping the market in terms of what GPs are coming to market, but in terms of individuals who we can raise around."

This approach can, in theory, create a longstanding client base; a new GP might prove itself on a deal-by-deal basis and graduate to larger separate accounts or traditional comingled funds. However, these projects are time-consuming – taking perhaps twice as long as the 9-12 months allocated for a mandate with an established manager – and there is uncertainty as to the market response. A strong conviction on the part of the advisor, underpinned by careful due diligence, is paramount.

A tough sell?

Launching an unproven product can be especially challenging in an Asian context given the placement agent responsible is simultaneously marketing other funds on a global basis. A distribution executive in New York tasked with covering the North American LPs is far more comfortable pitching a US-based manager that he and his clients know well than an unorthodox opportunity out of Asia. The performance of private equity in the region as a whole compared to the US is also an issue.

A number of Asian GPs have experienced being turned down by agents as an unattractive prospect or being accepted but relegated to the back of the bottom of the pile below funds that are seen as more appealing to LPs. The harsh reality is that relatively few private equity firms in the region have international brand-name recognition and this makes them a harder sell. And while validation by the Asian LP community can be important, it lacks the depth and ability to mobilize capital of other markets.

Coupled with the bifurcation between haves and have nots, these factors have made the process of matching capital with managers more complex. But for placement agents that are careful in the selection and positioning of GPs and in the timing of a fundraising, these obstacles are not insurmountable.

"Sometimes you just need to be patient," says Michael Henningsen, a managing director with First Avenue. "With quite a few fundraises, you see there has been a struggle in the early part and then the market they are in becomes more attractive, some exits come together, or a first close gets done, and this injects momentum. Helping GPs understand that those issues can play a significant role in how a fundraising may play out is very important."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.