India energy: Power trip

A sudden shake-up in the economics of India’s energy sector has piqued investor appetite to the point of indigestion. As the market settles, a long-term growth story appears set to support a range of industries

India, perhaps more than any other nation, services as a concise microcosm for the choppy economic rise of Asia as a whole. A chaotic mix of variously developed states, it is complex and unevenly growing, but likely to be a world leader within five years.

Nowhere is this difficult but indisputably promising profile more prominent than in the country's energy sector, where progress has been colored in equal parts by sluggish bureaucracy and dramatic quantum leaps. From an investor's perspective, the core theme has been a government agenda to enable economic modernization through rural electrification and increased general power supply.

Both skepticism and confidence are high since most of the investment action of late has been in the unproven but unstoppable renewables space. Private equity features in some of the best examples of this momentum, including Tata Cleantech Capital (TCCL), a joint venture between Tata Capital and the International Finance Corporation that has invested about $400 million in India and has an aggregate power capacity of about 4 gigawatts.

"There are states where enforceability of contract needs improvement, but what gives us comfort is that while we've seen delays in payment, we have not seen any defaults," says Manish Chourasia, a managing director at TCCL. "We have financed more than 100 projects in the past five years and we don't have any non-performing assets in our books. As long as we are dealing with a decent developer with good financial flexibility, the chances of something going wrong are low."

The most prominent driver of recent investor interest in Indian energy has been a sudden collapse in the cost of renewable energy, particularly solar and wind, which have both coincidentally been priced as low as INR2.4 ($0.04) per kilowatt hour this year. This represents about a 50% drop in the cost of clean energy in the past 18 months, putting renewables on grid parity alongside conventional sources of power.

Policy support

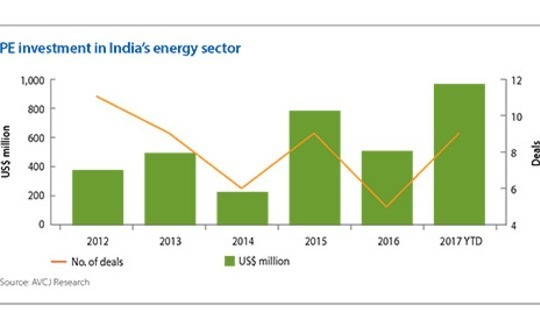

Investment in renewables has consequently accelerated – and stirred concern about the sector overheating. According to the International Energy Agency, energy investment in India jumped 7% during 2016, ranking the country third behind China and the US. Globally, it was the first year investment in the electricity industry surpassed investment in fossil fuel supply.

In India, this new environment is largely underpinned by government initiatives, including the commonplace provision of 25-year offtake agreements and the implementation of a reverse auction mechanism for energy pricing in place of feed-in tariffs. The resulting competition among energy companies to lower costs has put pressure on margins and raised doubts about projects' long-term viability in the event of unexpected operational disruptions.

However, the overall supply-demand scenario and the notion that a policy framework is gradually solidifying have been almost universally encouraging. Tim Buckley, a director at the Institute for Energy Economics & Financial Analysis (IEEFA), sees the slide in renewable costs as a "transformational" event, especially given that it was achieved without providing material subsidies that are not also available to thermal power companies. He notes nevertheless that solar and wind prices are now 50% below new import thermal power generation tariff requirements.

"To me, that's effectively game over," says Buckley. "It's now just a matter of time for that to be built into the system and for the Indian energy minister's own plan to be put in place in a very cost effective manner because it's deflationary to consumers, and that's a story that no market in the world has seen until this year."

Enthusiasm for the renewables bump has been tempered at the deal level by nerves about frothy valuations and a renewed sense of realism about counterparty risk in a transitioning energy market. In the longer term, things can get even more opaque.

Industry feedback confirms that state-owned power distribution companies that had previously agreed offtake deals at higher prices are now looking to renege. Although the impact of these legal retreats may be minimal in dollar terms, they have raised questions about sovereign risk at a time when renewables are precariously dependent on government underwriting.

Furthermore, it may be too early in the evolution of the market to put too much stock in the latest technologies. India is still the second-largest producer, consumer and importer of thermal coal globally. About 80% of electricity is generated by fossil fuels, the use of which is expected to double within 15 years on the back of rabid domestic power demand.

Counterpoints to the renewables story also explore the notion that India's clean energy targets may be overly ambitious given the severity of the national supply-demand gap. This is especially concerning considering a relative lack of enforceability and political reliability. China is seen as India's guiding example for energy sector self-reinvention, but it benefits from a more authoritative government regime.

India is now aiming for about 40% of its power capacity to be from renewable sources by 2030. Electric vehicle targets, meanwhile, are even more aggressive. The government said earlier this year that it expected every car sold in the country to be electric by the end of the next decade.

"There is a lot of excitement around renewables, and of course it will work over the long term, but in the meantime, India still needs to reduce its reliance on the import of oil and gas," says Sid Shamnath, founder and managing director at Tridevi Capital. "The government has set a much more realistic target in this area, which is to reduce oil and gas imports by 10% in the next 3-4 years. That's more doable because all that is needed is to have the policy in place."

Conventional question

Tridevi, a UK-based private equity investment advisory firm that is currently raising its first fund under the name Tridevi Advantage, maintains a strong focus on Indian oil and gas. Recent activity includes a $20 million investment in coal bed methane (CBM) operator Deep Industries. CBM is a relatively cheap and compact gas extraction technique used on un-minable coal deposits that is enjoying regulatory favoritism in India because it can quickly offset the pollution effects of coal burning at the village level.

The investment recalls that even as renewables continue their inevitable takeover of global energy markets, fossil fuels will not be phased out evenly across the board. While organizations such as IEEFA predict India will hit peak coal use within a decade, the country is expected to drive a 6% surge in global CBM use within two years while becoming the world's fastest growing oil consumer by 2035.

Energy security is also an issue. India is seen as compromisingly dependent on hydrocarbon imports from Russia and Qatar – a scenario that has fostered a number of policy moves to encourage international investment in domestic oil and gas.

Private equity has struggled in this space, however. Most notably, The Carlyle Group launched a $500 million equity line targeting upstream South Asian oil and gas properties under the name Magna Energy in 2015, but the program appears to have failed to make a single investment. Tridevi therefore advises working in a smaller ticket size range of $20-40 million or less, with a vigilant eye on difficult local factors around land access and exiting restrictions.

"Something that's quite important here is that, even during preliminary assessment of a specific deal, we always look at the exit routes available to us," says Alex Dimitriou, a senior associate at Tridevi. "If we perceive a bit of a squeeze, we might not proceed with it."

The idea that there is room for private equity at both ends of the energy spectrum has been directly embraced by Actis Capital, which is bullish on gas as well as renewables. In India, the firm has made a $77 million investment in 2010 in GVK Energy, one of the country's first independent power developer with capacity across gas, coal and hydro.

Activity in the meantime, however, has been decidedly renewables-focused. Although Actis bills itself as technology agnostic, its energy funds have primarily invested in renewables. The firm maintains five investment platforms, of which one is gas and the rest are cleantech. Earlier this year, it raised $2.75 billion for an emerging markets energy fund that is expected in part to follow up progress charted by its existing Indian platform Ostro Energy.

"We've ended up playing in both thermal and renewables in India not so much because we made a decision about diversification but more because it was a function of where we were in the industry's evolutions," says Neil Brown, a partner at Actis. "The big change between our second and third vintages was the cost position for wind and solar. When we were investing in GVK, renewables were a lot further behind than they are now."

Actis approaches energy in the country with caution, noting opportunity in the size and trajectory of the market, but warry of recent episodes of overbidding for projects with tight economics. It sees the demographic and policy particulars as better suited to operational scaling than many other Asian jurisdictions.

Technology tests

A school of thought persists, however, that while political initiatives have helped jumpstart the renewables scene, their long-term impact on the competitiveness of solar and wind will be limited. Future progress in reshaping the country's energy space will have to be driven by technological advances, especially in energy storage, a critical hurdle in smoothing out the peaks and troughs of renewables' production patterns.

"Battery costs are coming down by about 15% per annum, so in the next 2-3 years, we're going to have a situation where storage of renewable power plus production will be cheaper than power production from base load fossil fuels and as reliable," says TCCL's Chourasia. "When that happens, it will lead to a bigger disruption than we're seeing now."

Petroleum investors are no less cognizant of the technology factor. Last year, government entity Oil & Natural Gas Corporation launched a INR1 billion venture fund to support start-ups capable of injecting innovation into a stagnant domestic production space. Likewise, Tridevi's CBM play, which is the first PE investment of its kind in India, represents a technological solution to immediate bottlenecks in the fossil fuel market.

Technology-driven segments like CBM will also be necessary to stem the environmental impact of India's increased fossil fuel use across the next 15 years, which could in turn jeopardize the current policy environment. With a particularly thick haze descending on Delhi this month, pollution is starting to make headlines and seriously influencing political discourse for the first time. Prime Minister Narendra Modi is up for re-election in 2019 and could face charges that the government is tackling the worst particulate levels in the world with a plan that would make them worse – despite investor fervor for renewables.

"This is a country where people don't even have enough electricity to power their homes seven days a week, and now they're expecting to have all electric cars in 12 years," says one industry professional active in the country. "If you're an investor in renewables infrastructure, you'll be very excited today, but the renewables targets will not be met, and the policy will change in a few years when the new government comes in."

Energy, however, is a long-term game that plays across political cycles, and there is evidence that India will continue to be an attractive jurisdiction for disciplined investors. The country's economic overhauls in the past year, including demonetization and a new tax regime, have had minimal impact on energy companies. But they signal that the government is committed to economic modernization and could be a more bankable underwriter of electricity offtake contracts.

"It's absolutely globally significant what's happening in India because they're looking to ride on China's coattails but with 5-10 years of technological advances baked in before they make any changes," says IEEFA's Buckley. "India is in a situation where they have to work out how they're going to spend probably $500 billion on their electricity sector over the next decade, and they're looking at a relatively clean spreadsheet."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.