India value-add: The professionals

Growing interest in control deals among Indian GPs means increased pressure to demonstrate value-add capabilities. Improving portfolio companies requires attention to the country’s unique corporate landscape

"When we initially started investing, promoters were reluctant to allow the GPs to have much input into their businesses," says Alagappan Murugappan. "So apart from providing some small value-add in terms of introductions, doing the company's research, helping them with board selection and things like that, it was mainly based on stock-picking."

Murugappan, a managing director for Asia funds at CDC Group, has seen India's private equity industry blossom from its initial reliance on minority growth deals over the last two decades. Investors now are increasingly confident taking a hand in the development of their portfolio companies, which are in turn more willing to listen to their PE backers' advice.

One likely beneficiary of this boost in value-add confidence is the growing number of local GPs focusing at least partially on buyouts. Various seasoned investors are professing eagerness to play a proactive role in taking businesses to new heights rather than waiting in the wings as founders or promoters take the lead.

Though this increasing appetite for control is likely to continue to spur developments in operational capabilities, even minority investors are now expected to take on an active role in positioning their investees for future growth. Value-add strategies differ among both groups, but they do share some aspects that GPs describe as vital to investing in India, such as an emphasis on relationships and personal connections.

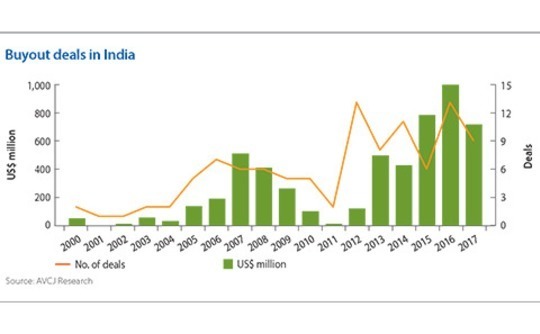

Data suggest that hopes for more buyout activity are being realized. According to AVCJ Research, Indian GPs completed 44 control transactions involving domestic companies between 2000 and 2011, an average of 3.7 deals per year (these data exclude deals by GPs based outside of India). But from 2012 to 2017 the total number of buyouts rose to 60, an average of 10 per year. Moreover, five of the most active years for buyouts over the past 17 years have occurred since 2011, with 13 transactions last year alone.

The amount of capital invested in control deals has also grown, with both 2015 and 2016 showing record levels of investment at $777 million and $989 million, respectively. Activity has also been strong so far this year, with $710 million committed across nine transactions.

Hearts and minds

For PE professionals that have been part of this history, the emergence of control is best understood in parallel with the willingness of company owners to accept the guidance of outside investors. Private equity's early stages in India are largely the story of a market more than happy to accept investors' money but far less welcoming to their advice.

From an investee's perspective, this arms-length relationship was understandable. Not only was private equity itself relatively unheard of at the time, many of the early investors had backgrounds in finance. The perception was that they might be very good at managing money and potentially a valuable source of industry contacts, but they were unlikely to offer much useful insight into long-term strategy.

"Twenty years ago, all that was needed to invest in India was a checkbook. That was a capital-scarce environment, and in a capital-scarce environment financial capital suffices," says Gopal Jain, co-founder and managing partner at Gaja Capital. "But today capital, timing and choices are not sufficient – you need another lever to create returns. That lever is value-add."

Over the past 20 years Indian GPs have labored to prove that they can be valuable contributors to a portfolio company's development beyond just providing capital. India's increasingly competitive commercial environment has presented them with an opportunity to do this, as management teams look for additional measures they can take to maintain growth.

"In an environment where corporate earnings have slowed down, you can't just assume that you'll be on autopilot and grow at 20% a year. You need to find ways to seek disruptive growth to gain market share," says Paddy Sinha, managing partner at Tata Opportunities Fund. "I think all our promoters and CEOs are quite conscious of that, quite aspirational, and want to deliver."

As GPs have gained experience, each has developed its value-add strategy in its own way. But while the specifics of each investor's approach varies, industry participants generally agree that there are three main ways to bring about improvement in a portfolio company. The first and most basic is corporate governance. For most GPs, this manifests as the right to appoint board members, although it is described as an often-overlooked tool.

"There are very few well-trained board members in India, and very few well-trained boards," says Gaja's Jain. "And I think one of the things that private equity can deliver to a company is a governance framework under which the board runs effectively, because the centerpiece of a corporation is a well-functioning board that empowers management to achieve goals that deliver value to shareholders."

Private equity firms have made considerable strides in this regard – strategic buyers seeking acquisitions in India often express a preference for PE-backed companies, which are generally seen to represent a level of professionalism and corporate governance superior to their peers

The second level of value-add strategy, follows from the first, since even the best-run company must have a plan to execute in order to grow. Sector specialization is the key to being able to contribute in this regard.

This does not mean focusing the entire fund on a single sector: a GP can identify multiple sectors for coverage. True North – one of India's earliest buyout funds, formerly known as India Value Fund Advisors – has assigned silos for its investment team in healthcare, financial services, consumer, and IT products and services. Other firms have established similar divisions, with varying degrees of formality.

"We identified business services, financial services, pharmaceuticals and healthcare and consumer services as effective sectors, meaning companies that did not urgently need money, but where we wanted to deploy money," says Sanjiv Kaul, a partner at ChrysCapital. "One of the characteristics of our outreach program is this proactive sector coverage – even when there is no transaction, our people go out and meet the promoters, and enter into a healthy discussion."

Adding strategic capabilities can be a bit more difficult for GPs, which may feel pressure to stay generalist in order not to limit themselves – True North remained officially sector-agnostic until earlier this year. But industry professionals say GPs have by and large accepted the need to focus on particular sectors, especially since India's economy is perceived to have reached sufficient depth that this strategy can generate enough deals to satisfy a firm.

The third level, operations, is the most significant contribution that a GP can make to a portfolio company but also the most challenging to achieve. This is because developing operational value-add capabilities requires considerable internal investment that often doesn't deliver a direct benefit in terms of deal flow. As a result, many managers have been reluctant to focus on this area, even though it is considered the only way to pursue an effective buyout strategy.

"Unless and until you have operating capabilities, you cannot really do control investing. But that requires a significant staffing response, which is why it's very difficult," says Gaja's Jain. "If you look at private equity firms in India, you realize the reluctance, because in order to build teams of a certain size you need AUM [assets under management] and you need a certain fee, but more importantly you need the willingness to spend that fee on people who are not doing deals."

This level of value-add is where GPs tend to differentiate themselves the most, with operational teams of varying size and sector competence. Dhanpal Jhaveri, managing partner for private equity at The Everstone Group, estimates that around half of the firm's team comes from a consulting, operating or sector-specific background and can be deployed to manage a portfolio company. In the case of ChrysCapital, Kaul heads an internal team dubbed Enhancin that focuses on value-add capabilities, a formalized version of the approach he developed for ChrysCapital at the firm's launch.

Despite the difficulty, industry participants say private equity firms aiming to establish a unique identity may have no choice but to put in the time and money to build their value-add capabilities at all three levels. Teams that fail to show they are taking the issue seriously run the risk of being left behind both in sourcing deals and in the ability to attract capital.

"While initially we were looking at stock-pickers, now I think we are much more interested in people who can assist with the transformation of businesses and with the growth and institutionalization of those businesses, and thereby make them more relevant for exits," says CDC's Murugappan.

Man at the top

One unique factor in Indian value-add strategies is the outsize level of importance of individual managers or groups of promoters compared to other markets. Companies in this market tend to be identified with their promoters to a large degree not only by customers, but also by corporate peers and regulators as well.

"The entity itself was less important than the people behind the entity who were doing business," says Everstone's Jhaveri. "Even when it is a very organized, formally structured business, the individuals or groups associated with it can provide a lot of comfort and credibility as a counterparty to various stakeholders."

This tendency to personalize companies with their leaders creates a challenge for private equity investors, particularly in control situations. If the promoter remains an active participant following the transaction, the GP must maintain a positive relationship with him or her, since even if it has a majority stake an unhappy promoter has the potential to create problems from a public relations standpoint or among suppliers and customers.

It may also be advantageous for a GP to keep a promoter with the company due to the more informal nature of the Indian market, though industry participants say this element is largely disappearing thanks to improvements in the country's corporate regulatory structure.

"There was a time when you needed an entrepreneur because even if you weren't corrupt, even if you weren't exploiting corruption, you needed someone to handle the system," says Gaja's Jain. "We have a long way to go, but there has been a discernible change in the level of probity, the general standards with which the system is conducting itself, and the need to compromise just to exist."

Even if the promoter leaves the company, the new owner can find the absence of a charismatic personality leaves a vacuum in the minds of other stakeholders that it is difficult to fill. A GP must be able to demonstrate the level of trustworthiness that stakeholders associated with the departed promoters.

Another challenge associated with promoter-led companies is they are often operated close to the margin of profitability, so it can be difficult for a GP to introduce growth-oriented initiatives that add to costs. "When it's a sponsor-run business the level of costs is usually already at a minimum," says CDC's Murugappan. "When a GP comes in and introduces more costs, unless there's a scale-up in business the margins suffer. And therefore it's much more difficult to make them succeed."

For private equity firms reluctant or unwilling to deal with promoters, there is another emerging buyout option: corporate carve-outs. These deals often provide much greater opportunity for improvements, since the division being sold off has usually suffered from a disconnect with its owner but is fundamentally sound. GPs in these situations can usually find more inefficiencies to correct.

Carve-outs are becoming a larger part of Everstone's strategy: the firm bought the bakery division of Hindustan Unilever last year and earlier this month purchased home appliance maker Kenstar from the Videocon Group. Jhaveri says a private equity buyer can provide additional levels of assurance to the corporate sellers due to the perception of greater professionalization on the part of PE-managed companies.

"A conglomerate may be looking to release cash to the group balance sheet, like Kenstar, or to divest non-core businesses as in the case of Unilever," says Jhaveri. "But in both situations there's a broader group that will continue to be active in the market, and it wants to make sure the successor will follow strong governance principles and make sure there's opportunity for customers, vendors, and other stakeholders."

Minority report

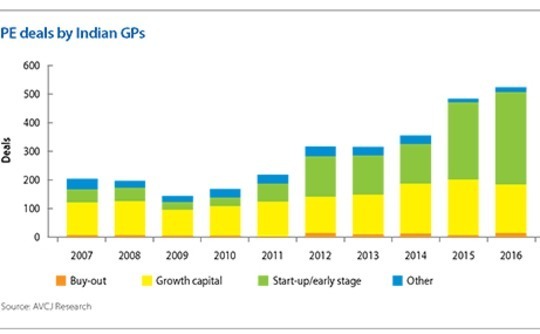

It is important to note that though the level of control deals is rising in India, the market still remains dominated by minority transactions – AVCJ Research has records of 166 growth investments last year compared to just 13 buyouts. However, while most transactions in India do not result in a majority stake, investors are finding that the same value-add skills apply.

"I think you can do all three levels of value-add even in a minority situation, but it depends far more on the relationship aspect than in a control deal," says Gaja's Jain. He and other investors say the personalized nature of investing in India means GPs that have established a good relationship with a promoter can often exercise enough influence to have their suggestions implemented even without the rights of a majority owner.

Minority investors are also likely to face increasing pressure on value-add from their LPs: as the performance of India's private equity market improves, institutional investors seeking to justify their commitments to a particular firm will call on it to demonstrate the ability to actively deliver returns.

"Where GPs have exited businesses, we look to see what role the GP played," says CDC's Murugappan. "We interview the promoters without the presence of the GP, just to get feedback as to whether they were conducive to the growth of the business and development or whether they were obstructive."

In the long run, however, investors agree that value-add capabilities are not something that can be taught. GPs with strong teams must build them through patient experience, and those that neglect the task do so at their own peril.

"We have to be sure that if we are buying a business we can actually do what we think we can with it, and that requires experience," says Everstone's Jhaveri. "In our case, the experience was initially doing smaller transactions that helped us build our capabilities and understand what works and what doesn't work. Today we are a lot more comfortable doing larger transactions."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.