Asia buyouts: The big get bigger

Asia’s pan-regional buyout players are raising ever larger funds and pursuing ever larger deals. Is there now more capital in this segment of the market than places to – sensibly – put it?

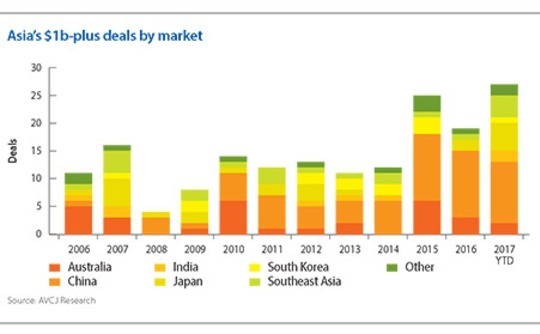

At first glance, PAG Asia Capital's acquisition of Yingde Gases appears to be a sign of the times. It is one of eight take-privates among 27 PE transactions of $1 billion or more announced – not all have closed – in the first 10 months of 2017. Investors have already deployed a record $176 billion this year, and those 27 mega deals account for 60% of the total. The region's top-tier investors are being bolder, and going bigger, than ever before.

But there is more to the Yingde deal than its $1.5 billion price tag. Over the course of four months from November 2016, the Hong Kong-listed industrial gas supplier's travails were broadcast blow by blow and disclosure by disclosure: its founders were involved in a public dispute; a share placement was announced then cancelled; there were repeated board reshuffles and management purges; and two rating agencies downgraded its debt to junk status.

With a strategic acquirer circling, Yingde launched a sale process. By then, though, PAG had completed two months of due diligence and negotiated separately with the major shareholders to win irrevocable undertakings over 42% of the shares. Supported by $1.5 billion in bridge financing, it submitted a general offer in early March and completed the deal within two months. The $2.7 billion enterprise valuation equated to 5.4x forward EBITDA, about half the level of Yingde's global peers.

"I tell the team to this day that we wasted two weeks for Chinese New Year, otherwise we would have done it even sooner and at an even lower valuation," says Weijian Shan, chairman and CEO of PAG. "The company was doing a share placement, so we were able to conduct due diligence. We got into the situation much sooner than everyone else, but we if we hadn't known the industrial gases industry so well we wouldn't have jumped up so quickly."

Yingde is an example of how a private equity firm acting with conviction can preempt a competitive process and secure an asset at an attractive valuation. However, it could be seen as the exception to the rule in a segment of the market characterized by larger funds, larger check sizes and greater competition for a relatively small number of assets, most of which are sold via auction.

"There are a greater number of opportunities as the Asian corporate and private equity landscapes grow in size, but at the same time, a lot of capital has come into the large end of the market," says Wen Tan, co-head of Asia Pacific private equity at Aberdeen Standard Investments. "Even though the opportunity set is growing, is there enough capacity to absorb everything that is being raised in this cycle? It's a debatable point."

Fundraising frenzy

Since the start of 2015, six pan-Asian funds have achieved final closes, raised by Baring Private Equity Asia, RRJ Capital, Bain Capital Private Equity, PAG, MBK Partners and KKR. The largest is KKR Asian Fund III, which closed in May at $9.3 billion, the most ever raised for a pan-regional PE vehicle. The average increase in size on the previous vintage for this group is 45%, and Affinity Equity Partners and The Carlyle Group – which are in the process of raising new funds – could increase it.

This is in part a global phenomenon. More capital is entering the asset class, but many LPs are looking to consolidate their GP relationships, committing more capital to a smaller collection of managers. The consequent increase in minimum check size means smaller funds cannot be considered. In addition, while many LPs believe they are underweight on Asia and want to increase allocations, a relative lack of familiarity with the region means they stick with familiar names.

"LPs are playing it safe – they don't want to take on too much risk, so they go after brand names," says Lorna Chen, a partner at Shearman & Sterling. "That is one of the main reasons why you see some of the larger funds get larger while first-timers are having even more difficulty finding investors and getting their size up."

A recent global study by TorreyCove Capital covering the 2000-2013 vintages found that funds below $500 million outperformed the rest, but by a small margin: the average net IRR was 14.7%, compared to 13.4% for $5-7 billion funds and 11.6% for funds of $7 billion and above. However, the standard deviation between top and bottom quartile narrows with size: 17.1% for the sub-$500 million players compared to 9.2% and 7.2%, for the upper two size bands.

"We are seeing allocators globally taking that trade-off," one Asia-based placement agent observes. "They are giving money to firms they think are highly institutional and have stability because they are willing to accept returns that clear their global hurdle for investing in alternatives for what they might hope is slightly less dispersion than if you do everything with small-cap players."

No similar studies have been published for Asia specifically, but it is generally acknowledged that the gap between top quartile and bottom quartile across all fund sizes is larger than in the US or Europe. Some investors also carry scar tissue from an earlier focus on growth capital plays in China and India. It proved harder for companies to achieve IPO exits than in the previous generation, and some LPs have responded with a renewed appetite for larger funds pursuing control transactions.

"We've limited our deployment in ‘traditional' growth capital versus more control-minded proposals – we want to avoid seeing our managers buying small stakes in companies with an IPO as sole exit plan, which could potentially leave them stuck for a number years," says Eric Marchand, an investment director at Unigestion. "We still see a number of traditional growth capital funds doing well, hence we may be missing some interesting opportunities. But we believe our focus is on the market segment which is developing, and the opportunity is going to be huge for years to come."

There is also the possibility of taking on transactions that previously would have been beyond reach. It is no coincidence that the eight $1 billion-plus privatizations to which 2017 has born witness include three of Asia's five largest non-infrastructure buyouts by enterprise value: Toshiba Memory Corporation at $18 billion, Global Logistics Properties (GLP) at $11.5 billion, and Belle International at $6.8 billion.

"The large end of the market has definitely expanded and really come into its own in the last five years," says Jean Eric Salata, CEO of Baring Asia. "Part of it is circular in that you have larger funds, so they can go after larger deals and create opportunities. One category of deal you see more often are the take-privates – we've done three in the last year. Those deals oftentimes only get done because there's an investor that wants to do them. The companies are usually not necessarily for sale."

Growth play

Even if larger fund sizes are facilitating more take-private transactions, it's just one aspect of a PE landscape that is inexorably expanding. GDP growth in Asia is around 5% per year, largely driven by industrialization, urbanization and rising disposable incomes in emerging economies. Compound that over five years and it represents a 30% expansion of the market. Needless to say, the companies that feed, clothe, power and entertain people in these countries have grown as well.

Ten years ago, there were 107 Asia Pacific-headquartered companies in the Fortune Global 500, including 29 from China and Hong Kong. Now China and Hong Kong account for 109 of the 200 regional entrants on the list. This filters down to businesses at every level and it is accentuated in the high-growth segments that many PE investors target. A company that was available for an enterprise valuation of $500 million 10 years ago might have a $1 billion price tag slapped on it today.

Belle International is an interesting example. CDH Investments participated and Morgan Stanley Private Equity Asia (MSPEA) took a minority interest in the business at a valuation of $370 million in 2005, when it had fewer than 2,000 outlets and posted RMB1.7 billion ($260 million) in revenue. By the time Belle listed in Hong Kong two years later with a market capitalization of $6.5 billion, the store network had doubled and revenue had more than tripled.

The company now has more than 20,000 outlets and generates RMB40 billion in revenue, although its valuation has taken a hit due to weak business performance – a decline that CDH and Hillhouse Capital hope to arrest now they have it under private ownership. CDH exited Belle several years ago but one of its founding partners remained on the board and helped engineer this year's buyout. The GP contributed around $400 million in equity, including co-investment, for an 11.9% stake.

"Our main fund is $2.5 billion so the team looks for $100 million-plus deals and we have a smaller fund for $30-50 million growth deals," says Stuart Schonberger, a managing director at CDH. "The move towards control transactions means larger ticket sizes. In a slower growth environment you want to have control and leverage, with a lot more predictability in terms of returns. But to do these large transactions with pure Chinese companies, relationships with management teams are critical."

"When I first started, buyouts were in Australia, Singapore and Hong Kong, with some activity in Korea. Now Japan is a large buyout market with conglomerates actively looking to carve out assets", says Ming Lu, head of Asian private equity at KKR. "When you look at China and India, buyouts are also a consistent part of the deal flow with the ability to deploy larger check sizes. Chinese and Indian companies are growing faster, as well, so those markets are really contributing."

Japan is indeed a blossoming large-cap buyout market. Seven deals of $1 billion or more have been announced since the start of 2016, as many as in the previous six years combined. Five of them are corporate divestments, motivated by a combination of governance reforms and an emphasis on return on equity and maintaining competitiveness.

But GPs must do more than just highlight how structural change in particular markets can contribute to greater deal flow when justifying a fund size increase. Any argument that a strategy is evolving to incorporate larger transactions would need to be supported by evidence of a few outsize deals in the previous fund – perhaps where co-investment was utilized – and a rapid pace of deployment for that vehicle. There must also be a pipeline of future deals that support the thesis and the development of internal resources to manage these larger undertakings.

"One of the most powerful arguments for growing fund size is performance," adds Javad Movsoumov, an executive director in the private funds group at UBS. "It's not the most logical argument because performance is driven by the types of deals you have done in the past. But if performance is good, that is indicative of you being a smart investor, and it drives demand for the fund. And the more demand, the more leeway a GP has on terms like the hard cap and fund size."

LP due diligence is intended to pick apart these stories. They will look at historic transactions by a GP in different geographies and sectors, how those investments have performed, and what or to whom that performance is attributable. "Nobody has a bullet-proof story in Asia," notes Doug Coulter, a partner at LGT Capital Partners. "Everyone has markets where they haven't done much or are looking to expand into because they are raising a larger fund and that's one way of justifying it."

Market by market

Almost every pan-Asian private equity firm has developed its footprint, adding offices in different markets, broadening sector coverage, and strengthening operational capabilities. With the possible exception of KKR, though, it is difficult to assemble profiles based on deal activity in the last four years that suggest true pan-regional as opposed to sub-regional coverage.

Some large-cap GPs target a more concentrated set of geographies, such as MBK with its North Asia buyout strategy that takes in Greater China, Japan and Korea, and Bain Capital, which has gradually extended its regional frontier with each fund. Others are more readily associated with certain markets based on actual or perceived frequency of activity: for example, Affinity and MBK in Korea, KKR and Bain in Japan, or PAG and Carlyle in China.

In this way, the notion of pan-regional firms competing on a level playing field where the only differentiator is their willingness to pay a premium in an auction process begins to crumble. Strengths and weaknesses are apparent on a sector basis as well, even though most private equity firms congregate around consumer-retail, financial services, healthcare, technology, media and telecom, and possibly industrials.

"Everyone has their themes and you know if a deal comes up in those areas they will have more latitude and leeway to focus on it, and they will be more aggressive," says Christopher Laskowski, head of Citi's global asset managers group in Asia Pacific. "They're selective about what they do and so these mega deals aren't that competitive. Homeplus [Tesco's Korea unit, which was bought by an MBK-led group in 2015] was an auction but it wasn't like you had 10 people competing."

At the extreme end of the spectrum, PAG faced no PE competition whatsoever when it paid $200 million last year for China-based kindergarten operator Golden Apple Education Group. Creditors had assumed control of the business because the parent company was in distress, which meant the GP had to engage in more than 600 negotiation sessions with 100 different groups. Shan attributes PAG's willingness to engage to its familiarity with banks and creditor processes in China.

Nevertheless, he believes that markets like China, where the level of trust is relatively low, will see less intermediation, with personal relationships and reputation coming to the fore. "If you don't know the people, then brand is a signal of quality," Shan says. "With a brand and a track record, you will get more than your fair share of the market. For new entrants, it is difficult. Even intermediaries won't want to work with you because they don't know if you will be able to close deals."

Establishing a presence in markets that do not display classic Western-style corporate characteristics like diverse ownership – unless a multinational is divesting an asset, that means everywhere in Asia apart from Australia – is therefore a protracted process. Success is largely predicated on an investment in people and this represents another obstacle to achieving pan-regional coverage.

Between 2005 and 2012, KKR invested $5 billion in Asia but only 6% of that went into Japan. Since the start of 2014, it has completed four buyouts in the country and has another pending, with about $2 billion in equity deployed, excluding co-investment. This uptick in activity can be tied to the success of one deal, Panasonic Healthcare, but also the accumulation of on-the-ground deal-sourcing and operational expertise.

KKR's stated aim is to make each local team among the leading players in its market and the firm is now looking to replicate elements of its Japan approach in Korea, where the GP is seen as trailing some of its regional peers. This involves bringing in people who can establish strong relationships with the chaebols, a rich source of potential carve-out deal flow but one that is generally difficult to access.

KKR made a breakthrough earlier this year, buying one business from LS Group and taking a minority stake in the company's larger auto parts subsidiary. But holding on to the people required to establish and maintain a position of strength in every market is difficult. While it did little to impede fundraising, KKR launched its third pan-Asian vehicle with relatively new replacements for China private equity heads David Liu and Julian Wolhardt, who left last year to start their own firm.

"The biggest roadblock for large buyout firms catering to a truly pan-regional market is actually balance of talent across offices," says Unigestion's Marchand. "Can one manager claim to have the best talent available for each country on its roster? Also, how long before the most talented individuals attempt to launch their own funds? These firms may have the capital and remit to invest across the entire region, but I think some understand it's hard to be good everywhere all the time."

Long term, short term

The top end of the market remains populated by roughly the same number of regional and global players, and opinion is divided as to whether it is sub-dividing as certain groups push past the $4 billion mark. However, most advisors attest that competition is rising for deals that involve check sizes of $100-500 million, particularly as the likes of sovereign wealth funds and Canadian pension funds participate directly in deals, either as part of GP-led consortiums or on a solo basis.

The long-term future of the pan-regionals does not appear in doubt. Though fund sizes in Asia are increasing, they have yet to match North America and Europe for scale. It is easy to envisage a future in which this gap closes, supported by a maturation of the corporate landscape as large-scale divestments and succession planning transactions become more common. On the GP side, sector specialization and the ability to manage deals from a global perspective will become more profound.

"Larger deals are just part of the evolution of the industry and fairly natural at that," says Andrew Thompson, head of Asia Pacific private equity at KPMG. "People look at fund sizes with a historical bias of what was big in the previous cycle. They questioned fund sizes in the last cycle but most GPs have comfortably managed to deploy the capital. The PE world is self-sorting itself into large platforms that offer multi strategies across many markets and more nimble country-focused funds."

However, the question preoccupying certain industry participants is more immediate: Is so much capital entering pan-regional funds that managers will no longer be able to efficiently address the private equity opportunity as it stands? This issue of size discipline applies not only to the funds but also to co-investment, and whether the pressure to deploy capital will push GPs outside of their comfort zones.

"A lot of co-investments are being offered to us at valuations in the range of 12-16x," says LGT's Coulter. "Each case is different – it might be a fantastic business and the growth rates are spectacular – but in general valuations have been creeping up and they continue to go up. No one can call a market top, but it feels a bit like 2007 again in some respects."

For several years, central banks have pumped liquidity into the global economy through low interest rates and other stimulus policies. This has provided an abundance of cheap debt for leveraged buyouts, and acquisition multiples have risen as a result. Public markets have also been on a roll, pushing up the valuations of companies against which privately-held businesses are benchmarked and creating a denominator effect as LPs find their PE allocations are comparatively underweight.

All these factors work in favor of increasing commitments to private equity funds and escalating valuations at the top end of the market. But the music could easily peter out. A public markets correction would curb investor enthusiasm while an economic downturn would usher in a period of readjustment. Citi's Laskowski notes that some of his clients are already pricing deals in the expectation of multiple contraction.

Any shock to the system would challenge the bullishness with which some investors have approached the market, stripping layers of expectation off deals to expose the fundamentals. "The only way to go about this is to have abilities and strategies for running businesses better than they are currently being run," says Baring's Salata. "That private equity formula works throughout the cycle at times of high valuations and low valuations.

SIDEBAR: Local takes on large-cap deal flow

Japan

Kazushige Kobayashi, managing director, Capital Dynamics

"Until recently, the number of corporate carve-out deals in Japan was limited and buyouts were dominated by small family succession deals. We continue to see those small transactions, but in addition to that, more large companies are now selling assets. We could see 10 deals a year of more than $100 million from now on. Public companies have to run auction processes, but these tend to be limited auctions and GPs have good chance to win if they have ‘edges.' The nature of the buyer is very important and GPs should be able to show value-add capabilities. Large deals are competitive and pricing tends to be high. While GPs can deploy capital, it remains to be seen if they can make good returns."

Australia

Tim Sims, managing director, Pacific Equity Partners

"Australia has hovered around the mid to high 30s in terms of percentage share of leveraged buyouts in the region, so it's hard to complete a pan-Asian fund without doing a deal in Australia or New Zealand. The issue traditionally has been that these funds are of such scale they need to target companies of $1 billion or more in enterprise value. These don't come up for sale that frequently, and when they do, they are generally auctioned and very well known. They also tend to be high fixed-cost businesses and therefore very cycle-sensitive. We do see some firms going down market in terms of scale, but they aren't necessarily competing directly with local managers."

Korea

Scott Hahn, CEO, Hahn & Company

"The largest companies in Korea are owned by chaebols, and there is not a consistent existing track record of foreign pan-Asian buyout firms doing buyouts in Korea, particularly among the chaebol groups. The biggest private equity acquisitions in Korea have involved foreign-owned companies. The largest chaebol deals have not been auctions – chaebols usually have specific people they wanted to sell to and it is usually to other Korean chaebols. The preference is for one-on-one negotiations or very limited auctions, largely due to concerns about confidentiality and related party concerns. The guys who have been doing buyout deals here will continue to do them. But it's not the easiest market to enter."

China

Stuart Schonberger, managing director, CDH Investments

"The move towards control transactions means larger ticket sizes. In a slower growth environment you want to have control and leverage, with a lot more predictability in terms of returns. What's interesting is that pure China plays – not overseas investments that relate to the China market – are still really created deals. Sometimes the role for private equity is not obvious and management teams aren't open to it because they don't think they need any help. Now the world has gotten tougher for everyone, there is more of a willingness to work with partners, but you still have to be flexible. And doing these large transactions, relationships with management teams are critical."

Southeast Asia

Nick Bloy, managing partner, Navis Capital Partners

""The pan-regional funds look at Southeast Asia more opportunistically – they are covering it, largely for fundraising purposes, but they know it won't be a big part of their portfolio. I've seen offices open and close in Singapore, but they seem more permanent now. However, I don't think that necessarily predicts a lot more deals being done in Southeast Asia because the check sizes aren't so attractive to them. They will see the occasional big deal because these transactions tend to be intermediated and heavily contested. The jury is really out on how returns will be affected by all of this. As long as they are prepared to pay high prices for some of my portfolio companies, I'm pretty happy.."

SIDEBAR: Auctions - In it to win it

When Newbridge Capital was negotiating to buy Korea First Bank (KFB) in the wake of the Asian financial crisis, it went into every meeting with a playbook. TPG Capital was one of the GP's backers and David Bonderman had previously initiated the successful turnaround of one of America's largest savings and loan associations. Newbridge wanted to take a similar approach with KFB. It was a hard-won battle, but KFB then became a calling card that opened up other financial services deals across the region.

Fast forward 15 years and KKR is going into meetings with Japanese conglomerates carrying a playbook of its own. In 2013, the GP firm acquired Panasonic Healthcare for JPY165 billion ($1.67 billion), telling Panasonic – which retained a 20% stake – that it could drive expansion domestically and overseas. Since then the business has doubled in size, in part due to the purchase of Bayer's diabetes care business. Last year, Mitsui & Co. invested at a valuation of JPY245.9 billion, enabling KKR to make a partial exit.

"We have exceeded many expectations with the company, and it is a reference point in every other meeting on the topic of carve-outs and our cross-border capabilities," says Ming Lu, head of Asian private equity at KKR. "Japanese companies know we worked with all the stakeholders at Panasonic Healthcare to grow this business, and those stakeholders have now seen the value-add beyond capital that we bring and are advocates of our partnership model."

Private equity firms have agreed five carve-outs from Japanese conglomerates in the past 12 months. Each was a competitive process and KKR prevailed in three – which suggests the GP is either willing to pay more for assets than its rivals or that auctions are won on more than just price.

"Most great private equity returns come back to buying at the right time, which is a skill with an element of luck, but most commonly because you've done something very well in terms of strategic or operational management," says Andrew Thompson, head of Asia Pacific private equity at KPMG. " That is not generic across every PE bidder - each firm has its own differentiated capabilities and takes a different approach to value creation. That's why there is a competitive buyout industry."

If a GP cannot preempt an auction, there are various ways in which it can differentiate itself from other bidders, beyond writing the biggest check. Most sellers prioritize certainty, speed and terms and conditions – they don't want to see a process held up by regulatory objections or financing difficulties.

In markets like Japan, much can be achieved long before the first round bids are submitted. Most GPs form relationships with local conglomerates in the expectation of future divestments. Detailed presentations are made covering everything from transaction structure to global expansion options to environment, social and governance (ESG) issues. The objective is to establish themselves as credible potential bidders.

Once a formal process begins, the onus is on understanding the target and conveying a credible post-acquisition strategy. Jim Verbeeten, a partner with Bain & Company, notes that some GPs are assertive in the first round, finding industry experts and signing them up as advisors. They are willing to accept the possible broken deal cost if it prevents others from accessing that expertise.

"Auction processes make up a large part of the market and you've got to sharpen your pencil and be competitive," adds Jean Eric Salata, CEO of Baring Private Equity Asia. "At the end of the day, people in our industry are disciplined. We all have the same pressure to deliver returns so there is a range of limits, pricing, that can work on a deal. It's a question of how aggressive you want to be within that range and what you do with the business post-investment."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.