Private debt: Feet on the ground

Investors see growing opportunity in Asian credit, but the region has proven difficult for foreign managers to address. Local expertise, particularly in emerging markets, can unlock the best returns

When Shoreline Capital Partners launched in 2004, the firm thought it had hit on a sound strategy. In partnership with a large US institutional investor, it would acquire portfolios of Chinese non-performing loans (NPLs), combining its on-the-ground market expertise with its partner's depth of capital. Flaws in this deal quickly emerged. Notably, Shoreline found its response time slowed at critical moments by the need to consult and gain approval from its US partner.

"We were sending packets of signature pages across the Pacific every time we needed to exit a loan," says Benjamin Fanger, co-founder of Shoreline. "They had to translate it into English, get a notarization from the Chinese consulate, and send it back – to say nothing of whether their judgment on something was correct."

The experience taught Fanger a fundamental truth about private credit. A foreign player like Shoreline's partner might see the asset class as basically identical to private equity, where an offshore fund manager can retain control over its local partner and still expect good returns. However, the shorter loan terms and hands-on management required in credit mean that a local operator attached to an outside firm will never achieve sufficient flexibility to stand out in the market.

"No matter how good the local partner is, unless you give them complete discretion, you're going to be sacrificing the best decision being made and also speed to exit," says Fanger, who left Shoreline last year to found distressed debt specialist ShoreVest Capital Partners.

This warning echoes a common sentiment across Asia's credit fund managers. Despite the excitement around certain markets or asset classes, investing in the asset class involves a number of pitfalls that can ensnare investors. Local knowledge and sector expertise is key to unlocking the credit opportunity.

Uneven allocations

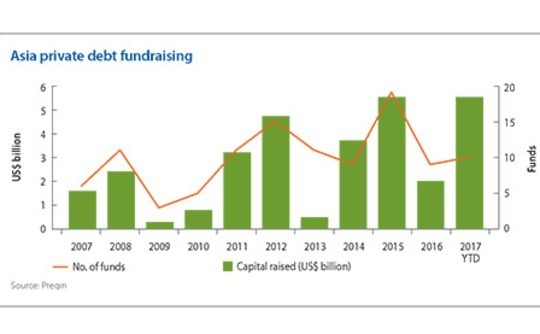

Allocations to private debt in Asia have been volatile, with large swings in both the amount of capital raised and the number of funds backed in the last 10 years. These variations are not always matched. While Preqin data show both the number of funds and the capital raised rose at roughly the same rate from 2009 to 2012, the decline the following year was much sharper on the capital side – falling from $4.7 billion to $500 million, while the number of funds dropped from 15 to 11. The number of funds fell again in 2014 to nine, while capital bounced back to $3.7 billion.

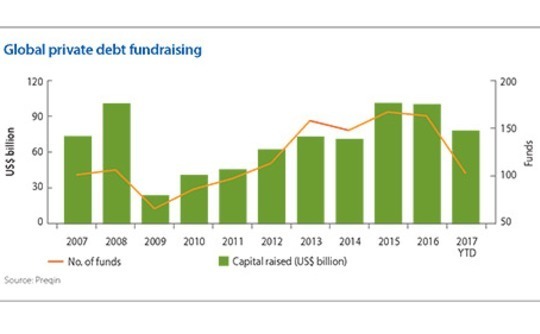

Meanwhile, global fundraising has been much more sedate. Following the global financial crisis, funds backed and capital raised hit a low of 66 and $23.6 billion respectively. Both steadily climbed over the following seven years, with $99.1 billion committed to 162 funds last year. To date, 2017 has seen $77.5 billion raised across 103 funds.

The disparity has not gone unnoticed among Asia's credit managers, who see it reflecting ambivalence toward the asset class on the part of LPs. The investors tend to agree, though they see the issue not in terms of resistance to credit itself; rather, it concerns the availability of trusted places to invest their money.

The shortage of established credit players in Asia is not disputed. However, many operators active in the region believe this phenomenon actually contributes to their ability to deliver good returns to investors. With the growth still occurring in the region creating a clear ongoing need for debt, many managers see the opportunity in Asian private credit as too enticing for LPs to ignore.

"If you compare it to Europe or the US, there are fewer people here with established restructuring skills. So we've seen pricing in this market sustain at more interesting levels than it has been in other markets," says Ilfryn Carstairs, a partner and co-CIO at Värde Partners. "As a general matter, the Asian credit space is a place where you've seen markets re-lever rather than de-lever, and you've seen that in both traded credit markets, high-yield markets, and private debt markets."

Nevertheless, Asian credit remains too big for all but the largest investors to consider tackling on a pan-regional basis. For the most part, managers that have achieved success have done so by focusing on one or two markets where they feel most qualified to address the particular credit gap.

Each Asian market is different, and may react to the same external force in different ways. For instance, the withdrawal of banks from lending to certain market segments due to capital requirements and risk weighting imposed by the Basel III framework has opened up new private lending opportunities in developed markets such as Australia.

In China and India, meanwhile, financial system inefficiency is the key driving factor. These markets share many characteristics, most prominently a massive and still-growing middle class quickly discovering a desire for consumer goods and convenience. However, traditional banks have failed to adapt to the needs of their booming economies, creating a shortfall in lending, especially to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

"These are markets that we find compelling, on the one hand, due to the inefficiency and the need for alternative capital, and they're also markets where it's have or have not," says Edwin Wong, managing partner and CIO at SSG Capital Partners, a spin-out of Lehman Brothers' Asia special situations business that mainly focuses on China and India. "The barriers to entry in these markets are relatively high, whether it's from an information standpoint or an infrastructure standpoint."

Baring Private Equity Asia found India so enticing that when the firm launched its credit unit, BPEA Credit, it decided that initially it would focus entirely on the country. It was attracted by India's relatively low levels of debt compared to other markets – domestic credit comprises 50% of the country's GDP, compared to 157% for China and 193% for the US – and the fact that most of that lending went to the government and large corporations, leading little for the middle market. Capital needs by mid-market companies had traditionally been filled by minority growth equity investors, but Baring believed debt would be an attractive alternative when companies realized it did not require equity dilution.

"The biggest attraction of India was the premium that we can achieve for the same level of risk relative to other markets," says Jean Eric Salata, CEO of Baring Asia. "In India we're able to lock in a contractual 16-20% return as a senior secured lender, with the bulk of that return coming from quarterly coupons. Even with a small amount of currency depreciation, those returns are still meaningfully higher than what we see in most other Asian markets for that kind of structure and level of risk."

Since establishing its credit branch in 2011, BPEA has seen the move rewarded: the firm says it has never recorded a loss in its credit funds, and the lowest return on any investment has been 18%. Moreover, as the country's credit infrastructure has improved in recent years early entrants like BPEA have received the benefits.

"To some extent, the market has really come of age, and certain developments, such as the establishment of credit bureaus, have been such a big game changer," says Kanchan Jain, a managing director at BPEA Credit. "In the last 10 years I've not seen the information flow and information sharing between lenders to be as good as it is now, and that's been a significant enabler in terms of looking at the credit opportunity in India."

NPLs and the rest

In China, the credit story has in recent years focused on NPLs. These assets, sold off in several waves following the credit-fueled response to the global financial crisis, have been acquired to some success by players such as Shoreline and ShoreVest which make use of their country knowledge and networks to turn around the affected companies. Pan-regional and global players such as Oaktree Capital Management, Bain Capital Credit, and PAG are also looking at the space with renewed interest.

However, there is also some skepticism about the NPL space despite its recent popularity. Doubts have centered around the fact that these loans must be filtered through China's government-backed asset management companies (AMCs) on the national and provincial level before being made available to investors, raising concerns that foreigners will only be able to access the lowest-quality loans.

"Distress and NPLs are very popular with investors lately, but these strategies make the least amount of sense in many ways," says Hamilton Lane's Delgado-Moreira. "Today the reality is that there's far more capital raised for NPLs and distressed investments in China than the opportunity has shown thus far, and it may never really prove to be a large opportunity."

For those that want to avoid NPLs, direct lending represents another way to access the credit market. China's middle market has been affected in similar ways as India by the aversion of banks, and private lenders, with more flexibility on capital reserves and risk weighting, along with country expertise, can find opportunities in places overlooked by traditional financial institutions.

"We find direct lending, particularly in less known second-tier cities and the like, as much better relative risk-adjusted returns," says Rob Petty, Managing Partner of Clearwater Capital Partners. "These million-person cities are really quite substantial, and particularly with the infrastructure growth in China, a lot more accessible to the overall Chinese economy."

There are factors that China-focused investors might have to weigh more heavily than those in other countries, however. Loans in China may have a political component with consequences not obvious at first. Managers that lend in sectors that the government has attempted to discourage might find it hard to get regulatory relief or assistance from the courts if the investments go bad.

"For example, now that the government has come down against the real estate bubble, developers are desperate for cash," says Barry Lau, managing partner at Adamas Asset Management. "On the other hand, investors don't want to go there, because the government could just as easily say I told you not to support that sector. If you supported them and they went bust, tough luck. I'm not helping you."

While developed markets may not offer the same growth prospects as emerging countries, the sophistication of their credit markets give them a particular appeal. Clearwater, which has been involved in Australia since 2009, has found the country to be a consistent source of good returns, particularly since Basel III prompted the major domestic banks to withdraw from corporate lending.

"We're not going to win on rates or weak structure, but when the banking system simply can't do a deal – maybe they're full on limits, or they're being more conservative on LTV – then, as is the case today, you can really structure some very thoughtful client-friendly deals that also are interesting from an underwriting and yield perspective," says Petty.

Some managers have attempted to address Southeast Asia, reasoning that the region is affected by the same pressures as China and India. However, most such attempts have been stymied by the fragmented nature of the markets, with multiple cultural, regulatory and legal divisions.

"There have been a small handful Southeast Asian credit plays, but they haven't really gone very far, says Vincent Ng, a partner at placement agent Atlantic Pacific Capital. "It's a nice notion, but trying to source direct lending or mezzanine or other credit deals in each of these markets is very different. The local networks are very different, and so is the local legal structure."

Learning process

The need for local expertise unites the region's credit players, particularly those like Värde, which established its Singapore headquarters in 2008. The firm considers it vital to build up an understanding of the markets where it seeks to invest, and often does so through joint ventures with local players. Altico, its India non-banking financial company (NBFC), is one example, as is Latitude Financial Services, the former consumer finance business of GE Capital that it bought alongside KKR and Deutsche Bank.

"Our first question before going into any more difficult market is, have we established the right to play?" says Värde's Carstairs. "Have we got people on staff who really understand how to do business in those markets, do they speak the languages, have they done business in those jurisdictions? You can show me opportunities in certain markets that look very compelling, but we may not have the right to play in them."

But even as managers agree on the importance of understanding specific markets, they also feel that Asia's credit opportunity has only just begun. Lenders that can keep an eye on the global situation as well as the local economy will have an edge as the world becomes more and more connected.

"There's a whole business around some of the biggest companies in Asia that shouldn't be bucketed geographically," says Clearwater's Petty. "You may come to Hong Kong and finance a Chinese business, but the asset you're financing is in the US or Europe, or is floating off the coast of Australia. There's a lot more going on in the pan-Asia business than just the single-country opportunities - there are large deals with big companies across the pan-Asia space."

SIDEBAR: China - The NPL opportunity

As Benjamin Fanger, a co-founder of distressed debt specialist Shoreline Capital Partners, sat down to lunch with a member of the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) in January 2015, the country's lenders had just begun their latest wave of non-performing loan (NPL) sell-offs. But unlike in the previous cycle in 2011, when the government established four asset management companies (AMCs) to absorb loans from the banks dollar-for-dollar, this time no such bailout was in the offing.

"I said, ‘So what are you going to do?' and he said, ‘We're going to let the market digest it,'" remembers Fanger. "And I answered, ‘What market? There is no market – there's Shoreline and four AMCs.' He said they know that – that's why they were going to do everything they could to encourage the market to grow, including improving the legal processes, reducing regulatory hurdles to people buying the NPLs, and pushing the banks not to hide their NPLs in off-balance-sheet transactions."

Fanger, who left Shoreline last year to found ShoreVest Capital Partners, says that promise has largely come to pass. Not only are banks marking down their trillions of dollars in NPLs to sell directly to third-party investors, but enforceability has become much less of a headache than in previous years, with courts showing increased willingness to hold borrowers to the terms of their agreements.

Other China-focused NPL specialists agree that the market has opened up – but they caution that this opening has created new challenges as well.

"A lot of new competitors, both foreign and local, are joining the market, and they've pushed transaction prices to a very high level," says Tony Liu, COO at Shoreline. "One of the Big Four banks released a Chinese NPL portfolio in the second quarter of this year where the average transaction price was $0.45 on the dollar, and the highest was $0.75. The NPL portfolios that we bought in 2015 averaged less than $0.30."

The changing nature of the loans has also fueled interest from outside investors. In previous years the loans available in the market included significant representation from state-owned enterprises (SOEs) – Fanger estimates in the last cycle 50% of Shoreline's NPLs came from SOEs. In this cycle, however, that figure has changed dramatically, with privately-owned borrowers representing more than 90% of Shoreline and ShoreVest's purchases. Foreign investors have found these loans more enticing due to the perception that resolving SOE debt is more difficult than that of private borrowers.

Market participants believe this inflationary tendency is not likely to last beyond next year. Once the initial flurry of investment activity gives way to the need for active portfolio management on the part of buyers, demand and pricing for loans are expected to be reduced to a more reasonable level. But investors will likely remain attracted to a market where the NPL opportunity is big enough to outweigh any other market in the region.

"China NPLs and distress are big enough to be a single investment market for a manager," says Liu. "So those investors that are more familiar with China recognize it's a huge opportunity – it's just a question of timing."

SIDEBAR: India - NBFCs in the spotlight

The rise of non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) in India has presented a unique opportunity for private equity firms. These businesses offer an inroad to the country's small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which have historically found it hard to obtain financing from traditional banks.

"It's not formally delineated, but I would say there are complementary pools where the banks and NBFCs can play, and continue to grow quite attractively over the coming years," says Dhanpal Jhaveri, managing partner for private equity at The Everstone Group.

Everstone is one of several PE investors that have established their own NBFCs – IndoStar Capital Finance, the firm founded by the GP in 2011, focuses on wholesale secured lending for corporates. Other players in the space include KKR, which has launched several NBFCs in the country, and Värde Partners, which founded Altico Capital India with special situations investor Clearwater in 2004.

But the expansion of NBFCs has drawn attention from the country's financial regulators, principally the Reserve Bank of India. As a result, the institutions face growing pressure aimed at reducing the risk they pose to the financial system. "Because the regulators have started to see them as posing similar kinds of systemic risk, the supervision has become closer over the years, with annual audits and similar kinds of restrictions to what banks have," says Kanchan Jain, a managing director at Baring Private Equity Asia.

This does not mean that the NBFC model itself is in doubt: these institutions are still better suited to meeting the financing needs of India's SMEs than the country's public or private banks. This means the banks themselves do not see NBFCs as competition – in fact, the industry is quite lucrative for traditional financial institutions, which are typically the NBFCs' main source of capital.

However, as regulators increasingly tighten their hold on NBFCs in recognition of their importance, investors need to be prepared for the institutions' profit margins to shrink due to compliance costs, and the NBFCs may need to change their strategies if they want to make consistent returns.

"I think they'll remain an important part of the lending side and they'll grow in market share, but they have to adapt themselves if they have to target the more structured transactions, because the areas where they've succeeded have been the more vanilla, volume-driven granular asset classes, as opposed to the more structured debt deals," Jain says.

SIDEBAR: Australia - Unleashing the unitranche

With Australia's banks withdrawing from the corporate lending space due to growing capital adequacy requirements, private lenders are stepping in to fill the gap in the transaction financing market. Some of the larger players have taken the opportunity to introduce a structure first tested in Europe and the US: the unitranche facility.

These vehicles, which combine senior and mezzanine facilities into a single structure, have suffered somewhat from misplaced expectations, according to industry players. Borrowers who expect a significant savings due to the combination of mezzanine and senior debt may be disappointed – the real advantage is in the simplification of the deal terms.

"You probably end up roughly where you would have ended up with a classic two-layered structure," says Ryan Shelswell, head of Australia for equity and mezzanine at Intermediate Capital Group (ICG). "But if you can get a single piece of debt and deal with a single lender or maybe one or two lenders, that would be easier than two syndicates or one syndicate plus a mezzanine lender."

The unitranche facility has proved attractive and allowed major non-bank lenders like ICG, KKR Credit, Bain Capital Credit and Partners Group to grow their shares of the private lending market. For smaller players, the effect has been less pronounced – in part because the structures tend to be significantly larger than a typical mezzanine lender can provide.

"It's been talked up as if it's going to change the middle market," says Nathan Cahill, a partner at MinterEllison. "But we have a lot of clients in that space, and what we see is a lot of the money that's being spent is not unitranche at all – it's just vanilla, senior syndicated loans, bilateral arrangements."

This concern can be addressed somewhat through arrangements that allow multiple players to provide part of a larger unitranche structure, but this means smaller lenders must rely on the ultimate owner of the unitranche to enforce the deal.

Additional doubts exist around the novelty of the structure – though it was introduced in 2005 in the US and 2008 in Europe, lenders in Australia have largely only gained exposure to unitranche in the past year. Adoption is likely to be limited until lenders familiarize themselves with the possibilities of the structure, and learn to guard against its dangers.

"Every time people propose a new product in financial markets, if you've been around for a while you always wonder what happens when one of those blows up," says ICG's Shelswell. "We all hope that won't happen, but eventually one does, and it'll be interesting to see how people restructure a unitranche facility."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.