One Belt One Road: Probationary bonanza

China’s One Belt One Road agenda is set to be a driving force in M&A activity that reshapes economies across Eurasia for decades to come. Early movers are consequently negotiating a new world of variables

M&A deal makers do not typically consider Albania a key gateway to Europe. But as China's One Belt One Road (OBOR) policy comes increasingly into focus, this might be one of many areas of conventional wisdom to get turned on its head.

State-backed financial conglomerate China Everbright helped illustrate this point with its acquisition of the main airport in Albania's investment-hungry capital of Tirana. Due diligence work for the deal dates back to 2015, when OBOR was beginning to influence decision making but capital pools targeted specifically at the initiative were still getting in gear.

The investment is squarely in line with the OBOR vision, but none of the initiative's rapidly growing policy banks are involved. Everbright bought 100% of the airport under its Overseas Infrastructure Fund, which is targeting $1 billion and reached a first close of $300 million in July. The firm aims to increase Chinese travel to Albania through Italy and Greece-connected tour packages and has already begun parallel talks with local government about industrial works such as water treatment, logistics and manufacturing facilities.

"We were looking purely at the project fundamentals and merits, but the upside of Belt & Road was part of the base case because we expect it to bring more people to the airport and there will be more business activity with Chinese companies in Albania," says Daniel Hu, a managing director at Everbright. "If the deal were done today, the expectations would be different. I'm not saying that the terms would be different, but the process would be more difficult because there has been a change in psychology."

This new psychology is a cocktail of policy-driven investor confidence fueling increased competition for assets combined with concerns about deal mechanics, alignment of interest, and the inherent economic questionability of projects propped up by government funds. The notion that M&A opportunities connected to China will increase is practically unanimous, but the new opportunities will not necessarily be approachable with traditional deal sourcing instincts.

Expansion agenda

OBOR is reimagining China's Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road as a multi-continental infrastructure modernization plan that will cost some $5 trillion in the next five years. The key difference from historical attempts by Western entities to build up Eurasia's developing nations is the geopolitical context.

This time, China, a developing nation in its own right, will not be measuring success of the overall vision by calculating the financial outcomes of individual projects. As a natural extension of the growth story of the world's largest country, the policy is widely expected to help bring three billion people into the middle class and account for as much as 80% of global GDP growth by 2050. Indeed, OBOR talking points tend to have a ring of destiny among politicians, analysts and investors alike.

The fact that the Chinese government is pushing hard for OBOR while simultaneously reining in outbound M&A activity is a telling clue that money is not the only factor at play. While Chinese buyouts of trophy assets such as European football clubs get put on hold, OBOR's more socially conscious statecraft is aggressively supported. The latest M&A guidance issued by Beijing referenced the policy heavily under its "encouraged outbound investments" section.

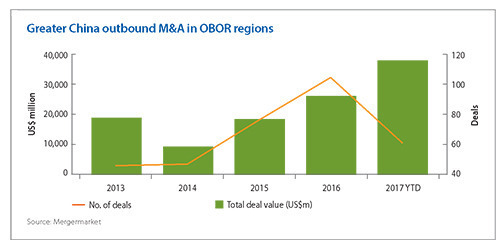

Greater China outbound deal flow in OBOR regions in recent months has consequently bucked the trend of the broader M&A market. According to Mergermarket, China outbound activity is down significantly this year, totaling $96.2 billion across 258 deals in the first three quarters, versus $204.1 billion across 384 deals for the whole of 2016. By contrast, Chinese M&A in OBOR regions has increased during the same period, from 104 deals worth $25.9 billion in 2016 to 61 deals worth $37.5 billion so far this year.

Although no glaring outliers are believed to distort this statistical trend, there remains some skepticism about the assumed causality behind the schism. Hilary Lau, a partner at Herbert Smith Freehills (HSF), for example, says that the uptick in buyout activity in OBOR regions may represent more than just a direct reflection of the policy since most of the relevant OBOR investments are in greenfield development and therefore do not qualify as purely M&A.

"We see a lot of interest, but in terms of actual investments, it's been slow generally," says Lau. "I think it's because so much of it is still unclear – who's behind these projects, what are the economics, and the fact that these are greenfield projects which nobody has really done before. Therefore, one of the considerations is nobody wants to be the first company to be doing some of this stuff."

If Western investors embrace the greenfield risk under OBOR in large numbers, it would represent a major shift in philosophy about investment in Asia, where more mature businesses are historically the preferred targets. Optimism about this possible evolution is related to the idea that OBOR is both a nebulous international trade concept and a centrally controlled directive of the Chinese government.

Due to this dual nature, M&A activity under OBOR has not been curtailed like other China outbound deal flow. Indeed, a number of government concessions are being implemented to spur acquisitions by state-backed policy vehicles such as the Silk Road Fund, which is now said to be exempt from applying for approval from the National Development & Reform Commission.

Heating up

The scope of near-term M&A activity is therefore expected to hinge largely on the decisions of China's Communist Party national congress later this month. "If capital controls are eased in the future and the Western world does not relax its hurdles for Chinese M&A, there will be fewer deals chased by a lot more money," explains Patrick Yip, Deloitte's national M&A leader for China. "Belt & Road projects may become attractive to investors who did not see them as that attractive before."

The envisaged increase in competition will bring with it a sharper focus on uncertainties around OBOR's looser aspects, including how to establish meaningful project valuations and identify deal pipeline channels. The latter of these challenges is already being amplified by a general lack of deal publicity – despite OBOR's buzzword status.

"It's not the usual M&A scenario where you get a bank to find some buyers and do an auction – it's a very different way of selling M&A," says HSF's Lau. "A lot of investors come to us asking where and what the Belt & Road projects are, but there's not a lot of clarity about that, and people are grappling with it."

Deal sourcing in this environment will require closer contact with the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) involved as well as state-backed financial institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, China Development Bank, China Investment Corporation, and Export-Import Bank of China (Chexim). Industrial partnerships with the likes of the China Petroleum Pipeline Bureau and the China Machinery Engineering Corporation will also be advised depending on asset particulars.

CEE Equity offers the investment industry an early example of how to bring these strategies together into a specialized OBOR vehicle. The eastern Europe-focused firm raised $435 million for its debut China cross-border fund with support from Chexim, while its second vehicle is expected to close this year with Silk Road as an investor.

"At the top level, we really see our very existence coming from the Belt & Road initiative," says Bill Fawkner-Corbett, an investment director at CEE. "We look at hard infrastructure but for us, there's also a soft element to it related to trading with China. Some of our investments may not have a strong connection to Belt & Road, except when we come to sell them, we think that Chinese and strategic companies might be natural buyers."

In a way, this enhancement of future divestment potential ¬– which likewise colored Everbright's Tirana airport decision ¬– represents OBOR's environmental effect. As an economic movement based on essential infrastructure, it inherently implies the creation of more investable jurisdictions within a 5-10 year turnaround time.

As this evolution unfolds, other influences on deal flow will include the added due diligence consideration that comes with strong government favoritism. Although industry participants confirm that M&A proposals are not being packaged differently as a result of OBOR hype, investors are arguably under increased pressure to balance the positives of stable government backing with the negatives of development motivated by politics rather than generating returns.

Playing piggyback

This dilemma complicates the financing bottleneck of OBOR, which is said to have mobilized only about $200 billion so far – well below the trillions projected to be needed. Private investment is therefore seen as a critical adjunct to the current government-driven action and likely to be further encouraged in the years to come.

NDE Capital, a Chinese private equity firm that works with SOEs and other state actors to fill supply gaps in soft infrastructure, has tracked a distinct increase in investor appetite for OBOR-related M&A. "In the past nine months, we have seen an influx of LP requests about Belt & Road because they don't want to miss this boat," says John Lin, a partner at NDE. "Consumer is still the starting point of what we do, but the thematic patterns have changed a lot."

The firm's strategy reflects a number of core expectations about how M&A will develop across OBOR's various industrial and geographic angles, including a focus on healthcare and the South Asia-Indochina corridor. "Belt & Road is big in China, but in Southeast Asia and other parts of Asia, they don't really understand what it means, so the question is how do we tie it in to consumers and the modernization of the Chinese economy," adds Lin. "You have to connect the dots to make the ecosystem real."

Other areas tipped to see increased M&A include corridors connecting Europe with the Middle East, and China with Pakistan and East Africa, as well as transcontinental bridges over Central Asia and Russia. Across these zones, the maritime routes denoted by the "road" are expected to take an early development lead versus the overland "belt".

CITIC Capital seems to be echoing this consensus with an expansion of its OBOR mandate from a traditional focus on Central Asia to include more Southeast Asian opportunities. The firm is looking to raise up to $600 million for this plan, but stresses that geography is not the name of the game.

"We are not hung up on the domicile of companies because in a global world, I'm not sure this is the most befitting approach," says Fanglu Wang, a managing partner for the CITIC Capital Silk Road Fund. "The Belt & Road concept is big, but we are actually operating in an even bigger theater, aiming to source technology and products from outside the region to create synergies with the target markets, as repeatedly demonstrated by our closed deals."

An emphasis on business revenue sourcing across multiple markets can be seen in CITIC Silk Road's portfolio mix, with investments split about 20% in China, 70% in other OBOR countries and 10% across the rest of the world. Sectors of interest include transport, logistics, energy generation and related utilities, as well as food and water safety.

With this strategy, much of the uncertainty swirling around M&A under OBOR can be contextualized in more familiar terms. While concerns around the initiative's status as a policy-driven greenfield program raise questions about how to find the right inroads, a certain clarity can be discerned by remaining focused on the established modernization themes of the developing world.

"We've seen deal flow pick up, and part of that is due to awareness of Belt & Road, but I think it has more to do with our reputation, experience and networks," says CITIC's Wang. "We're seeing a lot of activity in the mid-market, especially in environmental, social and governance-related sectors, but our investment decisions are ultimately based on the returns. It's a global trend where China is gradually taking a leading role worldwide, so it's no surprise that it's happening in the Belt & Road regions as well."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.