Moving time: How VCs replace start-up CEOs

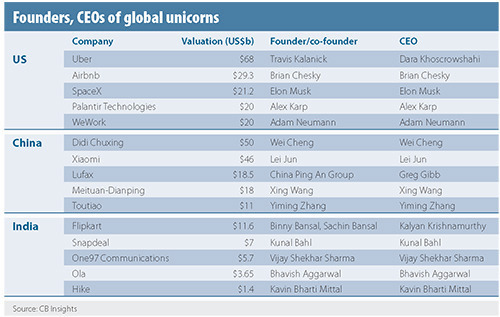

From Uber to Flipkart, there are high-profile examples of founders being replaced as CEOs of their start-ups. It isn’t common practice in Asia, and for reasons of corporate culture, this isn’t likely to change

Benchmark Capital's move to file a lawsuit against Uber founder Travis Kalanick early last month surprised many industry watchers. It's not a norm for a well-regarded Silicon Valley VC firm to sue a fellow board member and the founder of one of its most valuable investments.

Kalanick had resigned as Uber CEO in June following a series of controversies including allegations of sexual harassment by his employees and the use of software designed to bypass regulators. Benchmark further alleged that Kalanick had committed fraud, breach of contract and breach of fiduciary duty while trying to maintain control over the company. The GP wanted to remove him from the board and eliminate the three additional voting directors he sought to introduce last year.

Uber's boardroom brawl then became even messier as a group of Kalanick-supporting investors rallied against Benchmark and called on the firm to offload its shares. The mud-slinging has now abated with the appointment of former Expedia boss Dara Khoscrowshahi as CEO of Uber and a court ruling – in Kalanick's favor – that the Benchmark suit should be moved to arbitration, thereby avoiding a public battle.

The situation is unusual given the venture capital industry traditionally advocates constructive relations between founders and investors. But CEO replacement does happen, albeit more frequently in the US than in Asia. Kalanick's grip on Uber notwithstanding, the cult of personality around founder-CEOs is stronger in China and India than in Western markets, which means it is harder to bring in a new leader. Furthermore, Asia's technology talent pool is shallower than that of the US, so a suitably qualified replacement CEO isn't necessarily available.

"I think it is culturally less acceptable to ask a Chinese founder-CEO to resign and bring in a replacement. The founder-CEO is typically the face of a company, and the venture idea is about investors picking the right entrepreneurs to back especially in the early stages. So far, I have not seen or heard any GP complaining out loud about changing their founder-CEOs in China," says Jireh Li, chief representative for Asia at US-based fund-of-funds Commonfund Capital.

Pivot point

The key facets of venture capital value-add are well established, and human resources is one of them. Start-ups often need help in the early stages to recruit individuals – such as CFOs, CTOs and marketing specialists – who can fill out the executive team and pursue scale at speed.

However, the founder-CEO is usually untouchable, especially if a start-up is well-run. Industry participants in China and India note that it is rare for these individuals to be asked to stand aside in favor of a professional CEO – and it inevitably happens when a company is operationally flawed or falling behind its growth trajectory. VCs have in the past decided to write off an investment rather than damage their relationship with the founder by suggesting a replacement.

"We don't get into an investment with the mindset of replacing the founder-CEOs at some point. We enter with the expectation that the CEOs we back are going to create businesses of significant size," says Richard Lim, a managing partner at China-based GSR Ventures. "That's the assumption we make – we are funding the person as much as we are funding the business."

The situation is somewhat different when a venture capital firm incubates a start-up. The investor is building the business – sometimes seeding it with technology as well as capital – from the ground up and in due course hires a professional CEO. But they do this from a position of strength: they typically have a lot of power at board level. For VC firms that invest in start-ups that have been independently founded, CEO replacement is challenging, particularly after the Series B round. If changes are to be made, they must happen early.

James Mi, a managing director at Lightspeed China Partners, recalls studying an early-stage online technology business and concluding that the founder-CEO was strong in product development but lacked the leadership skills to achieve scale. Over the course of several candid yet friendly conversations, the founder-CEO recognized his weakness and supported the idea of hiring an experienced hand. He took the initiative in identifying the right person, who then became a part of the founding team. Lightspeed invested and the company is now an industry leader.

"Changing the CEO is very difficult and usually doesn't work in China. In rare cases, it could work at an early stage. Early stage investors focus on the quality of the founding team, especially the CEO. If they sense the founder-CEO would be better as CTO, they should also know whether he would be open to an external hire. It's not easy, but if the original founder-CEO realizes and embraces that, it's possible. You can't force founder-CEOs to step down if they aren't willing to do so." says Mi.

Venture capital investors are seldom activists. They take minority stakes in start-ups and many are unwilling to have any operational involvement, citing the speed at which technology businesses typically grow. There is a desire to preserve an alignment of interest with the founder and they may raise issues with the hope of steering events in a particular direction, but in an ideal scenario the founder takes the initiative on major decisions like introducing a new CEO.

Chinese software outsourcing services provider HiSoft Technology International is a well-known case in point. Founded in 1996 by Yuanming Li, the company grew fast and built up a large multinational client base. After receiving Series A funding in 2004 from the likes of GGV Capital, Intel Capital and the International Finance Corporation, Li expressed doubts to one of the investors about his ability to take the company to the next level. He raised the possibility of hiring an external CEO.

"He is the founder and he needed to know what he wanted, because ultimately the company is his baby. I asked him if he wanted to see the baby to grow up. [Regarding an external CEO] I told him, ‘If that's the case, then we have to decide. You may want to change not only the crew but also the pilot,'" the investor recalls. "It took a long time to change the CEO. It was not easy."

The investor, who was also a board member, helped recruit Tiak Koon Loh, formerly a corporate vice president at Hewlett-Packard, as HiSoft's new CEO in 2006. This was followed by several other senior appointments, including a CFO and COO. The CFO reported directly to the board, not the CEO. HiSoft listed in the US in 2010 and subsequently merged with industry peer VanceInfo to form the company known today as Pactera.

"We have also seen some founders in India recognizing their limitations," adds Anand Prasanna, a managing partner at India-focused GP Iron Pillar Capital. "But, in many cases, it would take forever for them to really take action, like hiring an external CEO or other senior management to run the company."

In the rare situations where venture capital investors hold majority interests in companies, they can execute their shareholder rights to force out the founding team. This happened to one India-based technology company shortly after its Series B round, when the VC backers concluded that, although they liked the product, the founder-CEO wasn't the right fit to develop the business further.

"There was significant tension at the board level, and two parties were close to going to court. Eventually, things were amicably settled and the founding team left the business, but they still held 40% of the company," says Prasanna.

Cultural differences

Procrastination is generally more common than legal action. VC investors hold off raising the prospect of CEO replacement because they have developed close relationships with founders, and once a decision is made it takes time to implement.

One investor recalls a Chinese company struggling in its mid-stage rounds because the founder-CEO didn't follow board recommendations about changing the business strategy. The VC backers even went as far as to promise the founder-CEO they would re-up in the next round and find new investors to participate if he would step aside. Eventually, he grew tired of the battle and agreed to transition to a chairman role provided the investors could find a suitable replacement as CEO.

"Investors usually don't hold all the cards. It's kind of a symbiotic relationship between the founder and investors before the company goes public. While VCs need a strong founder-CEO to build a successful company, the founder also needs the investors' confidence and support to continue to attract capital. Once that relationship breaks down, whatever change VCs want to make, it's going to be traumatic for the company," says James Lu, a partner at law firm Cooley.

When investors lose faith in the founder it is often seen as an indication that the company isn't performing well. Finding a CEO who is able to assume management responsibility is difficult in relatively immature markets; finding one who is able and willing to take over a troublesome technology company is harder still. Many executives with experience of taking a company to IPO would prefer to launch their own start-up than be an employee at someone else's, albeit one that is well paid.

Asia and the US do not only differ in terms of the depth of their technology talent pools. Historically, the US venture capital industry has been very hands-on: Josh Lerner, a professor and head of the entrepreneurial management unit at Harvard Business School, was once told by a US-based VC investor that he had invested in 20 companies and fired the CEOs at 19 of them.

"Obviously, that's a very dramatic example. But it accurately conveys the message that the CEOs who were good founders running a company in its first couple of years aren't necessarily the best CEOs later-on for the company," Lerner says. "People like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg have been very successful in both founding companies and running them. But most founders are not like that. I think founders in the US usually realize that finding a replacement is part of the game."

In contrast, Asian founders look at their start-ups more as personal affiliates – often 90% of their personal net wealth is linked to these businesses – and the prospect of no longer being the leader would equate to no longer having a career. As such, a founder might try to make his or her position essentially inviolable by retaining the right to appoint the majority of board members.

Legal provisions are renegotiated with each funding round to ensure such power is retained. When a company reaches Series B or C, it is increasingly common for the founder-CEO to seek super voting rights in an effort to hold on to control of the company's voting shares because the round is so large that their equity is substantially diluted.

"In the absence of a new financing event, existing investors would typically resist amending the existing governance agreements to provide for such a change in voting control. However, if the new investors agree that the founder-CEO will have super voting rights, the new investors likely will want to ensure that existing investors do not end up with greater voting control per share than they have," says Thomas Chou, a partner at Morrison & Foerster. "This means that the implementation of super-voting for the founder-CEO often ends up applying to all series of preferred shares, rather than against only the newest series of shares to be issued."

In addition to board composition and voting shares, old and new stakeholders must also agree on certain protective provisions. Often, these provisions require that the appointment, removal or any material changes in the compensation of senior executives, such as the CFO and COO, must be approved by preferred shareholders or board directors. While these provisions give minority investors a right to block the removal or appointment of an executive, they often do not result in affirmative right of such investors to force through a removal of the executive, Chou explains.

The Uber situation does involve a power battle at board level. Benchmark – a significant minority shareholder with a board seat – opposed a decision last year to expand the number of voting directors from eight to 11, with Kalanick having the sole right to designate those additional seats. Indeed, after resigning as CEO, he could name himself to one of those seats. Benchmark argued that it wouldn't have supported this due to Kalanick's "gross mismanagement and other misconduct at Uber," which included pervasive gender discrimination and sexual harassment.

The subsequent division of the board into two groups with different alliances – as exemplified by the Kalanick backers calling on Benchmark to sell its shares – further complicated matters. "In Uber's case, there are some reputational costs [for Benchmark] of being an unfriendly VC. It's a messy situation and can lead to bad publicity. But if you've billions of dollars stake in the company, you might be willing to do that," observes Harvard's Lerner.

Dissenting voices

In some respects, this added complication is a result of Uber wanting to stay private for longer, raising substantial rounds of funding at ever higher valuations. The company's investor base is large and reflects a range of interests, which means discord is more likely to occur. This has also proved to be the case at a number of Asian unicorns, with conflicts of interest emerging due to the presence of groups that have different risk appetites and investment horizons.

Another characteristic of certain start-ups that have raised billions of dollars in private capital is that investors assume positions of influence – particularly if a company is losing direction – by virtue of the amount of money they have at stake. Flipkart, India's largest online retailer, is a good example. Tiger Global Management is the company's largest backer, with an approximately 35% stake, and earlier this year one of its former managing directors took over as CEO from co-founder Binny Bansal.

"It's very unusual in India to get the founder to be replaced. There are only certain circumstances that can lead to this – it could be a founder's personal decision, the company is in trouble, or there is a huge conflict within a founding team. But most VC investors don't want to force the founders out," says Ash Lilani, founding partner at India-focused Saama Capital.

Generally speaking, no venture capital firm wants to be known for removing founders because word spreads in the start-up community and it may struggle to secure the best investments. Given the less confrontational nature of Asian corporate culture, the cult of personality around founder-CEOs, and the limited supply of experienced executives, the reluctance to ship in replacement leadership at Chinese and Indian start-ups is understandable. It may become more frequent as the industry matures, but few market watchers flag it as a meaningful future trend.

"If you look the large tech companies in the world – Amazon, Facebook and Alibaba Group, as well as the last generation tech giants like Apple, Microsoft, Dell and Intel – many of them are run by the founders for a long period of time," says GSR's Lim. "The venture industry is about making the most money from large companies. Since most successful companies are operated by founders, I don't expect changing the founder-CEO to become the norm."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.