China dairy: Gone sour?

China’s dairy industry has experienced a dramatic fall from grace, driven by overhype at home and lower prices overseas. Investors that got in at the top of the market are considering their options

"The original site is empty now, it's a ghost town," says Berwick Settle, a New Zealander who used to be general manager of the farming operations at China-based Huaxia Dairy. Just three years earlier, the company was riding high, having secured $106 million in funding led by GIC Private and Olympus Capital Asia. It had 13,500 cows across three farms on the outskirts of Beijing – most of them at its home farm in Sanhe – and was in the process of building a fourth to serve the Shanghai market.

Huaxia earned a reputation for providing high-quality milk from high-tech facilities, but that 2014 investment marked a peak for the industry. As raw milk prices dropped below production costs, Huaxia started hemorrhaging money. In February, the business was sold to locally listed dairy company Saikexing for RMB607 million ($90 million) in shares and RMB13.6 million in cash. The Sanhe farm was part of the deal but didn't feature in the initial portion of assets transferred.

Olympus, which invested $108 million in Huaxia over the course of about four years and was the company's largest shareholder, retains an interest in the business through its stake in Saikexing. The private equity firm is understood to have marked down the investment to reflect the difficulties currently facing the industry and is working with Saikexing on a turnaround.

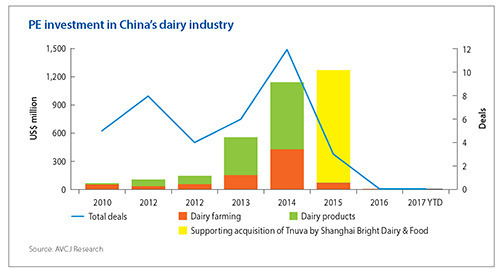

PE investors pumped nearly $900 million into Chinese dairy farming assets in 2013-2015, while the broader dairy products space received $1.1 billion, according to AVCJ Research. KKR and CDH Investments had already found success with China Modern Dairy and these new deals were underpinned by a similar thesis: consumers are willing to pay a premium for high-quality, safe products; and integrated dairy operations are the best way to create transparent supply chains.

The thesis still stands, but this transition is taking longer than expected. A shift in the global demand-supply balance has resulted in milk being sold more cheaply on the international market than in China, prompting domestic processors to eschew local supplies for imported milk powder. The recent scandal surrounding the missing millions at Huishan Dairy is a sideshow, relevant only in that it shows how hype can obscure a litany of alleged sins. This is a story about what happens when investors pick the right idea but at the wrong time – and how they try to figure a way out.

"While dairy has a strong long-term future in China, the industry is in a state of flux," says Richard Field, a director at Orrani Consulting, who specializes in dairy. "Some of these companies have a simple business model – produce raw milk and sell it to a few major customers – but when prices are down, it's tough to sustain. There is a shakeout to come, which will see companies disappearing and diversifying, and a lot of M&A."

Bigger spenders

Chinese consumers are clearly spending more on dairy; the pertinent question is what exactly are they buying. While Euromonitor International's statistics indicate that sales of drinkable milk products have flatlined over the last four years – reaching RMB249.4 billion in 2016 – yogurt and sour milk product sales have doubled, coming in at RMB103.2 billion.

Even though there is increasing demand for high-end products that must be made with fresh milk, the mass-market stalwarts remain milk and yogurt-type products made through ultra-high temperature (UHT) processing. The emphasis is on long-dated expiry rather than premium taste, and so processors rely wholly or partially on milk powder. Products are often sold as liquids but have been reconstituted from powder – a common practice globally, although industry participants say that mislabeling and suspect marketing are rife in China.

This dynamic began to turn against domestic milk producers in March 2014 when the GDT Price Index, which tracks milk prices globally, fell from around 1,500 to below 800 in the space of six months. However, David Mahon, executive chairman of Mahon China, which has advised a range of dairy companies on country strategy, traces the origins back further to a dairy scandal that prompted stockpiling of milk powder.

"A lot of farmers were getting RMB5.50-6.00 a liter but suddenly the price dropped because processors had stockpiled so much milk powder," Mahon says. "To this day, there is probably more than 350,000 metric tons stored around China - way more than what is needed. On top of that, there was expansion in New Zealand and then the US and Europe started to export. Everyone was trying to go after the same market in China."

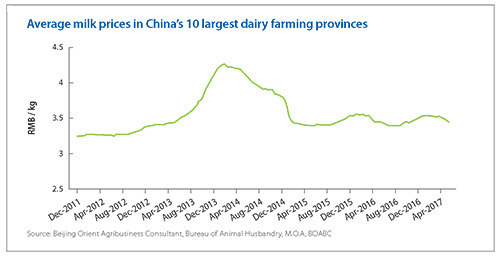

Modern Dairy noted in its most recent annual report that last year the total quantity of imported liquid milk and imported bulk milk powder in China reached 630,000 tons and 600,000 tons, respectively, an increase of 38% and 11%. According to domestic agribusiness consultancy BOABC, the average milk price in China's 10 largest dairy farming provinces slipped below RMB3.40 per kilogram in the middle of 2016. It surpassed RMB4.20 per kg in 2014.

Settle observes that New Zealand dairy farmers, thanks to their scale and efficiency, can generate a reasonable profit from prices of RMB2.70 per kg whereas many of their Chinese counterparts struggle to break even at RMB3-3.30 per kg. He knows of smaller players that have resorted to pouring milk down the drain because they can't sell it – "A recipe for very quick bankruptcy or closure" – while larger operators must deal with constrained profit margins.

Stick or twist?

"It's been up and down, up and down," says one investor with exposure to the space. "So much money went into dairy and there was massive expansion, massive oversupply. It's hard to take capacity out of the market because the cows are still producing milk. Eventually the demand-supply imbalance will correct itself, prices will go up, and people will make money again."

Others have already decided it's not worth the wait. In 2014, RRJ Capital committed $249 million for a 45% stake in Shanghai Bright Holstan, a farming joint venture with Shanghai-listed Bright Dairy & Food. The agreement was to work towards a listing in five years, and if that failed to happen, the private equity firm could sell all or part of its interest. RRJ appears to have negotiated an early release, with Bright Dairy buying its stake for principal cost plus 10%.

RRJ is not the only investor that went in with downside protection – typically a put option – but these arrangements are not uniform in terms or structure. The largest unrealized post-Modern Dairy deals include Affinity Equity Partners' purchase of a 40% stake in a farming joint venture with Beijing Capital Agribusiness Group (Sunlon) for $123 million and an alliance between PAG Asia Capital and Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial Group. The latter is listed while the former is not.

Yili's initial agreement, signed in June 2014, was with Yunfeng Capital and CITIC Private Equity. The two investors were supposed to put in at least RMB2 billion for a 60% stake in Inner Mongolia Livestock Development, but the deal didn't go through. PAG arrived in April 2015 with a similar sized check and extra conditions: Yili agreed to purchase all the joint venture's fresh dairy products and the JV in turn guaranteed Yili at least 70% of its production volume.

PAG – which has the right to ask Yili to buy back its stake at cost plus a small amount of upside after a certain period – was close to selling a 19% holding to the Chinese company's management team in January of last year. The plan was nixed due to capital market fluctuations.

Having a parent or associate company in the processing space can be helpful in securing long-term supply contracts. China Mengniu Dairy became Modern Dairy's offtake partner in 2008, but according to Barney Wu, a dairy industry analyst with Guotai Junan Securities, the processor took 60% of its partner's raw milk. Following Mengniu's acquisition of a majority stake in Modern Dairy earlier this year, its offtake share is expected to rise.

Nevertheless, Wu expresses puzzlement at the level of PE interest in dairy farming given how cautious strategic players have been about upstream assets in recent years. "Even Mengniu didn't appear comfortable holding a majority stake in Modern Dairy," he says. "Five months after the transaction, it tried to sell down its exposure in the company by issuing bonds that could be exchanged for shares of Modern Dairy."

A Modern tale

By the time the influx of capital – from private equity and other sources – had enabled farming businesses to build new infrastructure, buy cattle and start making a difference to industry production volumes, KKR and CDH had done well out of Modern Dairy. The 2008 investment was fully exited in September 2014, with a 2.9x return. The following July they sold out of a greenfield cattle farming joint venture established in conjunction with Modern Dairy in 2013.

However, the proceeds of the second transaction came in the form of HK$1.9 billion ($245 million) in Modern Dairy stock. This resulted in KKR and CDH exiting the company for a second time in January 2017, when Mengniu came in for its majority stake. (It had already bought a sizeable minority interest from KKR and CDH in 2013.) Just before the sale, the GPs were issued enough new shares to ensure they exited at roughly the same valuation they had entered.

This action was necessary because Modern Dairy's share price had fallen by about 50% over the previous 18 months. It reflected a difficult period commercially, culminating in the company issuing a profit warning in February ahead of announcing a net loss for 2016 of RMB785.5 million compared to a profit of RMB355.3 million the previous year.

Modern Dairy is China's largest raw milk producer, with 229,900 cows – half of them milking cows – across 26 farms as of December 2016, and 855,353 tons in total external sales. The company blamed its weak performance on low raw milk prices due to rising imports of liquid milk and milk powder as well as increased competition in the branded product market.

Nevertheless, Modern Dairy was cautiously optimistic. The size of the national dairy herd has decreased rapidly as the challenging commercial environment forces smaller players out of the market, and it is hoped this will help address the oversupply issue. International milk powder prices have also been rising, while domestic raw milk prices appear to have stabilized.

On a longer-term basis, policy trends are in the industry's favor. A national development plan published last December outlined four core principles: good grass plantations, high-quality cows, premium products, and integrated operations. The plan also set down a self-sufficiency ratio – at least 70% of all milk consumed in China must be sourced locally – and indicated that large-scale farms must account for no less than 70% of output by 2020.

Meanwhile, as Chinese households become more sophisticated, protein consumption will continue to rise. As such, demand for premium dairy products will grow. "Most milk is consumed locally – New Zealand is an anomaly – and history has shown us that as incomes go up, the proportion of dairy in the diet increases," says Settle. "In China, that's happening with the new generation. They've had milk in their diets, in various forms, since they were born."

For those private equity investors that bought in at the peak of the market, however, it remains to be seen how long it takes for prices to reach a point where they justify entry valuations. It is worth noting that the most successful investments in the space were made in 2008-2010 when the industry was reeling from a safety scandal and pricing was weak.

"There is demand for higher quality milk but that doesn't mean people will pay three times the price for it tomorrow," says one PE professional who invested in dairy at this time. "Our thesis was you can replace low-quality milk with high-quality milk at the same price through having efficient operations. You should be realistic in your pricing projections and not overpay, because it's not a sexy business, it's a damn farming business. You need to do everything right to get a 20% return."

Talent and timing

Proterra Investment Partners – a food and agriculture-focused GP that spun out from Black River Asset Management, the alternative investment arm of Cargill, in 2015 – took this approach with AustAsia, which it first backed in 2010 alongside Singapore's Japfa. They bought a rundown dairy farm, gutted it, and built a new facility from scratch. AustAsia now has around 65,000 cows, including over 35,000 milking cows, across multiple farms. It is generally acknowledged to be the leading large-scale dairy farm operator in China.

"Of the top 10 dairy farming operations in China, seven or more are probably losing money. But AustAsia is making money – it is on track for record EBITDA and net income this year. That's because the firm achieves average daily milk yield per cow of close to 40 liters. The China average is 15-17 liters and the other leading operators are probably in the low 30s at best," says Tai Lin, a managing director with Proterra.

Operational efficiency is therefore one way in which dairy farm operators can stop pricing pressure from eroding their profit margins. Various groups are exploring M&A options – essentially seeking efficiency through scale – and further consolidation is an inevitability. Mahon of Mahon China sees this as the quicker of two exit options for private equity investors: they can wait for international milk powder prices to fall and the domestic supply imbalance to right itself; or they can seek formal alliances with processors that want to become more diversified.

The sentiment is echoed by John Gu, head of private equity at KPMG China, who notes that China doesn't yet have a Fortune 500 company in the agriculture space. Mengniu won support from Cofco, the country's largest food processor, manufacturer and trader, when the industry was struggling after the 2008 safety scandal and the company remains acquisitive. "If you build something that has a value proposition you could easily become a target for a group like that," Gu says.

Settle, meanwhile, is going in the opposite direction. He plans to build an integrated farming business but on a smaller scale – catering to a niche, high-end market – and not overreach in a manner that proved costly to Huaxia. Whatever the model, timing the cycle is every bit as important as establishing a well-run operation. Charts that plot the development of dairy consumption in China might be littered with lines tracking in a steady upward direction, but milk prices themselves exhibit regular highs and lows. While a maturing industry tempers this volatility, it's a gradual process.

"Small players are getting out of the market and more institutional players are arriving," says Proterra's Lin. "When 99% of production came from small-scale farmers, they were in and out of the game. These swings happen. As an institutional investor, you are more likely to fund through the down-cycle, so you should see a bit more of a stubborn cycle now, than in the old days."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.