China cross-border VC: Home from home

Chinese capital is chasing deals in America’s technology space, but success in Silicon Valley requires a long-term commitment. Does the new breed of US-born Chinese VCs have the right cross-border strategy?

Amy Gu's resume was a good fit for Evernote: a computer engineering degree from Nanjing University, a MBA from Stanford, business strategy work for China Mobile and British Telecom, and founder of a few internet start-ups. For three years from 2011, she oversaw all aspects of Evernote's localization in China. Gu's team formed alliances with nearly 200 business partners and expanded the user base from zero to 15 million, making China the company's second-largest market globally.

She left Evernote with a view to repeating the trick with other US internet companies, initially as an angel investor. Last year, Gu went institutional, launching micro VC firm Hemi Ventures. She set out to raise a $10 million fund but ended up increasing the target to $50 million. LPs have already made commitments accounting for the bulk of the corpus. Most of the money comes from US and Chinese-listed companies in the technology sector as well as traditional industries.

"We have been lucky in terms of the timing – it's not easy for first-time fund managers to raise money," she says. "We only invest in US start-ups right now, and I want to concentrate on technology that China doesn't have. Given my operational experience of bridging the US and China markets, I would expect to help portfolio companies in this respect."

Hemi Ventures is part of a new generation of Chinese VCs that have established a presence in Silicon Valley over the last three years, supported by Chinese strategics and high net worth individuals (HNWIs). These firms distinguish themselves by promising to bring success to US start-ups domestically and also in China – but it takes time to cultivate the influence and reputation required to secure the best deal flow in a highly-competitive market.

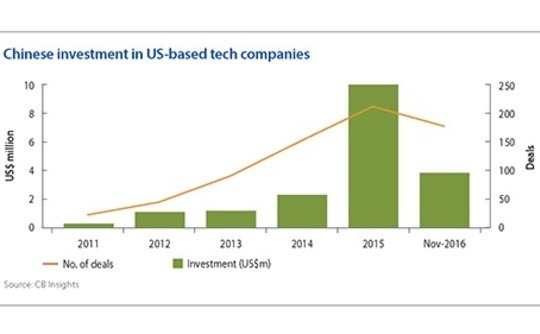

Chinese investment in the US technology sector has gathered pace over the past five years, peaking at nearly $10 billion in 2015, according to CB Insights. Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Sofi and Snap are the big names in a legion of start-ups that have received capital from investors ranging from Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings to traditional industry players such as hotel group Jinjiang International to private equity investors like Hillhouse Capital. However, activity slowed last year, reaching $3.8 billion as of November, due to Chinese currency controls and weaker sentiment in the US tech space.

Putting down roots

In 2005, Tencent became the first Chinese internet company to establish a beachhead in Silicon Valley, followed by Baidu and Alibaba. They were subsequently joined by second-tier players such as software developer Qihoo360 and online retailer JD.com. Since 2015, Chinese representation in the Bay Area has mushroomed, with groups as diverse as domestic PE firm Zhongzhi Capital, aviation conglomerate HNA Group and government-backed fund Westlake Ventures all opening offices.

Gopher Asset Management – a unit of Chinese wealth manager Noah Holdings – arrived last year. The firm has found success in giving Chinese HNWIs access to fund-of-funds and secondary funds underpinned by domestic assets. It is now building out an offshore program with a view to pumping hundreds of millions of dollars into US-based VC funds and direct venture deals. Gopher's Silicon Valley efforts are led by Elise Huang, who has been active in the area since the mid-1990s, working for Vertex Ventures and WestSummit Partners.

"The reasons for us to have an office in the US are twofold. First, it gives us a more proactive strategic understanding of global venture capital. Second, we are seeing a lot more inbound transactions from Silicon Valley, especially involving Chinese founders or VC-backed US companies that want to expand in Asia and particularly in China. Without a presence in the US, we cannot really evaluate and understand the credibility of these deals," says Piau-Voon Wang, co-CIO of Noah Holdings.

Similarities can be drawn between this trend and the way in which US-based venture capital firms expanded into China in the 1990s and early 2000s. Sequoia Capital, Lightspeed Venture Partners, Redpoint Ventures, KPCB and Walden International were among the pioneers, setting up local teams to make early bets on a technology sector that was unproven but rich in potential. They invested out of global funds, with the leading groups going on to raise dedicated China vehicles. An affiliation with a US firm made it easier to source capital from US LPs.

A US VC firm looking to crack the China market today would face more concerted domestic competition in the form of spin-outs from established players and GPs created by executives from successful local start-ups. For Chinese investors entering the US, the challenge is greater still. Silicon Valley is by far the most sophisticated and heavily contested technology ecosystem in the world.

"As a newcomer in Silicon Valley, it is very difficult to be successful if you don't have a clear investment focus," says Ying Wang, a managing director at Fosun Kinzon Capital, a VC arm of China's Fosun Group. "Unlike most of the established VC firms here, we're not a generalist fund. We focus on three strategic areas: financial technology, digital health, and pioneering technologies like big data and robotics. When we speak to US entrepreneurs about our resources in China and elsewhere, they are interested in us."

Fosun Kinzon also has a mandate to invest in US venture capital funds, but getting access can be difficult because many GPs are routinely oversubscribed and seldom feel the need to look beyond their longstanding US LPs. This is why Chinese corporates and financial investors also target start-ups directly.

"It's not easy, which is why the fact that Elise has been there for so long is important for us. We recognize that we have to prove ourselves, to work with GPs on certain deals, and demonstrate that we are able to help portfolio companies," says Noah's Wang." There are so many Chinese firms on the ground now, you need to establish your credibility. Money itself is not enough; you have to prove that you can add value."

Hard won returns

Even as a direct investor, though, securing a piece of the most sought-after deals, or taking the lead in funding rounds, is not easy. US venture capital firms have more than enough capital to meet the needs of these start-ups as well as deep experience in helping companies develop. GGV Capital has proved that it is possible to access strong deal flow in the US, but the firm is to a certain extent unique: it started in the US and then went to China, and built track records in both markets simultaneously.

Hans Tung joined GGV three years ago as a managing partner, moving from Beijing to Silicon Valley. While he was able to plug himself into the local founder community relatively quickly, building a reputation in a foreign country requires strategic thought. Tung believes his ability to spot potential in start-ups that have been turned down by traditional US VC firms – in part because there is an underappreciated China angle – is a key contributing factor.

"Wish and Poshmark are good examples. Because of my China experiences and insights – for example, placing a premium on mass market price points and social vitality of high-frequency apps – I was able to develop conviction and bet on them earlier than others would," says Tung. Once these companies had gained traction, US-based investors became interested.

Mobile shopping app Wish is a classic Sino-US start-up in that it connects sellers from Alibaba's Taobao and Tmall platforms with consumers in the US and Europe. However, such deals represent a tiny fraction of the US start-up landscape. If Chinese venture capital firms are going to get traction in the US, they must demonstrate an ability to help local founders achieve scale in the local market. Of Tung's 20-plus investments in the US, 90% of the founders are non-Chinese. It is a similar dynamic at Sinovation Ventures: locals set up almost all of the companies backed by the US team.

Crucially, GPs in this second category do not have a strong preference for backing companies with Chinese founders or with clear ambitions to expand in China. They tend to target early-stage science-driven technology start-ups in areas such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, where there is a reasonable expectation of adoption in multiple countries, including China.

"China is part of story because it differentiates us from other US VCs, but I don't think it's sufficient on its own to succeed in the US. We also have partners and potential customers for companies here in the US as well," says Shelley Zhuang, who worked for Draper Fisher Jurvetson in the US and China before setting up Eleven Two Capital three years ago. LPs in her $60 million debut fund include the founders of Alibaba, Tencent, Qihoo360, 21Vianet, and China Renaissance.

Lu Zhang, a 26-year-old founding and managing partner of NewGen, echoes this view, stressing that she is most interested in start-ups that have primarily domestic expansion strategies. Zhang set up medical device business Acetone while a science and engineering major at Stanford, sold it in 2012, and then became a venture partner at Fenox Venture Capital. She believes that her age and entrepreneur-turned-investor experience are helpful because the founder demographic is becoming younger.

"These bright young Chinese managers are working extremely hard to establish themselves in the Valley, which should make up for their relative lack of experience. The only worry I have is, from a continuity point of view, whether or not the same sources of capital behind their first funds will still be around when they raise their next funds," says Sinovation's Evdemon.

Cultivating an institutional LP base becomes a priority for these US-born Chinese VC firms from Fund II onwards. Amino Capital raised $4.4 million from 29 Chinese HNWIs for its debut vehicle in 2012 and then closed its second fund last year with $50 million in commitments from 80 entrepreneurs and tech executives, most of them China-based. Buoyed by exits from computer vision algorithm maker Orbeus and language-based predictive sales tools Contastic, the firm is now seeking $300 million for Fund III. It has received interests from fund-of-funds and family offices in the US, the Middle East and Hong Kong.

"We run a new model for cross-border investments. Sourcing deals in Silicon Valley, we can offer US companies a China strategy by recommending China general managers they can hire or public companies they can work with," says Sue Xu, a founding partner at Amino. "We have strong connections through our LPs – for example, Airbnb's new China head Hong Ge is one of our investors and also an advisor – who can help companies expand in China."

Early movers

It is important to note that Amino and its peers represent a new type of cross-border GP in that they do not have physical operations and investments in China. While firms like GGV and DCM Ventures are considered first generation because they run independently functioning teams in both markets, US-born Chinese VCs leverage their LPs to provide on-the-ground intelligence. This could result in introductions to Chinese corporates that are potential customers or manufacturing partners, offering a level of scale and revenue diversification unusual in start-ups.

"For the next generation of cross-border VCs, there could be a new model where the VC is a catalyst in helping US companies go to China at an early stage. I think many US tech companies failed in China, not because they didn't have the resources, but because they waited too long, and the market had already gone," says Jay Zhao, a partner at San Francisco-based Walden Venture Capital. "Also, many of them were reluctant to set up a separate local entity to share the economic upside with local teams, which can make you much less competitive in China."

Walden Venture Capital was one of the first to target Asia with the establishment of Walden International in the mid-1980s. The regional team spun out pre-2000 to form an independent partnership and raise its own capital. At present, the US business has no LPs from China, but it is considering raising capital from Chinese investors with a view to leveraging cross-border opportunities. This might involve helping a US e-commerce company to localize and build scale in China at a faster pace than in its domestic market.

"The competition between Uber and Didi Chuxing is an interesting case. Both companies spent billions of dollars in China, fighting for market share, but when they walked away from this costly battle Uber took some equity in Didi and Didi had some upside in Uber as well. Imagine if there were a cross-border VC firm to bring that about at the very beginning – it would save billions of dollars and a lot more value could be created," Zhao adds.

This hands-on approach requires a long-term commitment to the market, not the "venture tourism" that has been associated with a number of recent Chinese arrivals in Silicon Valley. There are also some established China-based firms – such as Morningside Venture Capital, Yunqi Partners, Banyan Capital, and Frees Fund – that dabble in the US. They might fly in a few times a year, attend start-up demo days and write a few checks, and also help portfolio companies with specific China needs. But if the US is to become a more meaningful part of their strategy, proven on-the-ground capabilities are required.

"There are a lot of investors that are newcomers to the Valley – and some of them might not have a clear strategy or goal. They are like ‘Oh, let's just invest,'" says Gu of Hemi Ventures. "Without a clear goal, they might lose a lot of money here."

Latest News

Asian GPs slow implementation of ESG policies - survey

Asia-based private equity firms are assigning more dedicated resources to environment, social, and governance (ESG) programmes, but policy changes have slowed in the past 12 months, in part due to concerns raised internally and by LPs, according to a...

Singapore fintech start-up LXA gets $10m seed round

New Enterprise Associates (NEA) has led a USD 10m seed round for Singapore’s LXA, a financial technology start-up launched by a former Asia senior executive at The Blackstone Group.

India's InCred announces $60m round, claims unicorn status

Indian non-bank lender InCred Financial Services said it has received INR 5bn (USD 60m) at a valuation of at least USD 1bn from unnamed investors including “a global private equity fund.”

Insight leads $50m round for Australia's Roller

Insight Partners has led a USD 50m round for Australia’s Roller, a venue management software provider specializing in family fun parks.